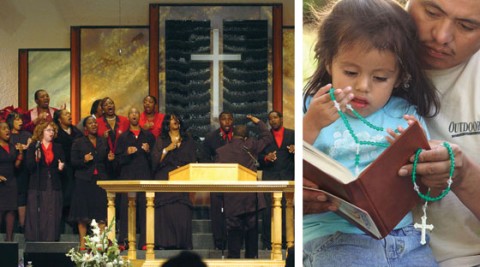

Diverse and devout

Ten years ago, in his much cited work Bowling Alone, Robert Putnam dramatized the collapse of civic engagement in the U.S. in the last third of the 20th century. Membership in associations of all sorts—the Boy Scouts, PTA, bowling leagues and, yes, churches—had declined since their heyday in the 1950s, he reported. All sorts of public and civic activities were fading: newspaper reading, attending political meetings, joining unions, giving blood, even going out to nightclubs. It seemed that we were in the midst of an irreversible process of social entropy. Putnam referred to it as a crisis of "social capital," with the nation losing the resources of all those interpersonal networks that greased the wheels of democracy.

Churches were only a part of the picture in Bowling Alone, and religion was not the heart of the problem. The decline in church networks had more secular than religious causes—especially the passing of the "great generation" that fought World War II. The conservative end of the Protestant spectrum provided a partial exception to the pattern of decline, but that, in turn, raised a deeper concern in Putnam's mind, for the evangelical and fundamentalist churches that were on the upswing did not appear to be a source of the kind of civic engagement, or social capital, that he as a political scientist was most interested in.

Putnam introduced an influential distinction between "bridging"

social capital, which is produced by civic-minded associations,

including most mainline Protestant churches, and "bonding" social

capital, which is produced by ethnic clubs and, he argued, conservative

Protestant churches. If an organization, whatever its ostensible

purposes, functions socially to promote solidarity among its members

and build a moat around them, no real benefit accrues to the store of

social capital in the wider society. By contrast, an association that

produces bridging social capital motivates its members to contribute

their selves, their time and their substance to the needs of the

society. The worry in Bowling Alone was that it was precisely

the churches that produce the most bridging capital that were on the

decline and the bonding ones that were flourishing.