A review of God’s Battalions and Fighting for the Cross

There was a time not long ago when Americans hurried home from work each evening to watch the news. For 30 minutes, they tuned in to the networks to learn what the president had done that day, to be updated on the latest global skirmish or natural disaster, and perhaps watch a human interest story and have a chuckle. Individuals might prefer the style of one particular anchor over another, and on occasion a network would scoop its rivals with an exclusive story, but the nightly news was strikingly similar from source to source and from station to station.

Today, the news no longer exists. One of the signature developments of the past decade has been the proliferation, compartmentalization and repackaging of information to fit the tastes of almost any consumer. News is not merely broadcast 24 hours a day. It is cast in radically different ways to appeal to distinct, targeted audiences. Conservative viewers tune in to Fox News for a confirmation of their judgments and perceptions, while liberals find a home—and a sympathetic spin on the events of the day—on MSNBC. The median age of a viewer of the CBS Evening News is now over 61, while 18-to-24-year-olds make Jon Stewart's The Daily Show their preferred broadcast source for current events. A growing number of young people do not get their news from television at all (let alone from newspapers), but follow breaking events—from the death of Michael Jackson to the earthquake in Haiti—by reading firsthand accounts posted by everyday individuals on Facebook, Twitter and other electronic sites.

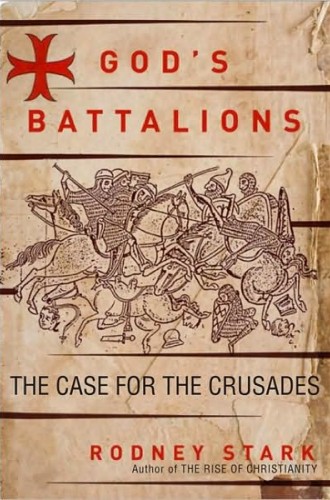

I couldn't help thinking of this seismic shift as I read two of the latest books on the Crusades, Rodney Stark's God's Battalions: The Case for the Crusades and Norman Housley's Fighting for the Cross: Crusading to the Holy Land. There clearly has been a marked rise of interest in the Crusades since the start of the present war in Iraq—an interest spurred at least in part by President George W. Bush's talk of an American crusade against terror in the days following the 9/11 attacks. Up to this point, the renaissance in publications about the Crusades largely has been limited to works that fit squarely within traditional historical scholarship. Christopher Tyerman's thousand-page history of the crusading period, God's War, and Thomas Asbridge's The First Crusade: A New History are just two examples. Stark and Housley, on the other hand, provide Crusades volumes for an age in which information is targeted to distinct and splintered interest groups.