Arrested development

In director Todd Field’s Little Children, adapted from Tom Perrotta’s best-selling novel, Kate Winslet plays Sarah, an intelligent, expensively educated woman who is raising a preschool daughter in the suburbs. Her husband, Richard (Gregg Edelman), has apparently lost sexual interest in her; up in his study he amuses himself with photos of an Internet seductress known as Slutty Kay.

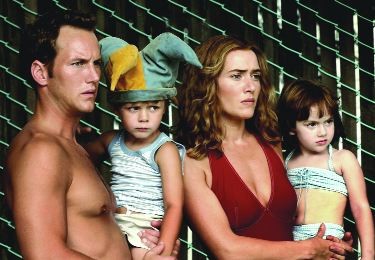

Sarah loves her daughter, but she fumbles with the challenges of motherhood. As the only mother at the park who forgets to pack her child’s morning snack, she’s regarded by her peers with a withering mix of disapproval and pity. When she meets an attractive stay-at-home dad named Brad (Patrick Wilson) with a little boy about her daughter’s age, she’s primed for a little summertime sexual experimentation.

So is Brad, though for different reasons. He loves his wife, Kathy (Jennifer Connelly), but he already feels like a wayward husband: he’s flunked the bar exam twice, and instead of holing up at the library to prepare for the next go-around, he’s been playing truant. He and Sarah fall into camaraderie, then into bed, and finally into a pipe-dream romance they foolishly believe will save their lives.

The title is ironic. Brad is lost somewhere in early adolescence, fixated on the bravado and expertise some local boys demonstrate in their daily skateboarding feats. When he’s recruited by a buddy (Noah Emmerich) to play football, he’s hungry to relive his glory days as a quarterback.

The movie juxtaposes the stunted Brad with Ronald McGorvey (Jackie Earle Haley), a paroled pedophile who’s moved in with his mother (Phyllis Somerville) in the same town and whose sexual proclivities are tied—way too neatly—to his inability to move past a childish dependence on her.

Sarah is also dealing with arrested-development issues, though this idea is clearer in the novel. And Brad’s football pal Larry, a cop forced into early retirement after he shot an unarmed teenager at a mall, behaves like a vicious bully with McGorvey because he’s unwilling to confront his own guilt.

Even in this abbreviated version of Perrotta’s narrative we get the point: deep down we’re all little children whose lives fall into crisis because we’ve been thrust into a grown-up world we aren’t prepared for.

But the movie never makes us feel any kinship to Sarah and Brad. A voice-over commentary reproduces sections of the book that describe the characters’ thoughts and feelings—a device that more imaginative adapters than Field and Perrotta (who co-wrote the script) would have rejected in favor of dialogue that dramatizes those interior lives. The filmmakers get away with it, though, by imposing a mocking tone that makes it sound as if they’re satirizing these paralyzed suburb dwellers. So the movie flatters its audience, in the style of American Beauty, by putting us in a position from which we can look down on the characters.

That decision doesn’t do much for the actors. Even superb performers like Winslet and Connelly are hard put to transcend the movie’s smug treatment of their roles. On the other hand, perhaps because he’s playing such an extreme character, Haley has a chance to burrow into the role of the pedophile, and his performance rises to almost operatic intensity in the late scenes.

This hate-letter-to-the-American-suburbs approach is gratuitous and fraudulent. It’s also distasteful, but perhaps less so than the foxy way Field shifts tone at midpoint to try to capture sympathy for characters he’s already made us feel superior to. The movie alters the ending of the novel to give the two least likely characters, McGorvey and Larry, a fairly baroque and extremely violent salvation, while restoring both Sarah and Brad to their marriages so as to affirm family values. We’re not supposed to remember that Richard is not the kind of mate Sarah might be happy to return to.

I’m not lobbying for greater fidelity to the book, which is no masterwork, but the changes that Field has made in the story reveal what the movie is: faux satire with a feel-good component.