The great man theory is poison for the church

The problem isn’t just that it exists. It’s that so many ministers fall for it.

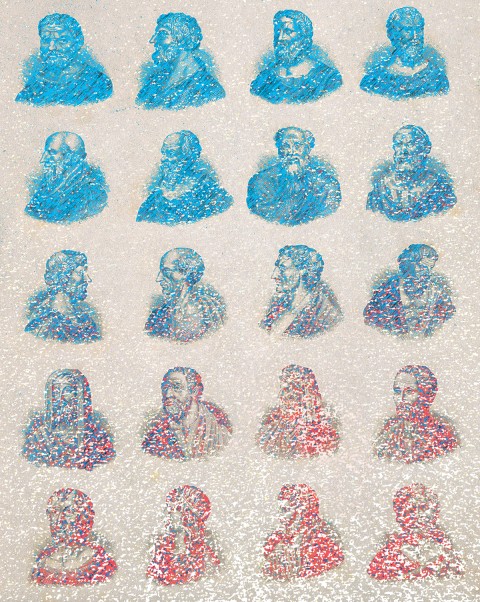

(Century illustration)

There’s a lot we still don’t know about clergy burnout. People used to think of it as a product of time—even the best engine will break down after too many miles—but then the many examples of good, effective, older clergy helped to settle that ageist assumption. It has also been described in terms of damage: some traumatic event takes place, whether during one’s ministry or before, and it decreases the lifespan of that ministry. But while I don’t want to discount the impact of trauma, the corresponding implication—if nothing happens, I’ll be fine—is troubling. Because stuff happens all the time! Each of us lives with a lot of stuff, and I’d hate to think of caring for ourselves as simply maintenance to help us last longer. We’re humans, not Toyotas.

I think burnout—and the health of churches and ministers generally—is less about what has happened and more about the assumptions we bring to this holy work in the first place. And the more I talk to my millennial and Gen Z clergy colleagues, the more I’m certain that one particular assumption is going to be our ruin. It is called the great man theory, and while it has roots in Plato, it really comes from Thomas Carlyle. “The history of the world,” said the 19th-century Scottish philosopher and polymath, “is but the biography of great men.”

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

And so the theory goes: human innovation is essentially stagnant until truly special people come along and push us forward. Look at Plato, Newton, Napoleon, Shakespeare, proponents of this theory proclaim. The history of the world is told through a few special humans—the Founding Fathers and Albert Einsteins and Martin Luther Kings among us who broke through the ice of mediocrity. And the fact that our schools teach history like this (the story of America, for example, as one about the brilliance and resilience of a few individuals instead of colonial conquest and genocide) is one way we communicate to our children that this is what they should become: Great. Singled out. Special. Change makers. Then when most of them don’t—because this theory is trash—our culture says they didn’t make it and lifts up the ones who do ascend, forgetting the rest altogether.

I wish our religion had more to say about this, but often it doesn’t. In fact, we participate in this scandal against humanity with our hagiographies of Moses and David and Paul, with our stories of people told through prophets. And of course we have at the center of our Christian faith the story of a man who apparently the entire past has led to and any meaningful future will flow from, even though he wanted nothing to do with being singled out. Seriously: I’d be shocked if Jesus wasn’t a little irritated by the fact that we count time according to when he lived on earth. It’s embarrassing, for him and for us.

Often we either see ourselves as special or don’t see ourselves as having a place at all.

So it’s no surprise when congregations struggle with collaboration, whether internally or with other churches and organizations. If we don’t see ourselves as special, we tend not to see ourselves as having a place at all. Instead, our goal is to “find the right person.” The special one. Many of our congregational histories are told not as eras of movement but as a list of previous pastors. When things were going well, it’s because we had a good pastor. And when they weren’t? Well, that pastor wasn’t special.

The primary problem is not that the great man theory exists—even that it exists in the church should come as no surprise—but that we ministers fall for it so often. So many of us see our work not as part of a great collective that spans time and place but as my work to do. We spend a lot of our time trying to be the one who got it done, to be special. We think about what innovation we’ll bring, about what our legacy will be. We fall for this great person stuff, and instead of telling people that’s not what they should be looking for—you know, like Jesus did—we spend more and more of our resources trying to become the next one.

It takes a lot of energy to pursue greatness. Burnout seems inevitable.

If we could instead turn away—repent, even—from heroes and rock stars and great man nonsense, we could move closer to health—and closer to the gospel. In the history of our world and our faith, the truly great ones are those who do nothing more than respond with courage and curiosity to whatever is happening. In trauma or in privilege, our God expects us to respond faithfully.

We have to stop looking for greatness or trying to be that for others. We have to stop trying to be the next or the first. Let us pursue excellence, by all means, but if the history of the world is nothing more than the biographies of great men, we’re doomed—and so few of us mean anything. Resurrection tells a different story altogether: a story of people whose God is great and whose blessing belongs to each of us to share and act out together.