Djokovic against the gods

Humans crave stories that create order, whether they’re about the supreme being in the universe or the greatest tennis player in history.

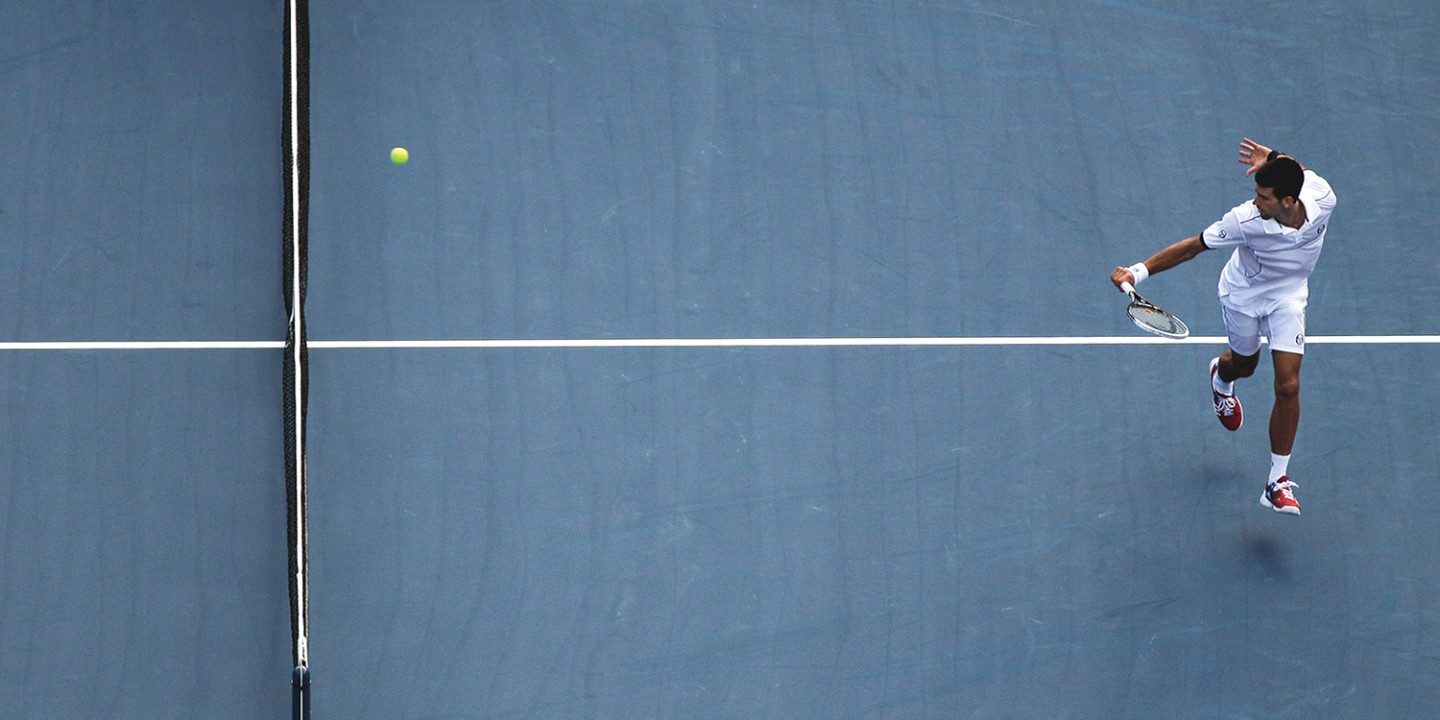

Novak Djokovic, of Serbia, returns a shot during the 2011 US Open tennis tournament in New York. (AP Photo / Charlie Riedel)

