In Martin Marty’s classroom

One evening, Marty had the whole class out to his house. There were shelves of books that he wrote or edited and even more books by his students. I thought, I do not belong here.

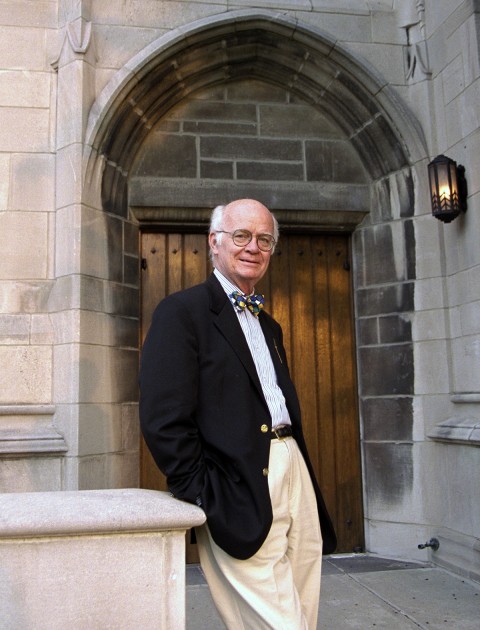

Martin E. Marty (Photo by Micah Marty)

The first time I remember hearing his name was in 1987. A colleague of mine asked whether I had chosen a seminary, and I told him I was going to the University of Chicago.

“Isn’t that where Martin Marty is?”

“Uh, yeah, I think so.” Had I heard the name before? I wasn’t sure.