The Christmas of Baby Tommy

We raised our kids without a religious narrative. My young son stumbled upon one on his own.

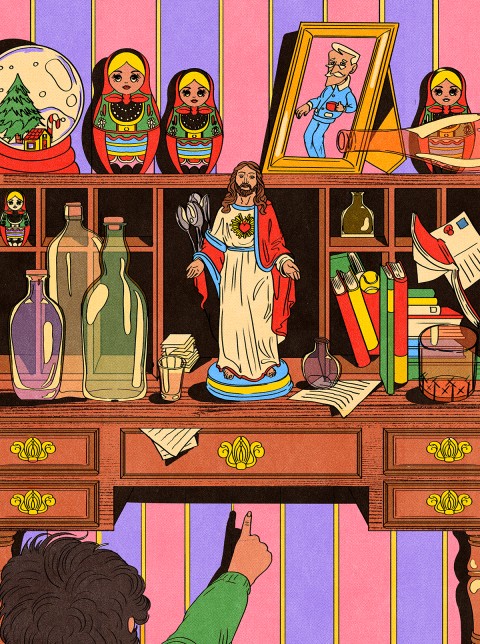

(Illustration by María Jesús Contreras)

In the last week before winter holidays, my son and daughter watch at least one movie a day in elementary school. Phonics and multiplication tables fade in the flickering light of The Polar Express and The Grinch. My kids are separated by two grades and literacy, but their viewing material is the same. This holiday school experience could not be more different than my own, growing up Irish Catholic. We spent Advent in candlelight and clouds of frankincense, focusing on the need to cleanse our souls in preparation for . . . something.

When my partner and I decided to have kids, we were vague and undeclared about most aspects of parenting, but we agreed we would not raise our kids in a particular faith, since we, as adults, didn’t have one ourselves. For my British partner, church meant dry fruitcake and honking organ music; for me, it meant an institution rigged for misery. It was settled: no baptism, no nothing. When asked questions (Why does that man have a black cross on his forehead? Why is that woman wearing a scarf over her face?), we would answer with what we hoped were even, open-minded, factual responses, as though our kids were conducting field surveys. We would be their anthropological guides.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

We had practice: my partner and I spent years studying religious art and literature in graduate school. I was proud to be called a “soulless Marxist” after delivering a conference paper on the economics of craft guilds and religion in the Middle Ages. I had severed the emotional from the intellectual with great success. I was an adult.

Though neither of us works in those fields any longer, markers of them fill our house. We have shelves of books on Byzantine icons and Corpus Christi plays and mementos gathered from research trips to the Vatican and Hagia Sophia and kitsch statues of Jesus and Mary. Our kids never remarked on these things. Not until the Christmas they were in kindergarten and second grade.

With the December scholastic film festival concluded, my kids were home for break and my parents came to visit. On Christmas Day we sat down to an early lunch so we could spend the rest of the afternoon snoozing off our wild boar and côtes du rhône comas. My father, a month from 70, never had much patience waiting to start eating at family meals, and all of us had taken bets earlier on how soon he would dive in that day. Not this Christmas. Not only did he wait for everyone to sit down, but after we did, when usually he would tuck into his mashed potatoes as we unfolded napkins, he turned to my five-year-old son and asked, “Do you know whose birthday we celebrate today?”

I wriggled in my seat. My father had no problem with our religious abstention, but then again he never knew the full extent of it, how what we really practiced was religious absence. I felt a sudden, deep inadequacy, and I expected my son to respond with an embarrassed shrug that I would need to explain.

To my surprise, he nodded. “Yup,” he said, and picked up a roll.

It was possible that he’d pieced the religious story of Christmas together but not likely. We’d never set foot in a church, and though we’d watched numerous Christmas films—as he certainly had in school—they all portrayed the holiday as one of snow, togetherness, elves, and sparkly tree ornaments. The closest religious exposure our kids received was from their babysitter, who taught them how to play dreidel, which they saw as a gambling game with interesting words and letters. None of their friends went to church or practiced any religion. We lived in an atheistic vacuum.

My father still hadn’t begun to eat, a miracle in itself. “Well, whose? Whose birthday?” he persisted.

My son pointed to the corner of the dining room, to the top of an old desk we use as a liquor cabinet. “His,” he said.

We all turned to consider the options: a set of nesting dolls of Russian leaders my partner got in Moscow in the early ’90s, a potted succulent, and a small ceramic statue of Jesus we normally used to hold teaspoons. I had moved Jesus to the desk as a holiday decorating effort, since his robe and burning sacred heart were red.