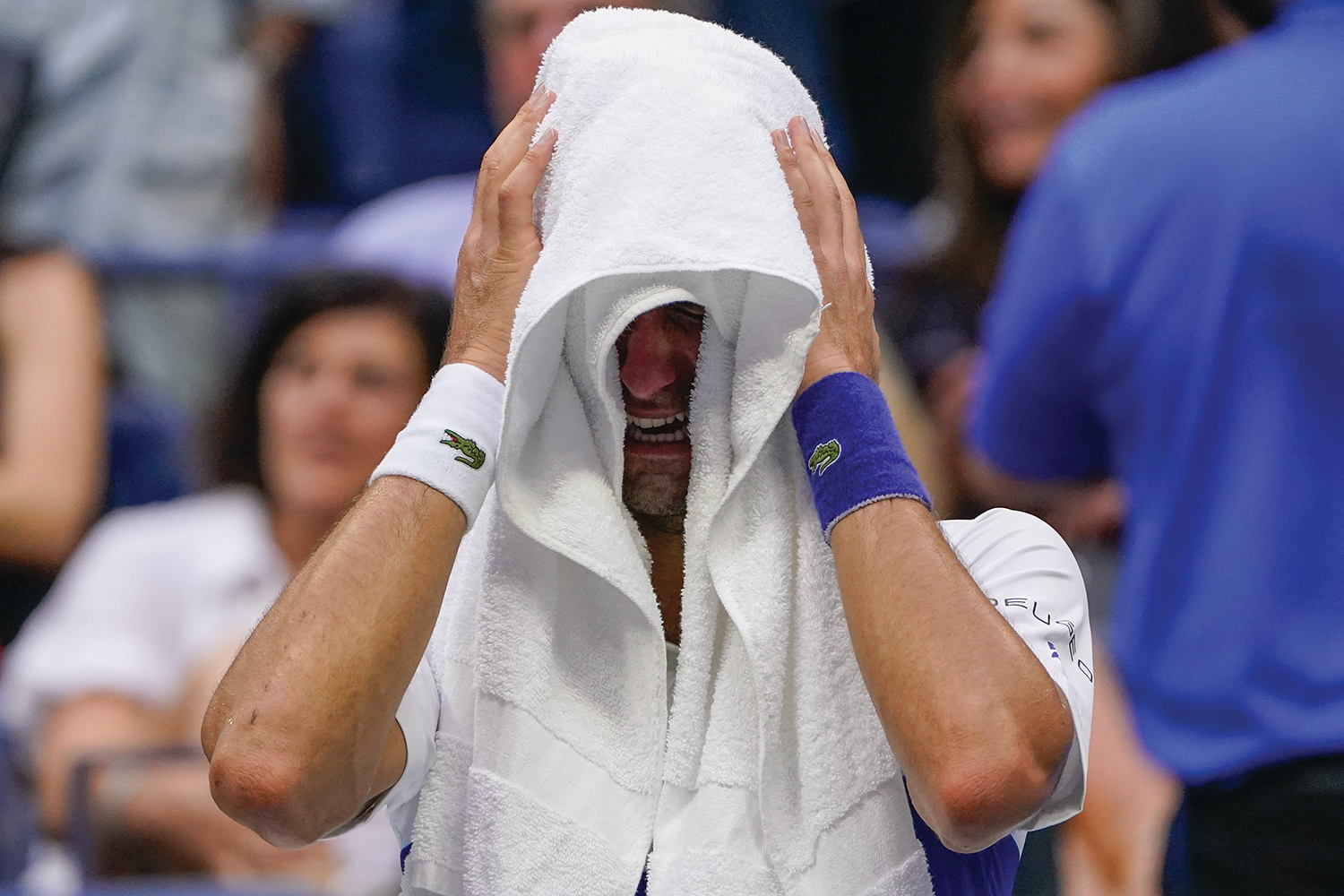

Novak Djokovic cries during a changeover in the 2021 US Open men’s singles final against Daniil Medvedev. (AP Photo / John Minchillo)

It’s 2011, and Novak Djokovic, to great fanfare, is about to lose.

The Serb stands one inch tall at the bottom of my friend’s cracked laptop screen. Opposite him, the Swiss great Roger Federer readies himself to serve, his left hand rising as his body arcs into a form as familiar as classical architecture.

Federer’s toss, as ever, is perfect. Up five games to three in the final set of the US Open semifinals in Queens, New York, he is winning the game 30–15, two points away from dispatching Djokovic and giving the crowd what it desperately wants: a storybook final between Federer and his consummate rival, Rafael Nadal of Spain.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Djokovic has already established himself as one of the all-time great returners of serve, but this one fools him, landing short in the service box and kicking even farther right than usual. Djokovic’s usually devastating two-handed backhand finds the top of the net and falls back onto his own side.

