When climate is a tool of empire

David Livingstone explores the dubious history of overclaiming or distorting the role of climate.

The Empire of Climate

A History of an Idea

When Mississippi seceded from the Union in 1861, its Declaration of the Immediate Causes proclaimed the absolute necessity of slavery, which produced the goods necessary to the world’s commerce and civilization: “These products are peculiar to the climate verging on the tropical regions, and by an imperious law of nature, none but the Black race can bear exposure to the tropical sun.” The determinist and reductionist character of such a statement represents a long-standing theme in intellectual history, and by no means only in the West. That tradition forms the theme of David Livingstone’s deeply impressive and wide-ranging study The Empire of Climate.

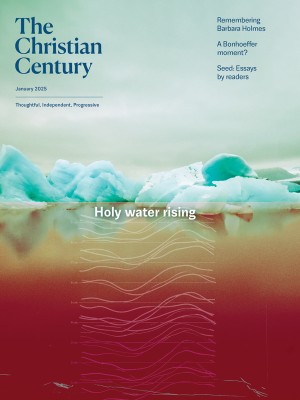

Livingstone takes his title from a 1748 statement by the philosopher Montesquieu that the “empire of the climate is the first, the most powerful of all empires.” Since ancient times, countless scholars had invoked climate factors to explain all manner of human qualities as they affected human health, the prosperity of particular societies, and the making of national character. Some of these linkages were simply loopy, but often—as in the case for the naturalness of enslaving Africans—they were profoundly dangerous.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

What makes Livingstone’s book so significant is that he traces this history up to the present day, showing how potent such determinism remains. Arguably, belief in the “imperious law of nature” is becoming even more widespread. The more concerned we (very reasonably) become about climate threats, the more we study their likely impacts, and we naturally tend to paint them in the most alarming colors. A scholar pitching a research proposal or a trade book on climate change is exceedingly unlikely to minimize the consequences for global futures.

In an ideal world, any such scholar would be required to read The Empire of Climate before proceeding with their project. Yes, of course they should study what is often called our climate crisis—but they should also learn about the long and often disreputable history of overclaiming or distorting the role of climate factors.

Livingstone approaches his topic from four angles: health, wealth, mind, and war. The relationship between weather and illness can be traced at least to Hippocrates in the fourth century BC, and it regularly featured in subsequent medical writings in the West. That is reasonably well known, but Livingstone also offers a sobering account of the modern history of biometeorology and its linkage to eugenics.

While there is reputable literature relating climate to development and prosperity, Livingstone also shows how often climate determinism has been used to justify colonial and imperial ventures. The racial implications are pervasive. Assertions of the natural inferiority of residents of the tropics, for instance, had appalling consequences in the era of transatlantic slavery, and vestigial versions of that theory survive into modern times. Livingstone demonstrates how, according to the worst stereotypes, the tropics have long been associated with disease, systemic poverty, mass violence, fanaticism, and state failure—not to mention indolence and sexual irresponsibility. How very different (at least in stereotypes) is the calm world of the temperate north, with its peaceful, enterprising, and hardworking citizens—cool people in every sense. And if nature and geography have so distributed the world’s populations, those features must be inescapable, if not eternally valid. All is determined: Why struggle?

The Empire of Climate is an excellent and timely book, and anyone working in climate-related areas should know its arguments. That does not mean that we have to agree with it on every point. Climate is not a one-size-fits-all explanation of human affairs, but neither is it irrelevant. At many points, a reader may nod in agreement with Livingstone’s general points about the evils of overclaiming, but that same reader must then ask whether Livingstone is denying any and all possible impacts. Does one size really fit nothing?

A very large body of sober and respectable scholarship stresses the importance of tropical diseases and parasites in limiting the economic growth of many tropical areas, at least until very modern times. Those factors determined the fate of empires. During the times of imperial rule in Africa, the lethal prevalence of such diseases made most of the continent inaccessible to European settlement (with the exception of some areas of the far north and south, and some highland areas in Kenya and elsewhere). That distribution had nothing to do with White European prejudices or pseudoscience; it was simply observed reality.

Livingstone also is very skeptical of much recent climate history, in which a great many scholars connect climate change to episodes of social or political crisis, or to outbreaks of religious dissidence or witch-

hunting. I am biased in such matters, as those linkages form the theme of my 2021 book, Climate, Catastrophe, and Faith. But I would argue that in many instances, such connections are now amply documented to the point of being undeniable. Climate, after all, is absolutely decisive in shaping such crucial matters as food supplies and patterns of epidemic disease, and waves of famine and plague had the power to devastate early modern societies. That is especially true if we look not at broad periods such as the Little Ice Age but at short eras of truly acute climate stress such as the 1320s or 1640s.

In modern times, the argument that climate stress will drive war and state failure seems indisputable. Although Livingstone challenges the evidence, he does so unconvincingly. If he does a splendid job of warning us against overclaiming, at times he comes close to rejecting the actual significance of climate. Despite that criticism, The Empire of Climate is essential reading. It is a stunning achievement.