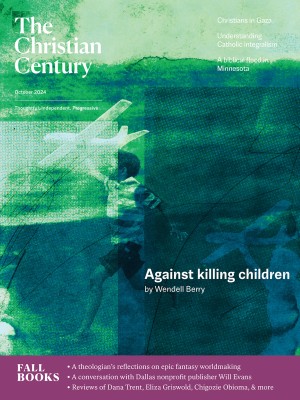

Against killing children

We have become a society of people who cannot prevent our own children from being killed in their classrooms—and who do not much mind the killing of other people’s children by weapons of war.

Century illustration (Source image: Getty)

Soon enough, and somewhat to my surprise, I have become an aged man. For many years I have been an advocate for the good and goods in which I have invested my heart. I am a patriot but not a nationalist. Since the Vietnam years, I have opposed our wars of national adventure, and I have opposed the extractive industrialism that passes with us for a national economy. I have opposed the dominant attitudes and technologies by which we are destroying, and have too nearly destroyed, the economic landscapes of our country, our country itself, our land. The different manifestations of our destructiveness are all parts of one thing: a global corporate economy concentrated upon the effort to turn to profit everything that can be subdued to its methods. Whatever cannot be made directly profitable—the lives and needs of children, let us say—it ignores and thus draws into the vortex of its destruction.

And so, as a “late” essay, I want to address a problem, in fact a disaster, that I have not heretofore said enough about: our destruction of children. We of the United States of America have now grown accustomed to the killing of children. We still regard it as sensational, with a remnant revulsion; it is often a “news item.” But sensation wears out fast. The roving eyes of the media hesitate a due moment over the current sensation and hurry on to the next. Perhaps experts may devote an article or column to the matter, but they also must hurry on, for disasters continue to happen, child killing is only one of them, and all must be given their moment in the schedule of sensations.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

We all agree that we are living in an exceedingly troubled time, and it finally occurs to me that we ought to think of child killing not as a part or a symptom but instead as the center, the nucleus, the very eye of our trouble: the plainest measure of our betrayal of what we used to call our humanity. I know that I am drawn to this labor by my tenderness and fear for my four great-granddaughters. But I am drawn to it also because I was once a child, and like many children of my generation, I enjoyed a freedom that has become rare, almost extinct. The best part of my early education was the free, unsupervised playing and rambling with other children in our small towns and the freedom to wander in fields and woods. We were to a degree endangered, of course, by the world’s native hazards and our inexperience, but we acquired experience, too, the kind of experience that supervision excludes, and thus something in the way of caution.

Today in our not very free country, children are first in line to be unfree. They are enclosed in specialized child worlds constructed for them by frightened and mostly absent adults. And yet they are in danger, now not so much from nature and accident as from an industrial instrument made expressly for death-dealing, wielded against them by an irate or maddened gunslinger. They are not safe in their schools, and if not there then obviously not in any public place.

A new and most acute pain comes into the heart with the thought of little children learning in school their poor means of protecting themselves against a gunman come to kill them. It is convenient, a relief of sorts, to look upon this as anomalous, supposing that this killing of children in school is perpetrated by people exceptionally crazed or maddened, or to blame it on the proliferation of guns or the inadequacy of gun laws. There may be some truth in these explanations. It seems that people are becoming more likely to be crazed by a popular anger or hatred or some extremity of politics. It is true that people in general own too many guns.

It is certainly true, moreover, that our political representatives are now measuring up to remarkably low standards. The dumbfoundment of many of them by awe and fear of the Second Amendment is abject and cowardly. As is clear in its language, the Second Amendment does not confer a right that is absolute or unlimited. Like any other right, like any freedom, the right to bear arms must have its encounter with responsibility and make its submission. Billionaires should not be allowed to own a personal air force or nuclear bomb. No more should any other private citizen have a right to sell or buy or use in any way an assault rifle, a weapon whose only purpose is to kill a lot of people in a hurry.