Jesus! He had to mean Jesus. My partner and I exchanged well-what-do-you-know glances. But in his eyes I saw my own concern that someone had indoctrinated our child without our consent. At my kids’ public school, outside visitors came to their classes all the time: a zookeeper with animals, a book illustrator with storyboards. Had one of these people been a covert proselytizer? Used the hedgehogs and dwarf rabbits to lecture the class about creationism? I wondered how many times a child would need to see a picture of Jesus to identify him, how many times he would need to hear the Christian narrative of Christmas to link the face to the holiday. We had been late to my son’s spiritual initiation, and it felt strange and wrong.

But my father was delighted. His grandson had positively identified the son of God. Hallelujah!

“And what’s his name?” my father asked, as my son stuffed his mouth with bread. I looked at my daughter, who often had trouble letting her brother answer questions before her. She liked to get there first. But this time she looked to him for illumination.

My son swallowed his bread, and said, matter-of-factly, “Baby Tommy. Today is Baby Tommy’s birthday.”

Relief and confusion duked it out in my head. Who the hell was Baby Tommy?

All of us adults at the table winced and let escape an uncomfortable chuckle. My dad started to eat. I stood up and reached for the Jesus statue, just to be sure.

“This guy?”

“Yeah, Baby Tommy, that’s what I said. Is there more bread?”

No one corrected him. My son’s voice was firm with conviction, and besides, if he was in a defiant mood, the challenge was not worth the effort. One recurrent dispute we had was about the word tomorrow, which he insisted was called “the day after today.” He even speaks in biblical terms, I thought. In no time he’ll start using “begat.” I should have seen it coming.

My son crossed the church threshold, filling me with dread. My atheistic parenting would be exposed—on Christmas Day.

When I visited my grandmother as a child, the only things to do were read her dictionary of medical ailments, watch geese shit on the lawn, or marvel at her morning screwdriver consumption. We usually opted for the dictionary as the chosen entertainment, and our all-time favorite entry was something called “hairy tongue.” We never read the description; the photo of the cotton-candy pink tongue pelted with coarse, black hair was sufficiently informative. Hairy tongue became a notorious, fictive family condition, and our parents joined us in ribbing each other about stray hairs on our lips, how Great-Aunt Gertrude surely, based on the sour pout of her mouth in the framed photos in Nana’s house, was the first of the hairy-tongued ancestors. Making stories, myths of our surroundings, was better than watching defecating geese any day. It wasn’t any different for my grandmother.

Vodka-soaked by 10 a.m., she’d pull out a canvas painted in muddy oil colors, a portrait of a stunning young woman, cheekbones you could fold paper on. “You know we’re related to the Hepburns, don’t you—as in Katharine Hepburn?” she’d say, and from there begin her exegesis on the grafting of the family trees, which ended with a comparison of her own bone structure to that of the woman in the painting. We never knew who the woman was, maybe Hepburn’s fourth cousin twice removed, but Nana pointed to her as proof of all her conjectures. Over the years my grandmother shared other family stories with us: her sister was painted by Diego Rivera on a church wall in Mexico City; as a child, she had a pet monkey. All of these things could have been true, and we believed them, as much as we believed we might one day wake up with hairy tongue. A child doesn’t need much proof to corroborate the words of an adult, booze-slurred or not.

Nana’s stories were preferable to what my brother and I heard in Catholic school. I don’t remember parables about brotherly love or charity. I do remember my brother’s math teacher repeatedly threatened to stitch his hands in his pockets should she see them there. I saw her hiss this warning once, her words glinting like needles at the ready. I served detention for wearing nail polish, which I actually had removed, though not to a godly degree of cleanliness. Harlots wear nail polish, the punishing nun told me. I was eight. In religion class there was constant discipline and rote memorization, but there was, curiously, no Jesus. We never learned about him or his stories; we learned the code for being Catholic, the rules, the how-to, and were reminded that despite all this we would fail.

And yet my son, exposed to no such material, seemed to know, if vaguely, about Jesus—maybe not so much his name, but his face and the basic outline of his story. Calling him “Baby Tommy” made my son sound in the know, the way calling Billie Holiday “Lady Day” can make you sound like you know something about jazz. He seemed a benevolent character, someone who might give you a high five for finishing your broccoli.

It turns out Baby Tommy, my son divulged after several persuasive servings of dessert at Christmas lunch, is the narrator of The Legend of Frosty the Snowman, the film he watched in school the day before winter break. He had put together a few truths and a few lies, like hairy tongue or the Hepburn family tree. Our daughter had watched the film as well and happily undermined her brother by pointing out that the narrator is an old man.

“Yeah,” my son confirmed. “Old Tommy. Christmas is about his birthday, when he was a baby.”

