Learning to see the planet as gift

At Holden Village, a Lutheran retreat center nestled deep in the Cascades, I asked my students to consider their vocation in light of the Anthropocene.

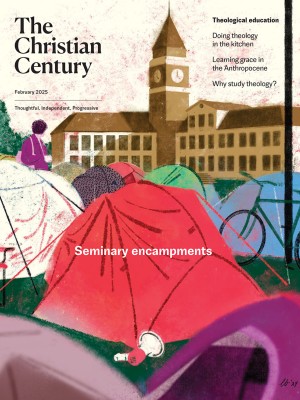

Holden Village, a Lutheran retreat center in the mountains of Washington State (Photo by Benjamin Stewart)

I’ve returned to Holden Village with our campus pastor and 17 college students. They still look a bit tired after our 44-hour trip—by train from Chicago to central Washington, then by bus following the Columbia River, then by boat up Lake Chelan (where students lost cell service for the next three weeks), and then by a school bus named Jubilee up 2,000 feet and around nine switchbacks before disembarking into this remote Lutheran retreat center and intentional community, nestled deep in the Upper Cascades. Tired, yes, but also eager—here on our first day of class, sitting in a circle of quilt-donned captain chairs in the fireside room.

The course is called “Creator, Creation, and Calling.” Before the month ends, students will discuss books on eco-theology and write liturgical prayers for the healing of ecosystems. They’ll tour the hydroelectric plant and hoist garbage cans full of food scraps into Thelma and Louise, two gigantic cylinder compost bins, during their garbology shifts. They’ll also reflect on who they are and the work to which they feel called—especially now, in the Anthropocene, this geological age of human-induced climate change and ecological degradation. Although the syllabus doesn’t put it this way, I’ve come to think that the primary learning goal for the course is to see and treat our planet as gift, a gift that elicits not only gratitude but also the discipleship of care, attention, and giving back what we can to the earth.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Gift is something of a controlling metaphor for the village’s self-understanding. Surprising Gift, Charles Lutz’s 1987 book about Holden, is still placed in every guest room like a Gideon Bible. It begins by recounting how the Howe Sound Mining Company gifted the deserted village to the Lutheran Bible Institute in Seattle after copper prices fell and the mine closed in the 1950s. It notes that life in the village is made possible by gifts of labor by countless volunteers. Lutz then names the capital-g Gift making these other gifts possible—“the Gospel, the story of divine giving, unearned and unconditional, to humankind.”

To trace human work through gratitude to grace is pretty standard Lutheran fare. Many at Holden, including students in my course, add a critical third piece: the gift of God’s creation and in return our care for this gift, otherwise known as environmentalism. It’s as though any gratitude for God’s grace without some measure of the giftedness of creation and the willingness to give back risks becoming cheap grace—grace as license and latitude. Costly grace, by contrast, entails living “intimately and sympathetically with the earth, [seeing] that we are surrounded and sustained by gifts on every side,” according to eco-theologian Norman Wirzba. The only proper response “to this unfathomable kindness,” he writes, is “working with the earth and making oneself vulnerable to its mysterious ways.”

It may seem as though Wirzba is only cherry-picking slogans from Dietrich Bonhoeffer when making his point about the cheap grace presupposed by our industrial agriculture and monetary economics and the costly grace that characterizes God’s creation and that evokes our attention and care. But we need ecological and other accounts of gift economies in order to properly value divine grace. Following Marcel Mauss’s original anthropological study of gift-giving in ancient societies, recent accounts of gift exchange by Lewis Hyde and Charles Eisenstein emphasize that a gift means much more than simply a commodity given for free. Indeed, focusing on the fact that gifts don’t cost anything (for the receiver) frames the gift within monetary economics, essentially equating a free gift with the price point of zero.

Bonhoeffer too critiques Lutherans and other Christians for devaluing grace, for thinking that it doesn’t cost anything and so is worth the same. In other words, we have confused the gift of grace with grace that costs nothing and so asks nothing of us. The way forward is not to better balance God’s free gift with the need for human work. Rather we need a better accounting and a different logic—one that values grace as gift and so sees it issuing in a different circulation, one distributed infinitely but without transactions. Bonhoeffer thus says about grace and discipleship what Lewis Hyde in The Gift says about gifts and the “labor of gratitude” that passes them forward: “A gift that has the power to change us awakens a part of the soul. . . . We submit ourselves to the labor of becoming like the gift. Giving a return gift is the final act in the labor of gratitude, and it is true acceptance of the original gift.”

