Clockwise from upper left: Igor Alecsander / SteveLuker / _ultraforma_ / Guven Ozdemir (All via Getty)

The Buechner Narrative Writing Project honors the life and legacy of writer and theologian Frederick Buechner with the aim of nurturing the art of spiritual writing and reflection. Readers are invited to submit first-person narratives (under 1,000 words). Read more.

Religion and unreligion are both sinful to the degree that they widen the gap between you and the people who don’t share your views.

—Frederick Buechner, Wishful Thinking

I know all the stories. I was the kid who always paid close attention to the stories, especially family stories that went all the way back to my great-great-great-grandfather, Joshua, who was bought and sold as North Carolina chattel in the 19th century. I know that as a Black man descended from enslaved people it is a rare privilege to be able to trace my roots that far. I know that such memory is a blessing. I also know that my ancestors fought and labored to keep this memory alive—especially my maternal grandmother.

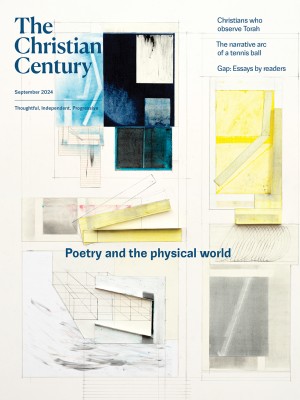

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

A would-be genealogist, my grandmother was determined that I would know all of our stories. She was determined that cancer would not stop the stories even as it stopped her heart. She deposited all the stories with me before she transitioned to her rest. There were stories about great-granddaddy Bill crashing car after car. There were stories of great-great-granddaddy Henry striking forth from enslavement, taking on the surname Goddard upon emancipation because he felt it reflected his love for and freedom in the hand of his Creator. The stories were our gold because my people didn’t have much else precious and costly. We held on fiercely to what little we had: history, relics, and each other.

According to family lore, great-great-great-granddaddy Joshua was born enslaved in the Caribbean but lived to taste freedom in eastern North Carolina. He could not stay with his family of origin in the islands, ripped away by a slaver’s capricious decree, but he made a new one where he was sent. He would have sooner died than lose or leave his chosen family after emancipation. As a result, his son, my great-great-granddaddy Henry, considered family the world’s greatest privilege and responsibility. The same philosophy was passed down to great-grandma Esther, who passed it down to grandma Kay, who handed it down to my mama. Both Ma and Grandma did their best to hand it down to me. They were there to help raise me because they stayed put. Once married, each of them set up a base camp for all their children and grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

That’s what we have always done. It’s why the stories are so sweet, because each generation tells the story out of sacred memories, memories of a life lived together. It is our great treasure.

I went to college out of state, and then I went to graduate school. While there, I met my wife, who also came from a family of stay-put people, to borrow the potent words of Kunta Kinte in Alex Haley’s Roots. But as my wife and I met each other, we also met destinies that would fling us far away from our respective family homes in Virginia and South Carolina. Now my children are being raised away from everything I knew. They are part of a generation that feels at home in what still feels like a strange land, and they don’t get back nearly enough to feel the joy I do when we head up I-85.

It is a paralyzing paradox. My children are thriving in so many ways, but they do not know the joy of spending summers with grandma and great-grandma. They know so much, but they do not know fun summer days ripping and running with their cousins from down the street. They are not living as I lived. Be sure, they have grandparents and family that love them truly. But they are separated by a gap, not in close proximity.

We grieve. Sometimes it feels like we are experiencing grief too deep to be solely our own. It seems some days that we are conduits for the grief of generations. Sometimes the guilt is unspeakable. Our little ones don’t eat at the tables of their people. They are not growing up in the cloister of their kin. So, my wife and I grieve. Every birthday. Every July 4th. Every Easter. We grieve, even though our children are blessed and happy, because they do not sit on the knees of the ones who soothed our souls. Some who are still back home and some who have moved to a higher home.

