Carlton Minnick, influential UMC bishop, dies at 96

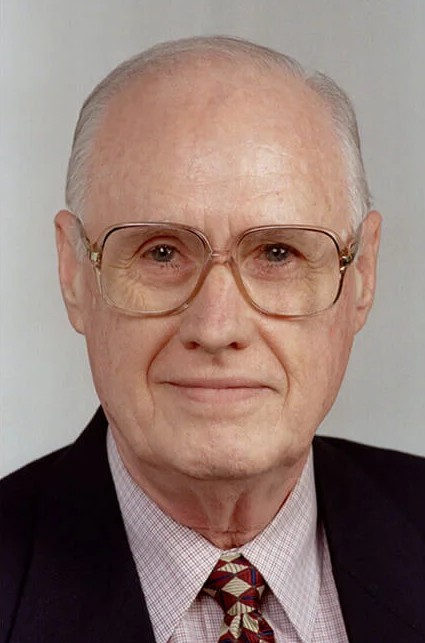

Carlton "C.P." Minnick. (Photo by Mike DuBose, United Methodist News Service)

Carlton “C.P.” Minnick, a former president of the United Methodist council of bishops, died May 4. He was 96.

Minnick led UMC conferences in Mississippi and North Carolina, and he became known for championing women in ministry and helping lead the council of bishops to speak out against US nuclear weapons policy.

“His leadership style was marked with openness and grace,” said Belton Joyner, Minnick’s assistant in the North Carolina Conference. “It was clear what he felt but he had room in his heart for relationships with those with whom he did not agree.”