The meaning of a sermon

I’m sure these faithful people have heard all of these words before. So what is my task here?

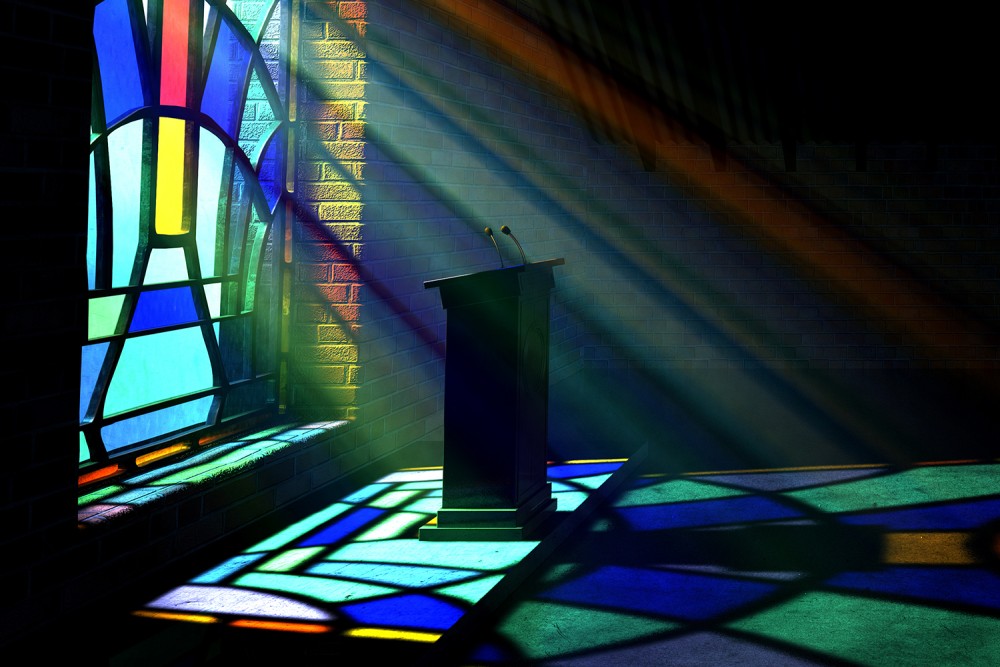

(Photo: allanswart / iStock / Getty)

On the Monday after preaching, as I think about what all of those words are doing now that they’re out in the world, my mind wanders to a scene from Marilynne Robinson’s novel Lila. The title character carries on an imaginary conversation with John Ames, the small-town pastor who will later become her husband. She wonders about the purpose of his work, about why he steps into the pulpit week after week and tries to come up with something more to say, as if he hadn’t already said the week before what had to be said about the same book and the same God. “What do you ever tell people in a sermon except that things that happen mean something?” she asks. “Some man dies somewhere a long time ago and that means something. People eat a bit of bread and that means something.”

Her questions are my own as I prepare another sermon, this week as a guest preacher at a friend’s church. I’m sure these faithful people have heard all of these words before. I’m confident that they know the gospel—that preachers, Sunday after Sunday, have shared with them the meaning of God for their lives. That Jesus, crucified under Pontius Pilate, was resurrected—and that those events mean something. That, at the Lord’s Table, the bread we break and the cup we drink mean something. Those happenings involve us in a significance that we discover over time with one another—a communal learning, a growing into the meaningfulness of the gospel. The task of the preacher is to point out the connections along the way—to remind us that our lives are bound to God’s life, that our world is first and foremost God’s world, that the promise of the gospel includes nothing less than the liberation of all creation from sin’s power to do violence to God’s goodness in us and around us.

Preachers bear witness to God’s life among us, to the God whose love is our salvation—a saving of our world and ourselves from our worst tendencies, our hell-bent desires. Lila is right. All we do is say, again and again, that there’s meaning here, that there’s a meaningfulness to this life we’ve been given. In Christ, God’s own life is given for this precious existence we share with the rest of creation, a communal life held together in the animating and sustaining power of the Holy Spirit. There is something instead of nothing because God loves to love. To wonder about the meaning of things is to wander—with every relationship, with our attention to both the astonishing and the mundane—into the mysteries of that love.