The crowd at Arthur Ashe Stadium explodes in a roar—a somewhat atypical response to an unforced error. Then again, this error has left Flushing Meadows one point away from hosting the next chapter in the greatest rivalry tennis has ever seen.

At this point in 2011, Federer and Nadal have won a combined 26 majors—16 for Federer to Nadal’s 10—and it is not just their victories that bond them. The two men seem to have been prefabricated to compete with each other: Federer the aesthete and purist versus Nadal the spartan brute. Righty against lefty. Attack versus defense. Virtuosity against will. David Foster Wallace, in his classic essay “Roger Federer as Religious Experience,” describes them as Apollo and Dionysius.

The pair’s titanic clashes in the 2008 Wimbledon final and 2009 Australian Open final (both won by Nadal) left crowds hungering for Federer’s opportunity for redemption. The storyline is one heroic triumph short of a perfect plot, and nine miles away from the stadium, I pound my fists into a bare twin mattress, willing Federer on to his destiny.

I’ve been crashing at my friend Chris’s dilapidated Brooklyn apartment the past few days, so close to Queens that I can almost feel the reverberations of the crowd. Chris is an old roommate of mine, a former college athlete like me and interested enough in the match to have spent the afternoon driving his fingers through his hair or burying his face in his palms as the pendulum of momentum has swung back and forth. I like to see him so invested, to know we still share at least this from our former life.

Our alma mater, a pristinely kept evangelical college in Middle America, feels a world away from Chris’s grimy neighborhood a handful of subway stops beyond the cool parts of Williamsburg. At school we bonded over our love of sports (he a soccer player and me, tennis) but also our interest in the arts (painting for him and writing for me). We each grappled with a sense of cognitive dissonance between our lived faiths and the God of mandatory chapel services, but after leaving my faith early in college I followed a trajectory back toward it, far enough to wind up at a seminary in Chicago. Chris followed a very different trajectory, struggling enough with his faith to tell me on this visit that the God of our old campus makes little sense to him now. “How can we really know,” he asks, “who the real gods are?”

After missing the return, Djokovic strides to the deuce court as if it is the final errand on his to-do list before heading for the airport. Most players, Djokovic included, would typically use the provided towel here to dry their face and forearms, mentally resetting before the impending match point. Instead, Djokovic walks directly toward the spot where he will face what is arguably Federer’s most devastating shot: his first serve.

Halfway there, though, Djokovic’s stoic expression breaks. With the crowd roaring down at him, his mouth contorts in a haughty smirk, and his head bobs in a sardonic acknowledgment that, of course, the crowd’s biggest outburst of the afternoon is for his failure.

Djokovic has earned this moment of petulance. At 24, he has proven himself the most consistent challenger to the hegemony of Federer and Nadal. He is no upstart. In fact, to this point in 2011, he has logged one of the most successful calendar years in tennis history, having won two of the year’s first three slams, capturing the world no. 1 ranking for the first time, and amassing a ghastly 9–1 calendar-year record against the two giants.

Perhaps the crowd’s fanatical cheering belies some of these statistics. Perhaps they, too, sense a threat, and so they roar on. People have been buzzing about how, unlike the other three majors, the US Open has yet to witness a Federer-Nadal final. I’ve already promised myself that whatever loan I have to take out, whatever hours I have to spend haggling outside the stadium, I will find a ticket for such a final. Lying on a mattress in Brooklyn, nine-tenths of my pilgrimage is already complete.

Federer arrives at the baseline ready to make our collective dream a reality. As he dabs sweat from his brow with his wristband, he steals a quick glance up at the crowd, gauging how long it’ll be before it’s quiet enough for him to serve his way into the final.

Across the net, Djokovic still wears a knowing frown as he bends into his return position, his upper body swaying left and right, his lips pursed and chin nodding as if to say, OK, world, so this is how it is going to be. It’s an expression that has never, ever, crossed the face of Federer or Nadal in a grand slam semifinal. But it will come to epitomize the man Djokovic in his war against the gods.