Most days, our presence must be enough. Our knees have to be enough. Our hugs have to do double and triple duty. It is hard. Hardest when our children are sick or have a bad day at school and we feel like we are missing the genius of the generations. When we are guessing at which remedy grandma would have used. When we are wondering what wisdom granddaddy would have shared.

Yet we are finally finding the humility and hope to say, “This will be okay. Our children are loved fiercely right where they are.” Because there is no distance in spirit; in the truest sense, the ones who kissed our boo-boos and loved our pain away are as close to our children as they would be back home. No, my little ones do not eat exactly as we ate, and they do not speak exactly as we spoke. They do not spend long weekends and every holiday with extended family, catching lightning bugs and playing in the churchyard, but they are strong and covered and I couldn’t be prouder of how they are growing right where they are. They have a new world to live through and a new village to love and be loved by. So, we will make new stories and eat at a new table—because the Lord of the feast and the presence of our foreparents are still with us, right where we are.

Ray Speller

Aiken, SC

It was 2005, just a year after my husband had died. I felt I needed to get away, even though I didn’t quite know where. I knew I wanted to be safe, and I felt I didn’t have the energy to try to communicate in a language I didn’t know. I remembered Gladstone’s Library in North Wales, where a professor I knew had researched the healing traditions of the Church of England. She hadn’t told me I should go there, but I knew it was a place I could get to by train from London. So I signed up for a short course being offered there on the Desert Mothers and Fathers.

The train route involved a change at Crewe. And so it was during that first international trip on my own that I first heard the expression, “Mind the gap.” It’s in a recorded message played over the speakers to warn passengers of the distance between platform and train car, some of these gaps subtle and others more pronounced. One of the most notable readers of this gentle but insistent warning was voice artist and radio announcer Phil Sayer, whose obituary would appear in the New York Times in 2016.

The previous westbound train from Crewe had been canceled, so when mine arrived and the doors opened, I gazed at a platform so filled with people that I couldn’t see a place for my feet or heavy bag to land. I felt the press of those needing to disembark behind me. I didn’t panic so much as I was momentarily confused about how I might maneuver. Suddenly I found myself sprawled on the concrete, surrounded by alarmed faces.

I was fortunate the fall did not produce any injuries to my body or my bag, but it was a harsh and all-too-physical reminder of how my life had changed. My husband’s death had come on gradually and then very hard. As difficult as it had been to see a beloved in such decline and try to ensure his care, my life had at least provided stability. The gap between what I knew and cherished—in a marriage that had given me unconditional love and a sense of freedom—and what I needed to learn as a widow felt more like a chasm.

But Gladstone’s Library turned out to be a place of healing and friendship for me, on that first trip and in the many that have followed. There I discovered the poetry of R. S. Thomas, which has become an important part of my life. Thomas speaks of “this great absence that is like a presence, that compels me to address it without hope of a reply.” A gap? A chasm? The way God reaches me, not as I would want but perhaps in the way my soul needs. In any case, something to be minded.

Jane Brady-Close

Ghent, NY

There was always popcorn, pillows, and the debate over the best viewing position. Should one sit in a comfy chair or lie on the living room carpet? Wait, I need a blanket.

Dad set up the tripod, tipped the center pole, hooked on the shiny screen, and yanked it up to full height. He would then turn on the projector and start the first slide for focusing purposes. One of us would turn off the lights. The slideshow would begin, and our family commentary would have to overcome the whirring of the projector fan.

He spent days organizing the flow of the slides from our latest summer trip. There were always at least three carousels and four or five upside-down or backward slides that would lend some adjustment time for a bathroom break or popcorn refill.

Dad lived for these evenings. He captured moments of our family that became seared into our shared memories. The beauty or wonder of earth, sky, and water. The sourness, happiness, and sleepiness of our expressions; the abstraction of detail and scale; the art of color, shadow, and form. The simplicity of the subject. (It didn’t hurt that he was an award-winning photographer.)