But I am attempting to talk here about a radical reduction of childhood, which can happen only by way of a radical reduction of parenthood, of adulthood, of what it means to be a grown-up human being. It is not enough to single out offenders or groups of offenders, as I have been doing, and lay blame. These reductions are national in scope. In one way or another they involve us all, and among their implications is the killing of children. I dread to say so, but we have become a child-killing nation. The kindest way to put this is to say that we have become a society of people who cannot prevent our own children from being killed in their classrooms or in other gathering places and who do not much mind the killing of other people’s children by weapons of war that we have made and assigned to that purpose. Sooner or later, we will have to ask how we can so disvalue the lives of other people’s children without, by the same willingness, disvaluing the lives of our own.

Child killing is the plainest measure of our betrayal of what we used to call our humanity.

The history of war making against civilian populations, from our Civil War to our bombing of Hiroshima, is well known. It follows one of the routes of technological progress. Perhaps, because the scale so far has been smaller, it is easier to overlook or forget the continuation of this progress in the succession of foreign wars of so-called national defense, from Korea to Afghanistan to our (so far) indirect participation in Ukraine and in Israel and Gaza. It has continued also in our now-and-then-remembered stockpiling of nuclear weapons. I saw in the New York Times of June 6, 2023, that Hanford, in Washington State, “was part of a network of plants that made more than 60,000 nuclear bombs.”

The smaller of our wars, using conventional weapons and “smart weapons” aimed only, supposedly, at combatants, may permit us to think that children are killed only accidently, that their sufferings and deaths are only collateral damage, for which the perpetrator may be in some fashion innocent. But bombings meant to destroy whole cities offer no such convenience. Those can only be the result of official policy—policy that presumes public consent—intending to kill a whole population, including of course all the innocent small children, as well as all the innocent birds, animals, and plants, as well as the entire built structure of human life. The intention, in short, is total destruction. (And now, the chickens as ever are coming home to roost. Israel invokes the US history of child-killing war to justify its own child-killing war, as perhaps Hamas does also.) Our nuclear stockpile can exist only by the same intention, with the same consent, which has belonged to us now for more than three-quarters of a century. The value of the lives of the children killed by such a mode of warfare has thus been reduced, by us, to nothing.

We have assumed, evidently, that we can commit or tolerate so great a depreciation of life at no cost to ourselves. But how do we preserve the wholeness of our hearts against the force and effect of that nothing? How do we keep it from reducing our valuation of our own children?

And to so much difficulty we have added a dimension of absurdity that baffles and degrades us even further: 60,000 nuclear bombs? Who can look upon such an extravagance as good? Only those, I guess, who gain from the production and maintenance of so much “national defense” a wage of power and money to enjoy for a good while, as they must hope, before the stroke of the doom they have prepared. The absurdity of this is revealed by questions that are merely obvious. How many times does a nation need to destroy civilization or the human race or the world as we have known it in order to win a war? What does any nation possess that is worth defending by so much destruction? Or that can be so defended, or that can survive such a defense? What that is good can survive the employment of so much evil in its defense?

I fear that in saying these terrible things, I am giving the impression that this problem is offensive only according to some measure devised by me, not by any external standard. In fact I have so far been attempting, by habit, to speak as a Christian. I would like now to make this explicit—and to do so by taking as seriously as I can the conventional claim that this is a Christian nation and therefore submitted and accountable to the laws of God as set forth in the Bible.

I am aware of course of the numerous people in this nation who are not Christians, or who dispute the claim that the nation is Christian, or who are hostile to religious belief of any kind. I am aware, above all, of the sometimes scandalous differences between the teaching and example of Christ and the behavior of Christians in most of the Years of Our Lord. But I am aware also of the prominence of Christianity, in its several versions, in our history and our cultural and artistic inheritance. For a standard by which to measure the consistency and quality of our shared or public life at this time, I don’t know where else to look. Though I am not a cleric or a scholar but only an amateur reader of books, I mean to use the Bible’s laws, and what I take to be its sense, as a practical standard to examine the ways we think and act in the 21st century.

