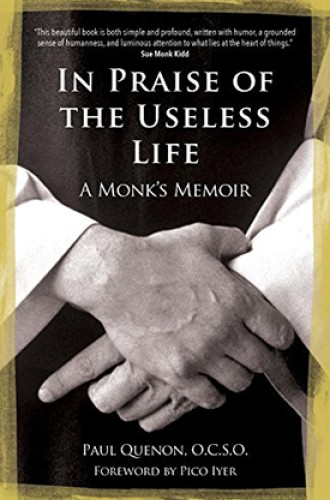

Monastic wisdom for a non-cloistered world

After 60 years at Gethsemani Abbey, Paul Quenon wrote a memoir.

“I am on permanent vacation,” says Paul Quenon, who then proceeds to define vacation not as an idyllic retirement lifestyle but as vacating, “an emptying out of the clutter within the mind and heart . . . to make room for God.” His 60-plus years as a monk, he says, have been “an interior journey into a wilderness to be alone, free of the world and at rest in God.”

In 1968, at age 17, Quenon visited the Abbey of Gethsemani in Kentucky and soon returned as a novice. He had read Thomas Merton’s The Seven Storey Mountain, but it was a month before he realized that the novice master, known as Fr. Louis, was the author. At 42, Merton was 25 years older than Quenon.

Although known for a nondirective style, Merton could be pointedly directive with the impatient and argumentative Quenon. At one point, Merton told Quenon that he was “narcissistic” and should “stop looking at himself” and simply live the life at the monastery. As Quenon matured, he intentionally cultivated freedom from self-absorption, intuiting that Merton shared a similar struggle. The two men became friends, and Quenon shares insightful and entertaining anecdotes of Fr. Louis as Gethsemani brother and spiritual leader.