Voting is important. It isn’t sacred.

Casting your ballot means voicing a preference—not a moral conviction or deep, spiritual alignment.

(Photo: Lorie Shaull / Creative Commons)

It’s time to vote again, to carry out a basic task of democracy. Or, as some would have it, to fulfill our sacred duty as Americans. This sort of elevated language for voting is common in our society. And indeed, the ability to vote—the right under the law, the access and time to get to the polls, protection from suppression and intimidation once you do—is a hard-won cornerstone of democracy. As for an individual’s choice to exercise this right, that’s important, too—but is it helpful to talk about it in such high, quasi-religious terms? There are at least two reasons to think that it isn’t.

First, voting as a sacred duty suggests the need for a deeply personal, even spiritual alignment with a candidate. Americans often bemoan their electoral choice between “the lesser of two evils” as a soul-crushing compromise, a challenge to their integrity. But why must one’s vote be so deeply felt? In the US system, a general election presents voters with a straightforward task: choose pragmatically between two main candidates. Call your choice “good” or call it “less evil”; it doesn’t really matter. You’re voicing a preference, not a moral conviction.

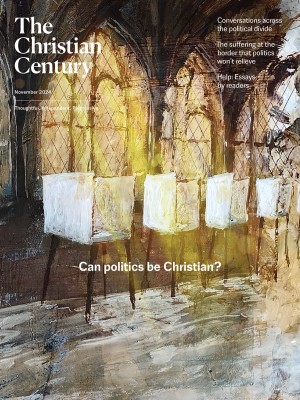

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

The other problem is that elevated language positions voting as the pinnacle of a person’s civic life. In reality it’s just a first step—necessary but not remotely sufficient. Voting merely scratches the surface of political participation.

The deeper work of politics is ongoing and more difficult. Organizing, mobilization, issue advocacy—such undertakings require far more commitment and wherewithal than voting does. And while they too involve pragmatism, there’s also space in the work for genuine idealism, for demanding more from our political leaders.

A lot of Americans are unhappy with their options in this election. Anti-MAGA conservatives feel like they don’t have a party anymore. Progressives are frustrated with Democratic policies on fossil fuel extraction, the southern border, the war in Gaza, and more. Many people are finding it hard to give either presidential candidate their wholehearted support.

Churches, of course, aren’t allowed to. Neither is this magazine. While this rule comes courtesy of the IRS, there is also theological wisdom in keeping partisanship at arm’s length. And we shouldn’t expect any political program to usher in the kingdom of God. But voting in a general election doesn’t require our endorsement or loyalty. It just requires making an informed, pragmatic choice between two options. Then we get on to the deeper, more difficult work of politics.

To engage in that work, we don’t need a president who reflects our deepest moral vision. We do, however, need a president committed to democracy, equal rights, and the rule of law. Such baseline commitments in the halls of power are a necessary condition for effective organizing and advocacy outside those halls. They are the water in which political action swims. Our democratic system relies on a president who seeks to strengthen that system rather than undermine it, to make it work for the many rather than enrich the few. The fact that some will read this paragraph as partisan shows just how much our democratic health has decayed.

Party and policy views aside, we need a president who seeks to preserve what’s left of that health, and it isn’t partisan or one-sided to say so. We need to vote now, pragmatically and without angst, so that we can keep doing the deeper work of politics tomorrow.