About here, it seems to me, I come under the necessity to answer those who think that, from the perspective of the science and civilization of the 21st century, the teachings of the Bible are outdated and irrelevant—which is to say, pretty much, that old truth cannot be true and that one now reads old books to learn about them but not from them. This supposes that there is such a thing as a purely modern human mind, free of history and superstition, free of all antiquated views of nature and human nature, entirely materialist and mechanical, factual and true if not now then soon. This is a mind entirely resident in the human brain, famously big, that can make up out of thin air any rules needed for the guidance of human behavior.

There have always been, on the contrary, people learned and intelligent who have engaged the Bible and Christian tradition seriously and with an awareness of the trial and the testing it must be for themselves and for humankind.

Of these I will offer as an example the distinguished diplomat and historian George F. Kennan. In 1982, Kennan published The Nuclear Delusion, which includes his essay “A Christian’s View of the Arms Race.” This man’s thinking about the great problems of modern warfare, so far as I am acquainted with it, is intelligent, informed, and thorough. He saw clearly the urgency of the crisis of nuclear weapons. But he saw too that the “conventional” technology of modern war was, like the nuclear bomb, incapable of distinguishing between combatants and noncombatants, and therefore that “war itself . . . will have to be in some way ruled out.”

In his essay he presents himself with appropriate modesty: “I hold myself to be a Christian, in the imperfect way that so many others do.” He speaks of the ethical confusion in which history has placed us with respect to the possible use of a nuclear bomb:

One of the rules of warfare was the prescription that weapons should be employed in a manner calculated to bring an absolute minimum of hardship to noncombatants and to the entire infrastructure of civilian life. This principle was of course offended against in the most serious way in World War II; and our nuclear strategists seem to assume that, this being the case, it has now been sanctioned and legitimized by precedent.

But, he says, even if that rule of war were not “prescribed by law and treaty, it should . . . be prescribed by Christian conscience.” And then he goes to what—for him as for me and I assume still for many people—is the very quick of the issue: “Victory, as the consequences of recent wars have taught us, is ephemeral, but the killing of even one innocent child is an irremediable fact, the reality of which can never be eradicated.”

This sentence is crucial both to Kennan’s essay and to this essay of mine. Kennan could have told us, as we have been told many times, that a nuclear bombing of a large city would kill thousands of children, and we would read right on—because the human imagination does not respond to large numbers, to statistics. When he instead asks us to consider the killing of one innocent child, we stop, and we imagine what would be the absolute finality of the death of a child we love; we imagine unending sorrow. By this immensity of the intentional killing of one child, Kennan makes the technology of mass destruction subject to Christian conscience. And Christian conscience, which subjects the events of time to the judgment of eternity, seems to speak for itself in Kennan’s conclusion:

The readiness to use nuclear weapons against other human beings—against people whom we do not know, whom we have never seen, and whose guilt or innocence it is not for us to establish—and, in doing so, to place in jeopardy the natural structure upon which all civilization rests, as though the safety and the perceived interests of our own generation were more important than everything that has ever taken place or could take place in civilization: this is nothing less than a presumption, a blasphemy, an indignity—an indignity of monstrous dimensions—offered to God!

I believe that this is fairly exactly what Christian conscience would say in response to this jeopardy of our souls that has only grown worse in the 42 years since Kennan wrote his essay.

In a Christian nation one might reasonably expect Christian conscience to have a lively part in the national conversation, so that no policy of war making could be made without hearing the voice of that conscience and so coming under pressure to respond. But Kennan’s statement, lonely enough when it was written, still seeks for hearers, and it enforces several questions: Who now in our prominent institutions would have the courage to repeat it? Who in the high places of our government would have ears to hear it? Who in public life could quote without fear or embarrassment any saying of Jesus on the subject of peace? Martin Luther King Jr. could do so, and did so. But who now?