Two years ago, I experienced a private slideshow. It occurred at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital in my recovery room after the removal of a glioblastoma, a level 4 cancerous tumor, from the right side of my brain. My show had no projector, carousels, tripod, or whirring fan—no noise at all. No family surrounded me, no popcorn or jostling for the most comfortable viewing. I might have had a pillow.

Before I awoke from the complicated procedure, quite a few hours passed, as did many images in my mind. What I remember from that time was visually overwhelming and terrifying, yet upon reflection, it was also surprisingly soothing and stimulating.

The images came fast and furious. There was no curator like my father. Centered in my closed-eye mind as I lay on the hospital bed, each image would flicker just long enough for me to see. Sometimes, I would not even see a picture but just know it had been there. I had no throttle, braking mechanism, or method for creating a gap between images; my brain was on auto-play.

The subject matter was familiar images—design projects, legal documents, recent vacations, neighborhood events, and graduations. Past family photos, including slides from my dad’s shows, came up as well. The images were nonsequential, mixed up, some in color and others black and white. They flew through my brain and past my vision as fast as I could perceive. It was exhausting, and I drifted in and out of sleep for hours.

At some point the images became unfamiliar. Harsh, often violent, many erotic, all unknown. Unsettling displacement. Who was that? What was that? These things are not real. Or are they on the way—is this a forecast? An alternative world?

Eventually I opened my eyes and recognized a room, machines, noises in the background, and the voice of a nurse. I closed my eyes and found that the show was over. I somehow wanted it to continue, worried I might have missed something. I began to wonder what the hell it had all been about.

I now believe that during the operation, when the surgeon lifted part of my brain, it may have severed my bank of lifetime images from their proper folders in my head full of files. This slideshow was a visualization of my seeing each image, stamping approval, and restoring it to its original place. My oncology team had little insight to offer. Did they concur with my assessment? Sure. Sounds plausible.

Stephen Opie

Arlington, MA

The gap between the two massive parts of Split Rock grows wider each year as my wife, Elizabeth, and I return to the lake in New Hampshire where we have vacationed for over half a century.

One of the first things we do after settling into the cabin is to canoe around the little peninsula and then around the island so that we can pay Splits a visit, between the island and the spot we call the Point on the opposite shore. The ice in winter works inexorably, ever so slowly, so that if you had been a newcomer last summer, the difference in the rock would be imperceptible a year later. But those of us who have loved this place for a long time remember when the fissure was little more than a foot wide. Now, after you swim from the sandy beach at the Point to Split Rock, you can actually swim through Split Rock to the other side.

Our children, now in their mid-40s, learned to swim at the Point. They would sit in the sand and watch us stroke our way to Split Rock and back. For each of them—first Anne and then the twins, Tom and Chuck—there came a day when they, too, could swim all the way out and return in triumph. Now in retirement, living on the lake from spring until sometime in the fall, we watch our children’s children accomplish the same feat, first with flotation devices and finally on their own. Decades collapse into the shimmering present as three generations swim to Splits and rest for a moment before heading back to shore.

A church conference center used to own the Point and substantial adjacent shoreline acreage. Church retreats and weeklong youth camps brought large groups every afternoon for swimming, boating, fishing, and picnicking. Those days, back when the crevice in the rock was much narrower, are in the past. Memories, however, endure. This past summer, while our daughter and her family were with us, a friend of hers who had been a camper in her teen years came for a visit with her husband. She was eager to see the lake again and to show him where she had spent those formative summer days. When we took them on a boat tour, she exclaimed, “Look! There’s Split Rock!”

The old conference center land is now a nature conservancy, so it will never be developed. Still, change happens around the lake all the time. The gap increases every year. Split Rock remains.

Charles Hambrick-Stowe

Deering, NH

One of my favorite Milwaukee views is from the Hoan Bridge northbound into the city. This bridge spans the harbor, so Lake Michigan is on one side and the city is on the other. The skyline never fails to intrigue me. The reflections off the lake and the glass-encased buildings in the sky repeat the wonderful scene over and over. The Milwaukee Art Museum’s flying wings design is always a treat; it looks like a big bird ready to ascend. I scan the cityscape for the waving flag on top of city hall, the spire of the church I attend, and the Gas Light Building, whose lighted flame on top indicates the weather forecast for the following day. If I’m lucky, I will catch sight of a big freighter in the harbor whose foreign name I recognize having seen before, and I’ll wonder what other lakes and oceans it may have traversed.