Such retrievals of a grace that is free but not cheap thus returns one to the cost of discipleship, as the older translation of Bonhoeffer’s Nachfolge (discipleship) has it. Christian discipleship is a discipline—the conscious and practiced giving of oneself over and back to that which gives one life. What eco-theologians now add is that, yes, every good and perfect gift comes from the Creator, but always and necessarily through creation. It follows that receiving grace returns one to the ways of earth—which is nothing but a planet-sized gift exchange. We cannot “follow after” (nach-folge) God’s grace in the world without working with the grain of the earth—with carbon and water cycles and the laws of thermodynamics, with the topsoil and creatures whose gifts make human life possible. To believe in God or even loudly announce gratitude for grace without participating in God’s gift economy is to cheapen both and, in Wirzba’s words, to “deprive ourselves of an appreciation for the costliness of God’s good gifts, if we see them as gifts at all.”

In his poem “Work, Gratitude, Prayer,” Wendell Berry tells us to “Be thankful and repay / Growth with good work and care.” The poem ends with a warning about cheap grace and bad faith: “No gratitude atones / For bad use or too much.”

Back in the fireside room for the second day of class, Pastor Melinda begins our “centering time” with a voice recording of the Potawatomi botanist Robin Wall Kimmerer, who reads the story of Skywoman, an Indigenous account of creation, from her popular book Braiding Sweetgrass. Turtle Island is cocreated by Skywoman, who joins her own gratitude to the gifts offered by geese, otters, sturgeons, and a muskrat who gives his life diving to the bottom of the ocean in search of mud. Skywoman also brings gifts of her own: saplings to be planted in the mud, from which the dry land flourishes.

Kimmerer underscores the difference between this account of creation and those recorded in Genesis, contrasting Skywoman with another story of a woman in a garden with a tree. The first is “our ancestral gardener” and “cocreator of the good green world that would be the home of her descendants.” The latter ends up in exile after breaking a mandate from God. Her time on Turtle Island, according to Kimmerer, is “just passing through an alien world on a rough road to her real home in heaven.”

Gift is something of a controlling metaphor for Holden’s self-understanding.

These differences are important. They mark the distance that Christians and other monotheists must travel to honor and cherish the gifted bearers of other gifts, even as they give primary praise to the Giver. But because I want students to reread the Christian accounts with a second naïveté and to see what they might mean in our ecological age, I ask them to consider a subsequent chapter from Braiding Sweetgrass, “The Gift of Strawberries,” alongside the Genesis creation accounts. Kimmerer begins that exquisite chapter with stories of picking wild strawberries as a child, learning to patiently receive and cherish those gifts as they ripen slowly in the spring, regifting them with generosity and love when she and her sisters make strawberry shortcake for their father’s birthday. She also tells a series of what my tradition calls fall stories—stories in which the free gifts of the earth get made into private property through the enclosure of the commons, then commoditized and so made scarce and thus able to be sold.

Among these falls is a story of redemption—a return from enclosure and extraction to the extravagance of free gift. Kimmerer dreams of being back at a farmer’s market in the Andes that she used to frequent, except that in the dream, “gratitude was the only currency accepted.” Interestingly, the very profligacy of gifts given for free disciplines her into restraint. Her basket still half empty, but feeling full, she decides to forgo going over to the cheese stall, knowing that it would be given for free. “It’s funny,” writes Kimmerer. “Had all the things in the market merely been a very low price, I probably would have scooped up as much as I could. But when everything became a gift, I felt self-restraint.” She makes plans to come back with return gifts tomorrow.

One student would later tell me that the dream came to mind each time she checked email on Holden’s one shared computer in the library: “Having email access was nice, but I didn’t want to take more than my share of the village computer, so I was usually just on for a minute.” I thought of it again later at the ABC (anything-but-cash) market one Saturday afternoon in the dining hall. Contemplating trading one of my vouchers for a garbology or dish duty shift, I thought the homemade pottery mug—lopsided though it was—was too good of a deal. “Please,” the novice potter said. “I really don’t want to do dishes tomorrow.”

The students need some nudging, but they do put their fingers on details in Genesis 2 that take on a different meaning when read beside “The Gift of Strawberries.” Perhaps the permission to freely eat from any tree in the garden minus one means more than permission to consume without paying. Perhaps it’s a different way of eating—one that savors the gift, feels grateful and full, and so doesn’t want or need more.