I don’t know. Somebody, I hope. What I do know is that our official policy now rests, apparently with no second thought, upon the doctrine of preparedness—preparedness, that is to say, for the worst, only for the worst—which requires the means and the will to annihilate an enemy at the cost only of being annihilated ourselves. Our thousands of nuclear warheads prepare us for a victory that is perfectly and hopelessly absurd. Not only do we risk unspeakable horror by the intentional use of these weapons, but we run the same risk in possessing them, because of the possibility that they may be exploded by error or accident.

And so we have got to ask if there is a point at which Christian conscience, or any conscience, can say no to a technological “advance” of any kind. I will mention again, as I have done often before, the Old Order Amish, who have maintained an effective freedom of choice for themselves by limiting the economic scale of their lives and by asking of any proposed innovation a single question: “What will this do to our community?” Otherwise, the conscience of our country, Christian though it may be, is at one with or more or less surrendered to the doctrine of technological progress, which apparently reduces to the assumption that what can be done must be done.

Moral choice and even moral refusal are possible in relation to nuclear weapons. We know this not from the example of a community but from that of highly principled individuals. Physicist I. I. Rabi refused J. Robert Oppenheimer’s invitation to join the Manhattan Project because he could not bear the idea of a nuclear weapon as “the culmination of three centuries of physics.” According to the New York Times (October 3, 2023), another physicist, Lise Meitner, refused the same invitation: “I will have nothing to do with a bomb.”

In a 1998 letter to historian John Lukacs, Kennan offers a reasoned dissent from the dominion of technological progress:

There will now come what I would expect to be a long period of virtual enslavement. . . . The automobile, television . . . drugs, and now the computer culture, have become not the enlargers of life they were originally seen to be, but the restrictors of it—forms of entrapment, all of them, from which people no longer know how to extract themselves.

It may surprise us to recognize that none of those commodities came about by popular demand or to answer a perceived need. Most people did not desire or think of them until they were available. The supply brought forth the demand. This inversion of the natural order seems to be the rule of the industrial economy. Trainability, as we know from our dealings with parrots and dogs, is a mark of intelligence. Perhaps because of our big brains, we were easily trained to want television sets and computers. As for Kennan’s prophecy of virtual enslavement, we now hear, only 26 years later, the voices of experts advising us of our need to know how to brand ourselves—the better, obviously, to sell ourselves. Although in this arrangement the money is paid to ourselves, we have nonetheless been sold and bought, as slaves always have been sold and bought.

How comes it that we who inherited a tradition of freedom—who once knew that within obvious limits we were free to choose between good and evil, truth and falsehood, yes and no—now submit our conscience, of whatever design, to the inevitability of whatever has happened and whatever will happen? How do we answer the scientists who, on the one hand, advise us that freedom of choice is a superstition or a self-coddling delusion and, on the other hand, beg us to choose the remedy that they prescribe for whichever calamity they have presently in view? What do we say to the university intellectuals who, to avoid the subjectivity of a moral stand, speak of the inevitability of what is morally indefensible?

To answer, let us remove these questions from the thin air that now surrounds our public talk about freedom and place them in the force field of the Bible, and let us begin at the beginning. Genesis 1:27 declares that “God created man in his own image, in the image of God created he him: male and female created he them.” I would like to read that for what it is: not history or science, as we understand those terms, but a part of the King James translation of a Hebrew poem about the origin of everything. As religious statements often do, this one places us between two perfectly symmetrical impossibilities: nobody can prove that God created us in his own image, and nobody can prove that he did not.

This verse follows immediately the verse granting us dominion over the other creatures—the verse, read alone, that is so scandalous among environmentalists looking for somebody to blame. But “dominion” does not imply permission or a right to destroy things. As I am going to try to show, it is the peril of dominion that calls forth the biblical laws. As I read them, the two verses are closely related, and the second imposes a stark qualification upon the first. God made us in his image—as his likenesses, not his equals. That our dominion, which it seems we have fearfully and without limit, is subject to the condition of the next verse becomes, even before the Fall, an extreme difficulty. To be like God but not God is to be free to choose and to choose wrong. After the Fall, our likeness to God makes us free to work and to work badly.

