Da Vinci was many things, but not a productivity guru

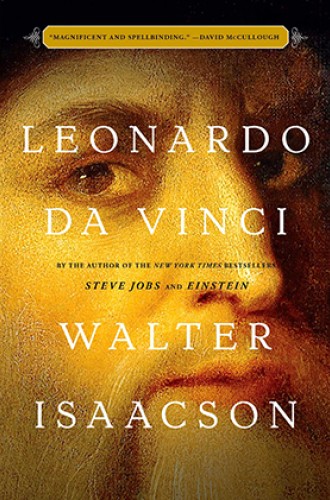

Walter Isaacson offers a clear and enjoyable biography. He also offers life hacks from Leonardo.

As a literary genre, biography seems straightforward: it offers the available facts about an individual’s work, victories, defeats, relationships, and more. At its best biography allows readers to get as close as possible to knowing a person without ever coming into actual contact with him or her. Walter Isaacson’s hefty new biography of Leonardo da Vinci gives us a good idea of how the artist and thinker presented himself in his notebooks, how he navigated the knotty world of patronage and politics, how he transformed artistic practice and unraveled scientific problems, and what he may have been like as a person. But Isaacson’s method of doing so raises questions about what motivates the writing and reading of a biography.

It’s not that Leonardo da Vinci is incomplete in any way. I can’t imagine a reader coming away from this beautifully illustrated, 600-page volume feeling cheated out of essential information, either about Leonardo himself or about his time, the places he lived, his circle of friends, colleagues, and patrons, or his newly rediscovered works, such as Salvator Mundi or La Bella Principessa. Nor does Isaacson rebel against standard form or style; the book is a plainspoken presentation, mostly in chronological order, of the life and work of the 15th- and 16th-century artist and thinker. Leonardo is a clear, generally enjoyable read that, in addition to painting a picture of the master’s interdisciplinary work and thought, emphasizes the importance of not pitting the arts and sciences against each other.

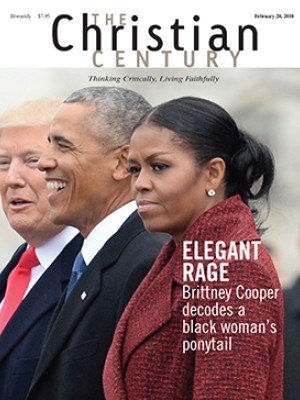

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

I eventually grew uncomfortable, however, with Isaacson’s periodic admonitions “to be more like Leonardo”—to stop and smell the proverbial roses just because they’re there, or to marvel at dust motes in sunbeams and the workings of a lowly cogwheel. And most readers probably do need a reminder to slow down and notice the world.

But Isaacson’s repeated counsels start to sound hollow next to his lamentations that the artist wasn’t very good at following through on proposals, publishing his writing, or finishing the projects he’d started. Although the author asserts more than once that all of Leonardo’s doodling and procrastination, and his apparently lowbrow theatrical work, was anything but a waste of time, he also expresses regret that the unflagging keeper of notebooks just couldn’t be bothered to publish what he wrote down.

That regret may be due simply to the author’s plain hunger for more Leonardo material, which Isaacson could have used to shore up some of his speculations about what Leonardo was really thinking when he drew swirling waters or chose to make use of a certain technique in a painting. But that lament may also say something about our productivity-worshiping culture that wants tangible results. It’s unsurprising, then, that Isaacson seems to want to put Leonardo in the same category as the very disciplined Steve Jobs, another of the author’s past subjects. In making periodic allusions and comparisons to the founder of Apple, Isaacson even employs Jobs’s advertising phrase, “think different.”

My discomfort came to a head in a concluding section, “Learning from Leonardo.” It seemed as if I’d been plopped down into a long LinkedIn article, with more than the usual five essential recommendations for changing your habits and attitudes in order to excel at your job.

There are, of course, many reasons for reading and writing about any topic, famous people included. Making sense of oneself and the world, or even “becoming a better person” because of either or both of those activities, is nothing to sneer at. But I’m not sure what it says, or how concerned we should be, when ultimately we’re encouraged to approach chronicles of the great and famous as sources of life hacks.