A refugee’s fragmented memory

Viet Thanh Nguyen’s fractured and stirring memoir is haunted by war—and religion.

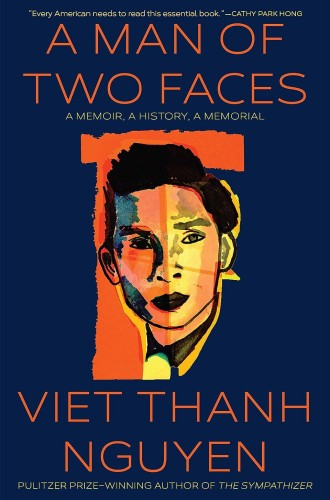

A Man of Two Faces

A Memoir, a History, a Memorial

In the provinces of the Philippines, my grandpa, a tenant farmer and peasant, is walking home when he is mugged by distant family members. They stab him multiple times, steal his money, and leave him to die.

When I try to remember how my father tells this story, I recollect the account differently each time. In one version it is midday; in another it is evening. Are they in the woods? Perhaps a stream of water flows by with a gentle and consistent hum? Does my grandpa fight back? I ask my dad to retell the story, yet each time I do, the peculiar details fall away before the ambiguous loss that echoes down generations. I reconstruct the story in my head, the truth of the event intact, with details lost to speculation.

It is this kind of fragmented memory that Viet Thanh Nguyen, Pulitzer Prize–winning author of the novel The Sympathizer, brings to A Man of Two Faces. Part memoir, part prose poetry, part social criticism, this book of refracted yet united forms retraces Nguyen’s life: from his birth in Buôn Mê Thuột, to life in a small house off a highway in San Jose, California, to a writing seminar with the esteemed and groundbreaking Asian American writer Maxine Hong Kingston, to the eve of his mother’s death as he stands near her and offers a final “I love you.”