Recently I noticed something happening on the Hoan. My once unobstructed view was blocked by chain-link fencing being built on both sides of the bridge. From my vantage point in the car, I could no longer enjoy the panoramic view I so love. It was now made fuzzy by metal links. The fence was constructed meticulously so that when it bumped up against freeway directional poles, there were no gaps. The fence was built closely around them, creating a pocket for the pole structure and prohibiting access to the lake below.

It didn’t take me long to remember that every so often I read of someone ending their life by jumping off this bridge. This fencing is meant to minimize that possibility. I understand that, and I find it sad that this is the solution to those tragedies. There are no gaps in the fence, but there certainly are gaps in our communities, in the ways we don’t seem to be able to care for people. Gaps in our mental health care, our hospitals, our housing opportunities, our hunger relief efforts. All gaps we have yet to successfully address over the long term.

Once I realized the reason for the fence, I was a bit ashamed that my first thought was about how it impinges on my view. Perhaps for me and many others who drive this route, the gap in our knowledge about this problem will wash over us each time we pass over the water.

Sue Burwell

Cudahy, WI

When you stand in the doorway to our church kitchen and the doors to the parish hall are propped open, you can kind of see and hear what’s going on in the sanctuary. There is a gap, and you can hear the organ, the hymns, and the low, comforting hum of the liturgy. Recently I was on the hospitality committee for our annual All Saints potluck, along with my mother and my godmother. But on the day of the potluck my godmother was pulled away by a family emergency. Apologies to Mary, but we had a Martha moment in front of us and, as if possessed by generations of church women who had come before us, my mother and I set to work.

As we waited for yet another dish to heat up, I found a brief moment and went to stand in the doorway of the kitchen. I could hear the sounds of a familiar hymn and see people I love singing together from the old blue hymnals. Worshiping together. Taking the time out of busy weekends to gather together to take part in something bigger than themselves. Something must have shown in my face, because my mom looked at me questioningly. I said, “Do you ever think about what a miracle church is? That all of us are here together?”

I’ll be honest: I don’t always want to go to church. I get annoyed losing time on my weekend when I could be having brunch with friends or at home in sweatpants. At 32 I’m too old to go to church hungover or exhausted, so I can’t stay out too late on Saturdays. I have laundry to do. Books to read. Errands to run. I sigh when I realize there are long lectionary readings that will delay my return home by a few minutes. I resent the time it takes to be part of my faith community by volunteering and staying for coffee hour.

But somehow, as I stood in that doorway, the literal gap between the worship service and me helped me remember what a miracle church is. That we do give up the valuable free time we have to gather together in communion. To wonder at the unknowable. To be part of a community in an increasingly divisive and alienated time. To eat delicious food. As we transferred casseroles out of the ovens, my mother and I talked in hushed tones about my great-grandmother, who had been a missionary when she was my age and had written about how despite her homesickness she felt connected to others through faith. The gap between her and her family, a gap that spanned oceans and continents, disappeared as she remembered love and faith while preparing communion under the stars.

After the service a couple dozen people flooded into the small parish hall, and I was suddenly very busy and very much in the middle of things. Keeping the coffee carafes fresh and filled, taking empty dishes back to the kitchens, watching in low-key horror as someone used the wrong tongs and contaminated all the gluten-free desserts. I wiped up spills. I answered questions about my godmother’s family emergency. I helped somebody make a plate for a housebound member and they ran it across the street.

To be part of this community, united in our belief in something bigger than ourselves, is worth giving up my Sunday mornings. I had been too close to remember that. I needed a small gap to remember why I do this. I needed a few feet of distance to remember that church is worth going to bed early on Saturday night for.

Frances King

Hillsboro, OR