Up

The sweet and thrilling Pixar animated feature Up is a paean to the possibilities that remain in a life shadowed by loss and disappointment. It’s about resurrecting buried dreams and using the judgment acquired over a lifetime to modify those dreams.

The first 20 minutes constitute a sentimental triumph. They encapsulate the relationship between Carl and Ellie, who meet as children (the young Carl and Ellie are voiced by Jeremy Leary and Elie Docter). The nervy, effervescent Ellie brings out the latent adventurer in the cautious Carl, and they dream of emulating their hero, Charles Muntz (Christopher Plummer), who claims to have located a prehistoric jungle in the South American wilds.

But in reality the couple ends up living quietly, and childless, serving as all in all to each other. Then Ellie dies, and pressure is put on Carl to sell his house to a developer. The memory of Ellie’s vision of life as an unending adventure sparks his resilience and rebelliousness. The film swings in an entirely unanticipated direction. Like the octogenarian played by Art Carney in Paul Mazursky’s classic comedy Harry and Tonto, the aging Carl (Ed Asner) uses the ending of one chapter of life to begin an odyssey.

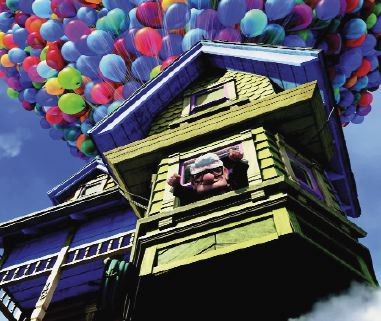

Carl’s journey is straight out of Jules Verne, with a variation that spins off of the end of the great children’s film The Red Balloon. Carl anchors the house he shared with Ellie to an immense bouquet of balloons and floats away to South America. In mid-flight he discovers a stowaway: Russell (Jordan Nagai), a boy from a Wilderness Explorer troop. To his astonishment, Carl gets in old age a taste of being a father.

The writers, Bob Peterson and director Pete Docter, keep shifting our expectations. The viewers don’t know any more than Carl does what twists and turns await him. When the house lands, the movie introduces an outsized avian creature—a cross between Big Bird and a peacock with a psychedelic plume and a comb like a tiara. Russell befriends him instantly and, with the oddball matter-of-factness of childhood, names him Kevin. Carl also meets a team of dogs that Muntz fitted with collars that permit them to speak.

Kevin is a charmer, but the film makers are at their most inspired in their handling of the dogs. The dog scenes have a Loony Tunes logic: the dogs’ communication skills have evolved but not their psychology; their dialogue is a witty and hilarious reflection of the way canines see the world. To them, all human beings are mail carriers (they refer to Russell as “the little mailman”). Even in the throes of a mission on behalf of their master, they’re continually distracted by squirrels.

When Carl meets the sweetest member of the canine crew, Dug (screenwriter Peterson), away from his pack, the dog expresses his instant and unquestioning affection for his newfound friend and latest master. Dug’s love for Carl allies him to Carl and Russell in their quest to protect Kevin and his offspring from the ambition of the now ruthless Muntz.

Docter, working with the production designer Ricky Nierva and a team of animation artists, has created a film that is magically lush, but with a dark side: when Muntz sets fire to the airborne house, the image of Carl, dazed by the loss of the property that has symbolized Ellie’s love, is silhouetted against a crimson-black sunset. The 3-D techniques enhance the film’s visual splendor without being too emphatic; as in Coraline, the effects are pleasingly muted.

The Pixar film WALL•E scored better with adults than it did with children—who were made restless and were perhaps baffled by the silent 40-minute opening section. Up splits the difference. It shows an aging widower and an awkward child who is in need of adult guidance meeting on middle ground, and it should allow different generations of moviegoers to do the same.