Federer bounces the ball four times before launching into his architectural motion. Match point. Camera shutters clatter like muted gunfire. The strike of the ball is pure, but long before it bounces Djokovic has correctly surmised both that the ball is going wide to his forehand and that Federer has missed his spot. Instead of curling untouchably away, the serve misses its target by ten inches or so—a wide margin by tennis standards—and Djokovic will have a play on it.

What happens next is an act of utter defiance, a 90-plus mile-per-hour fuck you of felt, piss, and vinegar that hurtles back across the court so fast Federer doesn’t bother moving for it, barely even watching it before it slams into the wall after bouncing a second time. Improbably, the first bounce has found the court. Tennis history, viewed backward in the light of the decade to come, has just been rewritten.

The defiance of the blow is not exactly directed at Federer, although it is not not directed at him—something like the way a teenager, furious at his parents, vexes a sibling by overturning the dinner table. The gesture is in Federer’s direction, but really it is aimed past him, at the 23,000 fans who are ravenous to see Djokovic lose. It is directed at the thousands of media questions Djokovic has answered throughout his career that have begun with, “Given what Federer and Nadal have achieved . . . ”

It is directed at me.

I am, in 2011, still a believer, still convinced that Federer is the best tennis player ever to walk the earth, still eager to see him prove this by solving the riddle presented by his perfect foil, Nadal. Their recent matches have carried an air of inevitability, and not in Federer’s favor. But the overall numbers are still mostly amenable to my position. In addition to Federer’s record 15 grand slam singles titles, he holds a litany of other records that even Nadal, newly formidable across all court surfaces, seems hard-pressed to overtake.

By the time Federer reaches his towel, though, everything seems destabilized. Djokovic heads for his towel, too, and 20 feet away the crowd is just beginning to come out of a stunned stupor. Whistles turn to cheers turn to a roar. Djokovic, in so many ways aberrant from the self-mastery of his two elders, raises both arms to the sky, his hands open and calling for affection, for affirmation, for recognition of the deicidal blow he’s just struck. The crowd reacts, many in shock but some in glee, perhaps because they love Djokovic but more likely because it means the drama before them will continue.

The plot, in a way specific to great tennis matches, has thickened.

Aristotle famously defined story as “that which has a beginning, middle, and an end.” Within this seemingly pedantic definition hides something crucial: order. Augustine would later describe this function of storytelling as the triumph of concordance over discordance. Stories, by the very nature, organize. They take randomness and make a whole.

Back at my Chicagoland seminary, I’ve been preparing to write a thesis about the relationship between narrative and theology, drawing from the work of literary theorist Frank Kermode. Kermode agrees that stories provide order, but he adds an important caveat: the organization they provide is often a kind of lie. We use stories to foist order onto a fundamentally chaotic world. The story of Christian orthodoxy is his preferred example. Humans long for order, so we create stories that provide it—whether those stories are about the supreme being in the universe or the greatest tennis player ever to play the game.

A whole section of the crowd beside Djokovic stands, clapping, and he gives them a smile before his raised hands drop to his sides, his head shaking in disbelief that it takes the shot of his life to elicit their support. What must I do, he seems to be saying, to earn your love? He tries to swallow the grin, but after he bends into his return position it resurfaces. Still down match point, still one serve away from walking out of the stadium a loser, he is smiling. Federer glances across the net at his grinning opponent, and the cold look on his face—glowering, by Swiss standards—lasts only a moment. But Federer is rattled.

So rattled, in fact, that Federer will lose 16 of the match’s remaining 20 points, littering the next four games with errors. Fifteen minutes after Djokovic’s fateful return, it will be Federer walking off the court a loser and Djokovic staying to field questions in the post-match interview.

The interviewer asks Djokovic—impertinently, it seems to me—what he thought of the crowd, adding that she felt he got more support after his rocketed return. “The crowd was great . . . so loud,” he says, lying. At best, this is a willful misremembering of a crowd that, 30 minutes earlier, had been cheering his missed serves and errant returns. At worst, it is a tactical lie by a man who has not yet given up hope that someday the crowd will love him the way it loves Federer and Nadal.

Twenty-four hours later, the crowd will begrudgingly cheer as Djokovic hoists the US Open trophy, leaving Nadal to ponder a stunning sixth consecutive loss to Djokovic in one calendar year. The cheers will be muted, because Djokovic’s wins have prevented New York from celebrating what, two days earlier, had looked likely to be another chapter in the greatest tennis story ever told.

