Barely making it

Soulful and tough in equal measure, The Pursuit of Happyness is the ideal movie for the Christmas season. It’s a triumph-of-the-spirit film in which the protagonist’s journey from poverty and occasional homelessness to solvency and the promise of a future is so thorny and obstacle-laden that you can’t imagine how he’s going to get there. And the moment of triumph, coming after so much heartbreak, is understated.

The director, Gabriele Muccino, is an Italian working for the first time in the U.S., and he doesn’t approach the material—the true story of stockbroker Chris Gardner, dramatized by Steven Conrad—in the usual Hollywood way. Muccino plays against the familiar rhythms; he keeps his foot firmly on the downbeat.

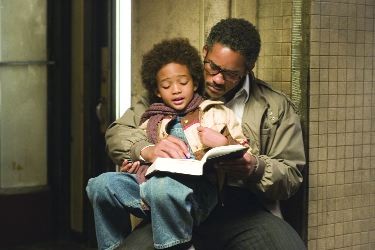

Muccino focuses on the star, Will Smith, who gives an eloquent, galvanizing performance as Gardner, a go-getter who’s optimistic, personable and brilliant, but luckless. He settles in San Francisco at the dawn of the Reagan era with a dream of selling enough bone-density scanners to take his wife, Linda (Thandie Newton), and young son, Christopher (played by Smith’s own son, Jaden Christopher Syre Smith), to a comfortable middle-class lifestyle.

But the product turns out to be too expensive and impractical. Though Gardner treks from clinic to doctor’s office every day, he has trouble unloading his supply. Meanwhile Linda works long hours as a chambermaid. Finally giving up hope that their lives will improve, she walks out. In just a handful of scenes, Newton gives a poignant demonstration of how misery can wear a person down to the very nub; she uses her lithe model’s body to suggest not airiness but disintegration.

After she leaves, things go from bad to worse. Gardner talks his way into a competitive internship at Dean Witter, but it’s a nonpaying post, so he has to keep hawking his scanners. A run of monstrous luck cleans out his bank account. He and his son are evicted. At his lowest ebb, he has to lock the scanners in a subway men’s room for the night.

The ironic title, derived from a misspelling of Thomas Jefferson’s words as they appear on the door of Christopher’s daycare center, suggests how complicated life is for those struggling to rise above poverty. The night before his interview at Dean Witter, Gardner is arrested for not paying parking tickets on a car that’s long since been impounded. He spends the night in jail in paint-splattered work clothes because he’d just been painting the walls of his apartment as part of a rent-extension agreement with his landlord. He’s released half an hour before the interview—too late to rush home and change. At one point he loses out on a spot at a homeless shelter because he has to pick up Christopher, and the line at the shelter is overlong by the time they arrive. It’s amazing that Gardner can keep up his energy and that his imagination stays sharp.

Muccino refuses to sentimentalize Gardner’s situation. We see how the daily battle to keep going brings out his edginess, as when he has to fight for a place on a city bus and to avoid being aced out at the shelter by a man who cuts the line.

We think of the 1980s in America as an era of prosperity, but the first image we see after a title announces “San Francisco, 1981” is of a homeless man. In its unstressed way, the movie addresses the disjunction between the way a man like Chris Gardner is forced to live and the perception of executives at Dean Witter that no one they’re likely to come in contact with could possibly be as financially stretched as Gardner is.

Gardner came of age in the 1970s, when a smart, industrious young man with a college education and exceptional people skills could still count on being able to build a life for himself and his family. The worst blows he takes are from the shock of realizing that his middle-class background, his talent and his tireless energy guarantee absolutely nothing.

That’s why Muccino and Smith present the moment when he wins a permanent job at Dean Witter as sober and bittersweet rather than ecstatic. The movie acknowledges the price of the long-sought prize and the fragility of success.