Perhaps then the commandment not to eat of that other tree is simply a rephrasing of the invitation to freely eat every other. It makes explicit the necessary limit of gift as gift. (We talk of infinite growth of our monetary economy, but gifts only “grow” through the law of return. That growth ends—and gifts cease to be gifts—when they are taken out of circulation by extracting without regifting.) The no—the “do not eat”—seems but the vanishing point, the necessary limit, of the generous gift. Or again: to truly eat of gifts freely and gratefully has limit and restraint built into it, as Kimmerer’s dream suggests. Take a gift as a possession or right and it turns into not even that.

The students notice too that nonhuman animals are formed in the same way that Adam is formed—from adamah, or humus-rich topsoil, that from which the adam, the human, gets its name (Gen. 2:19, 7). Indeed it is out of that same soil that God “made to grow every tree that is pleasant to the sight and good for food” (2:9). In Genesis 1, even after God so dangerously singles out humanity to subdue the earth and have dominion over other creatures (1:28), God gives every plant yielding seed not only to these human beings, but to every other animal as well—to all who have “the breath of life” (1:30).

Read with these details in mind, it’s not a stretch to wonder whether the forbidden tree is forbidden to humans but offered to others to freely eat. Could the commandment not to eat simply ensure that animals have enough? At the very least, the divine command is not just an arbitrary rule, as if “no skipping on Tuesdays” would have sufficed. It’s about the gift of food and the prohibition against “bad use or too much,” as Berry’s poem puts it. Gratitude and restraint depend on each other.

Some students find these interpretations to be a stretch. I don’t blame them. Since Lynn White’s 1967 essay “The Historical Roots of Our Ecological Crisis,” many of us concerned with human-caused environmental degradation are accustomed to critiquing the patriarchal, colonialist, earth-subduing tradition called Christianity. Some forgo religion altogether; others look to Indigenous or Eastern traditions as greener options.

But as Hebrew Bible scholar Timothy Beal—author of When Time Is Short: Finding Our Way in the Anthropocene—reminds us, the biblical creation accounts were first told and heard by Indigenous people, sometimes as resistance to empire. If we mistake them for the ideology of the status quo, that is because we—on this side of Babylon, Rome, and settler colonialism—have forgotten how to read them indigenously. Relearning to do so makes us realize just how small the dominionist strand of the Bible is, even if Francis Bacon and other proponents of our emerging technocracy leveraged it in their quest to be like God. We realize, too, how often and emphatically scripture roots human beings in the humus shared by all who have life. The Bible’s “creaturely theology,” as Beal calls it, is primary. We simply need to learn to become the humus beings that we are.

At our last class session, Pastor Melinda asked students to consider what eco-spiritual practices they would take back home.

It’s the night before our departure, when we will take Jubilee down to Lake Chelan, board the boat, brace ourselves for the three weeks’ worth of texts that will commandeer our phones once we have cell service, and then head east by train to the “real world.” A 69-year-old named John gives a farewell acoustic guitar concert tonight in the art studio, singing about trains a’leaving and heartbreak and hope. He’s been at Holden this month volunteering as a floater—helping with snow removal, restoring porches, doing anything else the village might need. He recently went through a second divorce after the daughter of his spouse died by suicide and they couldn’t figure out a way forward together. He says that the ability to be OK with not being OK here at Holden is a gift. Students one-third his age speak of him in the same terms.

At the end of our last class session in the fireside room, Pastor Melinda asked students to consider what eco-spiritual practices they would take back home. Many spoke of ascetic practices, of things they would have to give up. Some planned to take media fasts once a week. Others would drive less. Still others would eat less meat. But for every no there was also a joyous yes—gratitude for gifts they wanted to cherish. They won’t scroll on their screens, and they’ll go outside with friends. They won’t drive, and they’ll go for walks. They won’t consume factory-farmed beef, and they’ll enjoy what they are eating—and that will deepen their gratitude.

For some of us, renouncing what is not freely offered, the discipline of not taking too much and not using it without returning it, will cultivate gratitude for all that remains. For others, gratitude for gifts will come first, redoubling as restraint. In either case, Christian discipleship in the Anthropocene has a cost, because gifts must be cherished and passed along. But that cost is nothing but the debt of gratitude that follows from life as an utter gift.