In truth, Djokovic’s win threatens that storyline in its entirety. The thoroughness of Nadal’s defeat makes it hard to imagine a world in which Nadal and Federer can retain relevance, let alone the dominance they’ve enjoyed in recent years. And by the time Djokovic hoists that silver cup, I am back in Chicago, no loans taken out, disappointed but still hopeful that Federer and Nadal will have time to re-stake their claims as the true gods of tennis.

Djokovic gives the crowd a smile before his raised hands drop to his sides, his head shaking in disbelief. What must I do, he seems to be saying, to earn your love?

It’s 2019, and Novak Djokovic, to genteel fanfare, is about to lose.

Nothing could’ve prepared us for what’s transpired since his blistering shot in Queens. Despite a long tradition of tennis players retiring in their early thirties, Federer, age 30 in 2011, was in fact squarely in the middle of his career. Nadal, despite his physical play style, was not even halfway through. And Djokovic, of course, was just getting started.

Eight years later, Djokovic and Federer have found themselves locked in another battle of epic implications. The two men remain at the top of the game, their legacies ever more in focus. This time the setting is not a raucous blue-and-green American hard court but a picturesque English lawn. Again, Federer has played his way into an opportunity to serve out a fifth and final set, this time in the Wimbledon final. Again, the crowd is far from impartial, yearning for Djokovic’s demise.

The Big Three—they are now, undoubtedly, three—have spent the intervening years pushing one another to dominate their shared competition longer and more thoroughly than any trio in tennis history. The three men have won 53 of the 63 grand slam tournaments since 2004. While each of them has suffered setbacks and had seasons of resurgence, other players have simply failed to keep pace. The final rounds of slams have become tales of the matchups between the Big Three, each with its own storylines and mini dramas.

In 2017, for instance, a resurgent Federer defeated Nadal to win the Australian Open, finally breaking through Nadal’s relentless barrage of high-rpm forehands to Federer’s one-handed backhand. It felt miraculous seeing Federer step in and attack with his backhand, utilizing a bigger racquet he’d recently switched to, and finally solve the cosmic riddle presented by the fates in the form of Nadal. The collective 2011 hopes for a Federer triumph were reborn as Federer went on to win—at ages 36 and 37—three of the next five slams, again putting some daylight between his legacy and those of Nadal and Djokovic.

But it was undoubtedly Djokovic who set the standard across those eight years, finishing five times as the year-end world no. 1 and greatly closing the gap in grand slam titles between himself and his two almost peers.

And yet, here at Wimbledon in 2019, through five sets spread across a lovely English afternoon, a neutral observer would never guess that Djokovic is the current world no. 1 and defending Wimbledon champion, so intensely is the crowd backing Federer. They applaud Djokovic’s best shots, but they shoot out of their seats each time Federer crosses a threshold separating him from his record ninth Wimbledon title, each time he looks more certain to extend his record 20 grand slam titles, outpacing Nadal’s 19 and Djokovic’s 17.

Today, at 8–7 in the fifth set (the tennis equivalent of overtime) with the score 30–15, Federer slices yet another ace up the center line past a lunging Djokovic. He’s now one point away from a career-defining victory, despite all the trophies already in his possession. He’s again beaten, in incredible fashion, his foil Nadal in the semifinal to get here. He’s outplayed and outcompeted Djokovic over what has already become the longest final in Wimbledon’s history. And now a single stroke lies between him and not just immortality but perhaps a throne of his own as the Zeus of tennis mythology.

Now it’s 40–15. Federer’s wife, Mirka, rocks back and forth in obvious distress at the edge of the player’s box, unable to bear how thin the veil is separating her husband from the promised land. His graceful service motion delivers another perfectly struck ball. As in the 2011 semifinal Djokovic anticipates a serve out wide on the deuce side. But this time his guess is wrong. Federer’s mercurial serve is headed up the center line, and Djokovic is powerless when he realizes his mistake. The ball hurtles toward the open court as both men, the crowd, the royal box, the heavens watch it travel along its arc.