My daughter contemplated the Jesus statue. “He does look a lot like the guy in the movie.”

“Was he wearing a robe? With long hair? In bare feet?” I asked, panicking. It was possible a flyer had been sent home, a permission form even, and that I had scrawled my initials on it under the assumption that I could drink my morning coffee in peace if I looked busy. Sign here if you want your child to know Jesus.

Both kids confirmed that Tommy and Jesus sported the same mustache, but now that they thought about it, Tommy didn’t have a beard. I tried to calm myself and appear mildly curious—Oh really, no beard you say?—but I needed reassurance. It was time for visual evidence. My partner and I found the movie on Netflix.

The narrator, we learned, is indeed called Tommy, and he could, minus the half-moon glasses, cropped haircut, and cardigan, pass for a conservative, avuncular Jesus. He is voiced by Burt Reynolds. How much better might my childhood have been had I thought of Burt Reynolds every time I prayed?

In the movie Old Tommy recounts his childhood. His father, the town mayor, was so obsessed with rules that he made childhood miserably devoid of fun. When Frosty appears with his winter magic, plucking children away from chores and piano lessons, Tommy discovers the reason for his father’s strictness: he is a disillusioned magician who gave up on his career and insisted to his son that magic was a bunch of baloney. The future mayor was once a believer—he even had a hat, the same hat Frosty wore, which he thought had special powers. He had, however, repressed his convictions and busied himself with facts and efficiency, things that could be proven and seen.

There are parallels between The Legend of Frosty the Snowman and the Christian story. Both are stories of a father and his relationship with his past, his son, and belief. The film even offers a Judas/Pontius Pilate hybrid. At one point, when Frosty’s charm undermines bedtime schedules and math tests, the school principal—the mayor’s closest friend—organizes a town trial, during which the people accuse the mayor of failing his office. The town votes in a new mayor: the school principal himself, of course, who declares that he will squash all cases of imaginitus, the particular sickness that plagues the children and makes them break established rules. Tommy, however, vows to validate his father’s story and restore his respected name by showing everyone that Frosty is real.

On the surface, Frosty is about magical snowmen and harping adults. All the town’s children seek is joy—and a little bit of faith from their parents that their choices are thoughtful ones. Underneath, though, I detected a cautionary tale about how a parent navigates the blurry territory between protection and restriction. The Legend of Frosty the Snowman isn’t cloaked religious propaganda; it’s a rebel yell of empowerment for kids.

After Christmas lunch, we walked into our town, which looks a lot like the model town of Frosty: a central green dotted with old oaks and walnuts, side streets lined with shops, a library, and three churches. It was an unusually warm day for late December; we wore no jackets. We were sated, and the adults were a little tipsy. The kids skipped ahead, then stopped in front of the church. Of the three churches around the town green, they chose the Catholic one, St. George’s. My son looked at the front door and asked if it was where Baby Tommy lived. I said yes, qualified with a stumbling specification that Baby Tommy wasn’t alive, was a character, a mini rant about the Bible as a historical document—but my son was already through the door.

A lump hardened in my throat. My son, crossing the church threshold, filled me with dread. Though mass was well over and the church was empty as he ran to the altar, where a bronze nativity stood surrounded by red and white poinsettias, I expected the worst. My atheistic parenting would be exposed, and on Christmas Day, of all days. A murder of nuns in black cloaks would swoop from the pews to banish me to the inferno for letting this child refer to Jesus as Baby Tommy, for letting this unbaptized child think he could approach the communion table and behold the shiny chalice and the pyx. They’d assign him to some ring of purgatory where he would write Jesus’ name again and again for eternity, with a dull pencil on wet paper.

“Mommy, look, it’s Baby Tommy!” he shouted with joy, foot on the first step of the altar. I couldn’t speak. A man in cream-colored vestments approached. I held my breath. “Go on, son. You can go wherever you’d like,” he said, and smiled at me. I thought the priest must be lying: of course my child couldn’t go where he wanted in church! Only priests could do that. My son crouched next to the manger and remarked on the baby’s cuteness.

Nothing happened, except that my son fell in love with the place.

When the sunlight shone through the stained-glass windows, he gasped. “It’s so design!” he exclaimed, striding down the aisles between the pews. It was difficult getting him out the door.

The praise piled up: the church was “the prettiest, most awesome place,” first in the whole town and then on the whole earth. “Mommy,” he asked, “can we go back and visit Baby Tommy again?”

If I were to resist his enthusiasm, try to redirect it or qualify it, I would be doing so out of fear, but, I like to think, well-founded fear based on experience. I didn’t want any restrictions placed on his evolving, beautiful self who, in his own words, was “just a boy who liked fancy.” If eight-year-old girls with nail polish were harlots, what would the nuns call a five-year-old boy carrying a sequined purse?