To be made in the image of God is to be made unique among the other creatures, to be made especially uncomfortable in our dealings with them and therefore especially in need of instruction. Unlike the other creatures, we need laws to keep us in harmony with heaven and earth and with one another. And so God reveals himself from the first as a lawgiver. His laws come as light in darkness, allowing us even when we disobey them—which we are free of course to do and often have done—to see what we are doing and to know what is expected of us. This is why the blessed man of the first Psalm delights “in the law of the Lord.” He recognizes the relief and the immense privilege of knowing the difference between right and wrong.

It is remarkable that after the Fall expectations are not adjusted downward to suit our condition. God doesn’t say, like an indulgent parent or a bad teacher, “You’re doing pretty well for fallen people.” He says with terrible simplicity: “Be perfect.” That confers a dignity upon us that is hard to bear. For many of us it is not bearable, and so we don’t try to bear it. But I have read of people, heard of people, even known one or two, who have stood up to the burden and borne it well. And it seems to me that such people offer to the rest of us an authentic solace and source of hope. If not them, then who?

Sooner or later, we will have to ask how we can so disvalue the lives of other people’s children without disvaluing the lives of our own.

From the beginning, Jews and Christians are given a definition of ourselves—made in the image of God—which imposes upon us a burden, requiring much but not too much if the best of us have becomingly borne it, and by its requiring it teaches us much about the world and about ourselves. The problem with this, in addition to its hardship in an age devoted to comfort, is the mystery of it. It belongs to the mystery of existence, ours and that of everything else. Why are we here, in a world somewhat uglified by us but still to many of us mainly beautiful? That it was once said on highest authority to be good is, even now, not an opinion altogether lonely. But such perceptions do not lead to questions that lead to answers. They simply stall us in the presence of mystery.

In a materialist age, mysteries are embarrassing, even threatening, and they have to be ignored or worked around. And materialism, it seems, is subtly infectious. Though we may not have tried to be, though we may not have realized that we were learning to be, we all are materialists now, entrapped in our determined need to find a material cause for every perceived effect. For materialists, life becomes a sort of detective story: What is the cause of this effect? And then: What is the cause of the cause, and the cause of the cause of the cause?—until we come to the Big Bang, of which everything is an effect but which so far has not been found to have caused itself.

“Made in the image of God” clearly is not acceptable to this way of thought. And so by way of progress and to accommodate our fear of mystery, scientists at first replaced our old definition with one they thought we could understand: we are only human, which is to say a kind of animal. To account for our difference from the other animals, the scientists specified that we have big brains. But once a reduction of this sort has begun, it apparently cannot be kept from going as far as science or some scientists can take it. In their 2010 book The Grand Design, Stephen Hawking and Leonard Mlodinow take it as far, I assume, as was possible at that time: “It seems that we are no more than biological machines and that free will is just an illusion.”

I mean no harm to scientists, some of whom I admire and depend on. But it happens that this comedown from the image of God to biological machines is the work entirely of scientists. This final (so far) reduction by Hawking and Mlodinow requires our thanks for the honesty of their way of wording it. “It seems,” they are obliged to say because of their inability to prove what they are going to say. And if we are, as they say, “biological machines,” then it follows, as it must, “that free will is just an illusion.” They have brought themselves to a perfect determinism. We are left to conclude that the two of them wrote their book because, as biological machines, they could not do otherwise. Thus they have replaced an immense and mysterious complexity with a simplicity as tidy and small as it (so far) can be made. And who among us materialists can avoid some sense of their relief? For with one logical heave they have shrugged off the whole burden and agony of moral choice and moral failure, freedom and responsibility, along with the tangle and trouble of human history so far.