Perhaps it is no coincidence that stories, like tennis balls, follow an arc. Perhaps our inclination to look to sports for meaning and purpose is connected to how sports and stories both remind us of our limits. For all the flights of imagination of which we are capable, we are embodied creatures. Our bodies bring us back to earth. Our stories carry us beyond.

Kermode argues that stories bend events into shapes that satisfy our need for order. We assign beginnings, middles, and endings so as to give our stories a clear and obvious resolution. The Bible gives Christians an arc like this. Believers are situated in medias res between the story’s straightforward opening (“In the beginning, God . . . ”) and its promised ending. This structure imparts meaning to Christian lives by allowing them to hang like clothespins between the poles of a cosmic story. However insignificant a clothespin may seem, it remains, crucially, connected to those poles.

We are most satisfied when our stories pit our heroes against some great obstacle—Christ against the devil, Rome against Carthage, Federer against Nadal—obstacles against which our hero either succeeds (a comedy) or fails (a tragedy). But all good stories have a resolution of some kind. Federer, age 37, avenges his epic 2008 loss to Nadal. Unfortunately for the story of their rivalry, it comes a round too early, in the Wimbledon semifinal, and here in the final he still is pursuing vindication, the ball suspended in midair and his status as the GOAT suspended with it.

The arc of Federer’s serve on championship point bends one inch too sharply, clipping the white tape at the top of the net and dying on his own side. Djokovic shakes his head in relief. Mirka Federer buries her face in her palms. She is right to feel torment: devastation is coming again. Federer will lose this point and soon the game, and just like that, one incredible story of tennis greatness will become a subplot in another.

This time there is no petulance from Djokovic, though the crowd is ever more unabashedly rooting for Federer. And from Federer, there is no glowering look, no competitive withdrawal. Instead each man plays a handful of masterful games to prevent the other from running away with the title, and it is only after a fifth set tiebreaker—the first in Wimbledon finals history—that Djokovic finally bests Federer and walks calmly to the net to shake his elder’s hand.

The English crowd, polite as it sounds, is gutted. Federer is gutted. And Djokovic, despite his herculean victory, is gutted, as he has always been, that his greatest triumph means the crowd’s greatest disappointment. He is powerless in the face of a better story. His triumph is simply not the ending the crowd has come to see. Their hero’s redemption has been dashed by a villain who seems borrowed from another story entirely.

That villain squats, pinches a snippet of the immortal English lawn, and chews it, as has become his custom after his six Wimbledon championships. The crowd applauds dutifully, but there is no mistaking the familiar sardonic grin that washes over his face as he chews, as if all he can hear are the imagined roars that would be issuing through the All-England Club if Federer, the crowd’s true champion, had defeated him.

One operating assumption of Christian orthodoxy is that all stories are presided over by a God who, even if beyond our understanding, holds the final truth of any given matter in his hands. Implicit within Kermode’s argument is that no such God exists. That this God—the GOAT of all GOATs—has been a figment of our collective imagination all along, a by-product of our need for order. Jean-Paul Sartre describes life after God as a state in which “existence precedes essence.” There are no ultimate stories from which to glean our rightful role in the world. Each of us is condemned to choose a narrative for ourselves.

Djokovic is about to do exactly that. In the post-match press conference, he describes how he spent the match imagining that he could will the crowd’s thundering “Roger, Roger!” chant to morph into “Novak! Novak!” But there are also indications that this wishful posture is changing. That if the crowd doesn’t want him—if he is not a part of their story—then to hell with them. He will compose a story of his own.

One operating assumption of Christian orthodoxy is that all stories are presided over by a God who holds the final truth of any given matter in his hands. Implicit within Kermode’s argument is that no such God exists.

It’s 2021, and Novak Djokovic, despite great fanfare, is about to lose.

At age 34, Djokovic has dominated the year’s tennis calendar more completely than either of his two great rivals ever did. The calendar slam—winning all four of the year’s grand slam titles—is the rarest of tennis achievements. No player has been a perfect four for four since 1988, when Steffi Graf managed it (along with a gold medal). Neither Federer nor Nadal ever even reached the US Open (the year’s final slam) with the opportunity intact. Djokovic, a few hopeful hours ago, entered this final match of the US Open as a heavy betting favorite.

Nothing about today, however, has followed the script.