But I was restricting him. I was extrapolating my own experience of religion and schooling onto his world, where Jesus sounded like Burt Reynolds and lived as a bronze baby in a beautiful house, this mythical story he had invented, giving in to his imaginitus. My own family myths passed time and filled empty hours, but my son’s myth had evolved to a higher purpose: it gave him joy.

We didn’t go back to church, not for months. My son mentioned Baby Tommy a few times, and when we drove past the building he never failed to remark on its loveliness. He spent more time asking other questions, the sort that people so often want religion to answer: Why do people die? Where do they go when they die? If I dream of dying, will I wake up dead? If I choose not to die, could I live forever?

His questions had begun before the Christmas of Baby Tommy, following the death of the father of his best friend, the husband of my best friend, by suicide the previous May. We’d had to explain to our kids why the jovial man they saw at least once a week no longer existed. It’s not easy when the death involves suicide. The impulse is to cover up, to fabricate. Though her husband shot himself, my friend planned to explain his death to her daughter, and by extension to our kids, as an accident—a fall, a heart attack, a stroke. She consulted a child psychologist, who insisted the child must understand the how with the that, the full epistemology of death, or else the child would feel betrayed when she eventually, inevitably learned the truth.

In the case of mental illness, which plagued the husband, the psychologist recommended the parent explain that the deceased was ill in his thoughts, the same way our stomachs are ill when we have the flu, and for him it made the most sense to stop living. Simply, he chose to die. Mentioning the gun, the exact method, was optional, and my friend chose to omit these details. I was loyal to her choice, explaining the death as she did, quoting the psychologist verbatim. It was the truth, sketched in pale strokes, with room left for shading, filling in the definition with myth.

My daughter accepted the party line and backed off, but my son dwelled on the death. Brushing his teeth, putting on his shoes, he’d launch into an internal dialogue.

Where’s Cora’s dad? Oh yeah, he died.

Do you remember when Uncle Aidan made us pancakes? He’s dead now.

If I choose to die, will I see Uncle Aidan? I wonder what he’ll look like.

People turn to religion for meaning, particularly in extreme experiences of sadness and loss; why should a child not as well, and expect the same reassurance? In his oblique exposure to Christmas and Christian narratives, my son recognized a kindred spirit of questioning, some promise of knowledge. What a surprise that a building with colorful windows and murmured stories about a man dying and coming back to life intrigued him. Church for him was a place of solace and comfort. The double standards were manifold: we deleted the violent details of a death in our circle of friends, and we brought him to a place where they suspended from the ceiling the bloody body of a man nailed to a cross. But for my son, the church wasn’t restrictive; it was a place of openness and freedom.

As Easter approached, parishioners tied purple ribbons around the trees in front of St. George’s. My son noticed the new decorations and asked if we could visit Baby Tommy. As a penance of sorts, I suggested we go on Easter Sunday.

Inside the church there was a festive feeling in the air, that undeniable buzz of a happy mob. When the priest began his Easter sermon, my son turned to me with a whispered question: “Where is Jesus now?”

I don’t know what happened to Baby Tommy. In the instant the ritual of the mass began, my son became serious. He spent the service besotted, awestruck that the people around him knew what words to say and when, that there was music and incense and a man with a microphone talking about a dead person walking out of a tomb. My daughter looked annoyed that she was left out, that these people knew what to say. I caught her mouthing the words to “Here Is the Church” and flipping her hands over to wiggle her fingers for the people; she scanned the room, nodding her head in approval of the likeness. My partner stood smiling at our kids.

My thoughts went to my gay friends who had to hide their sexuality from the church, the centuries of inquisition and missionary work that led to so much misery, the withholding of literacy that for much of Christian history equated knowledge of scripture with death on a pile of burning sticks. I turned my attention to a woman in the corner of the room, kneeling in supplication on the stone floor, and tried to see the whole church filled with loving intention. I watched a little girl hug my daughter during the sign of peace and people hold hands during one particular prayer. I listened to the cantor lead the choir with his operatic vibrato. I thought of the distraught Mary Magdalene with her pots of myrrh and sweet cinnamon, staring into the empty sepulcher, wondering where Jesus had gone. I thought of Burt Reynolds tapping her on the shoulder, the relief on her face when she had an answer.

“How do they know so much about Jesus?” my son asked me, weeks later as we walked by the church. My stomach clenched. I wanted to change the subject. I still want to change the subject. Instead, I told him they believed in some stories they were told, and this made them happy. And that if he wanted to learn more, I would help him.