In the descent of our understanding of ourselves from “made in the image of God” to only humans to animals to machines, I don’t know exactly when or how free will begins to be replaced by determinism. It is clear to me only that materialism itself is deterministic to the extent that it disables the high principles and ideals that we once looked to as motives—love, reverence, beauty, mercy, faith, sympathy, compassion, kindness, and the rest—which are not materials and do not necessarily lead to material results. Under the rule of materialism, we are motivated by what we perceive as the goodness or the good consequences of material commodities—ease, comfort, speed, facts, wealth, power, and so on—with which we are now obsessed.

Meanwhile, we Americans along with the people of several other nations are “protected” by our stockpiles of nuclear weapons—from which we are protected in truth only by the world’s rulers’ fear, so far, of using them. So far as I know, the accumulation and dispersal of these weapons cannot be openly opposed by a political or governmental insider. Only an outsider, such as Kennan came to be, can speak in opposition. Kennan devoted a good part of his life to demonstrating over and over again the sheer absurdity of these weapons. He was eminently prepared by intelligence, learning, and experience for this argument. He died in 2005. Who are his successors?

I am sure that he has successors. I believe that there always will be people sane enough and compassionate enough to trouble themselves in behalf of peace. I am not a politician or a journalist, and so my sense of the state of things is somewhat impressionistic. My impression is that Kennan has no successor as distinguished and capable as he was. My further impression is that there is in the United States no peace establishment. We have a war (or “defense”) establishment, involving a huge annual outlay of money, a huge arsenal of military technology, a huge staff of officials and bureaucrats, and a huge payroll. But we have no secretary of peace, no department of peace, no academy or curriculum of peace. If a war breaks out, provided it is not one of our own, our leaders offer as a way of restoring peace mainly a supply of the most advanced weapons to their preferred side. It’s not clear that anyone tries to compute the worth of destroyed lives or of destroyed dwellings or of damages to the human infrastructure and the natural world. Nobody weighs these damages against the worth of the proposed victory.

If one is not convinced of the inevitability of war or of war as a necessary and acceptable solution or of victory as a final good, then one may notice that the only real winners of these industrial wars are the war industries. One may notice that in the background of these wars of national defense are people for whom a war is a part of business, the payoff of an economy in many ways violent even should there be no war. And then one may begin to suspect that peace may be so little a matter of political interest because there is no money in it. War clearly is good for such an economy as ours, but who is investing in peace? Peace is in many ways a bargain for mere people and other creatures and the earth they inhabit. But peace is cheap. It requires the disuse of technologies of violence, of which the misuse is preferred by the people who count.

Should we not ask if war imposes any cost upon the war industries, or upon any industry to which war is profitable? In time of war mere people are expected to put their lives at risk. This is taken for granted; it is normal. But in recent years I have been asking people who ought to know, including an army general with whom I spoke at some length, if during a war it were not normal, as a part of patriotism, for the great corporations of national defense to reduce their charges for weapons and other products sold to the government. Not one of my witnesses so far has ever heard of such a sacrifice. No, war is the business of businesses immune to the penalties paid to war by citizenship. To further baffle us there is the international arms trade, which conducts itself according to the rules merely of business in the interest merely of business.

As a matter of course, we the people of the United States observe our world of active and potential violence, paying day by day our share of the cost of it, consuming the news of it, suffering the outbreak of it at times in the classrooms of our children. And where is the prominent peace movement that would normally be expected of a Christian country, or even of a sane country? How can we remember “But I say unto you, Love your enemies” and not see that we are involved in a world-destroying, life-destroying betrayal? How can we hear “Suffer little children, and forbid them not, to come unto me: for of such is the kingdom of heaven” and, looking at our own little children, merely regret that they may be killed by an assault rifle in the hands of a fellow citizen, or be merely sorry that thousands of little children like our own have been and are being killed by weapons made and paid for by us? Can we not speak at least an audible no to the meaningless suffering and death of these most precious and helpless ones given in trust into our care?