A year after a global pandemic shuttered professional tennis for much of the 2020 season, the stands of Arthur Ashe Stadium are full again, and for perhaps the first time in Djokovic’s career, the crowd at a grand slam final is desperate to see him win. They chant his childhood nickname—Nole! Nole! Nole!—while he sits on his player’s bench, despondent.

He is four points away from a stunning, straight-set loss in the biggest match of his life. The same crowd that has so many times broken Djokovic’s heart is doing everything it can to revive him. Djokovic drapes his towel over his head; his shoulders begin to bounce. All at once, it becomes obvious: Novak Djokovic is weeping.

Neither of his two great rivals is responsible for the tears he is hiding beneath his white towel. In fact, neither played this tournament at all—both are convalescing thousands of miles away.

Federer, in what many feared was his last competitive match, finally looked old in a lopsided quarterfinal defeat at Wimbledon two months prior, undergoing yet another knee surgery soon after. But it was Nadal’s loss to Djokovic at the French Open that was truly devastating. Nadal grabbed an early lead before something changed at the end of the third set. There were no histrionics from Nadal about an injury, just a grimace and a quick look to his box. But watching him silently fume, knowing that a tiny bone in his foot would ensure he could not prevail on the court he’d owned for a generation, felt like a contradiction in terms. It felt like watching an immortal die.

The title of Kermode’s book The Sense of an Ending speaks to its thesis: that a story’s ending comments on its beginning and middle from a privileged position. A story’s ending, that is, tells you what to think of the rest of it. But Kermode’s point is that life is not actually like this. We don’t know if we’re in the beginning, middle, or end of any given story—especially our own—and we don’t get the benefit of knowing, as a novelist might, how to arrange our lives in advance so as to make sense of the ending.

The same is true of athletic careers. No one in 2021 believes that this will be Djokovic’s final opportunity to break the grand slam deadlock between the Big Three, and they are right. In the years to come, Nadal and Federer will slowly find their aging bodies forcing them out of competitive tennis while Djokovic races out ahead of nearly all their once seemingly unbreakable records.

Thirty feet away from where Djokovic is trying to regain control of his emotions, his young Russian challenger, Daniil Medvedev, stares madly ahead, chomping on an energy bar as if it contains the secret to serving out a major championship against Djokovic. Just before the chair umpire calls the players back on court, a wet-eyed Djokovic takes a deep breath, gazes lovingly up into the crowd, and taps a hand over his heart. He smiles and pumps his fist, sardonic malice nowhere to be found. The crowd roars its approval.

I watch all this unfold from my living room couch. I haven’t exactly been rooting against Djokovic, but I haven’t really been able to cheer for him, either. I want to see this history made; I just never wanted him to be the one who made it.

My four-year-old son, nestled in the crook of my arm, asks me which man is my favorite. My favorite players, I tell him, aren’t playing today. The best player is, though. The best player is about to lose the biggest match of his life. My son is confused, and I tell him that he’s right to be—that sometimes stories end in ways that frustrate or confuse us.

A few points later, a punishing serve from the Russian elicits a final, ill-fated stab from Djokovic. Game, set, match, Medvedev.

A strange sensation washes over me: a fog of disappointment and relief. Djokovic has lost, but I feel the inevitability of his future. He will soon relegate my tennis heroes to roles for which they never seemed destined: a pair of foils who spurred the best tennis player of all time on to greatness.

What can I say to my son as he asks me if it’s over? In a way, yes. One story’s ending spawns another’s beginning. I think of my friend Chris, whose painting career, like my writing career, hasn’t followed the narrative arc we once dreamt of in our 20s.

Gnawing at me, though, is Kermode’s question: Aren’t all our stories really just meaningful lies? Consolations that mask an unbearable truth? Or do the stories we tell—and our inclinations to storytelling—signal that we belong to a more transcendent story? Who among us—Federer, Nadal, Djokovic; me, Chris, my young son—doesn’t dream of touching greatness?

Djokovic embraces Medvedev at the net, graciously congratulating the first man born in the 1990s to wrest a grand slam title from the hands of the Big Three. Djokovic will cry again during the trophy ceremony, saddened by an opportunity missed but also undone at finally being cast—despite the loss—in tennis’s leading role.