What can Biden do without cooperation from Congress?

Lots of things. Here are a few priorities.

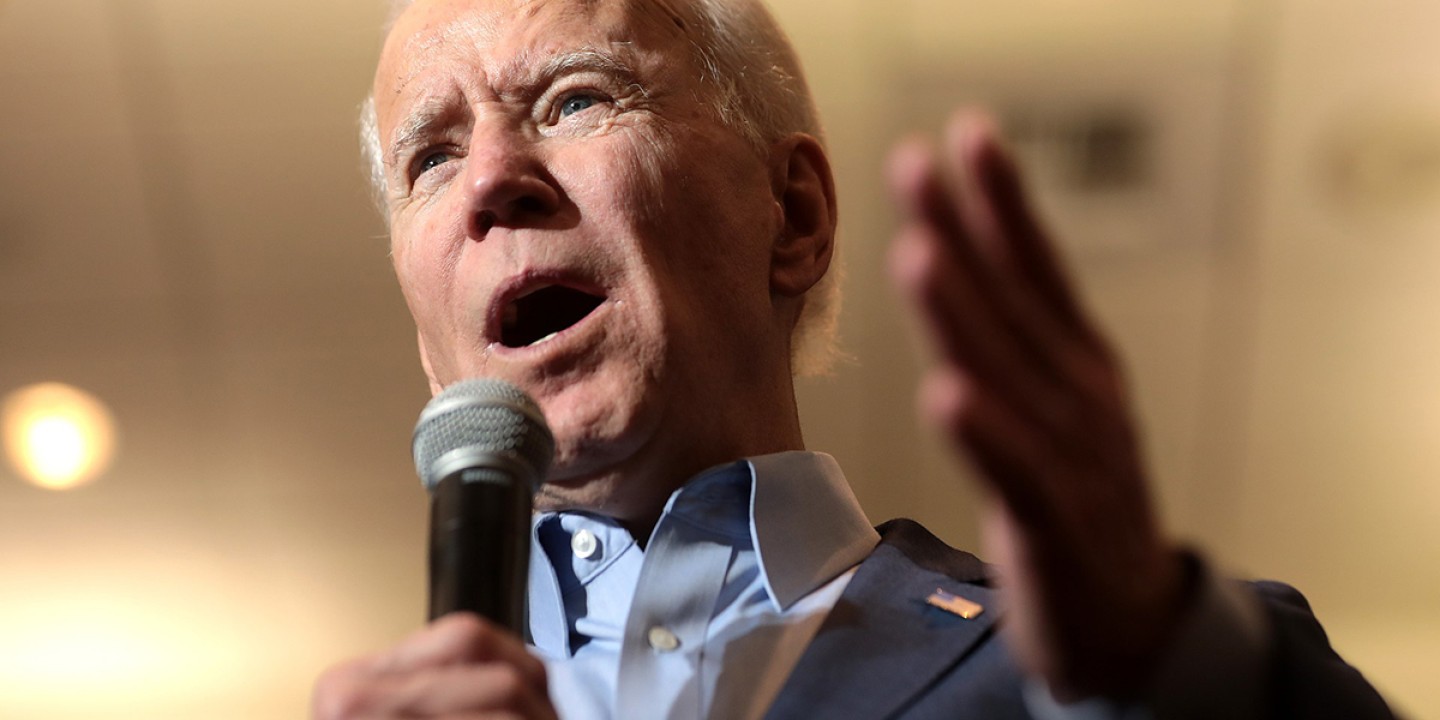

When Joe Biden takes office as president, he’ll have plenty to do. The United States faces numerous pressing, even urgent challenges. At press time it was not yet known which party will control the Senate or whether any modicum of cooperation between branches will be forthcoming. But there are many things the Biden administration can do quickly and without Congress’s help. Here are some top priorities.

Establish a robust federal COVID-19 response. So far, public health guidance has been confusing, contradictory, and politically compromised. Governors have found themselves in bidding wars for medical equipment. While vaccines are now being produced, states need assistance and funding to distribute them effectively. Biden can’t undo the harm of months of weak governance, but he can change course.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Recognize the rights of asylum seekers and refugees. Biden can act quickly to keep families together, to stop deportations without due process, and to allow asylum seekers to make their case from the US side of the border. He can increase the cap on refugee resettlement. And he can halt construction of the costly and pointless border wall.

Rejoin the Paris Accord. While the pandemic crisis took center stage in 2020, the climate crisis never went away. The 2016 agreement doesn’t go far enough, but it’s an important step toward addressing climate change in a globally coordinated way. The United States pulled out in 2019; a new administration can get us back to the table.

Nurture global relationships. The last four years have hurt American standing in the world. American dominance of old was not entirely a good thing, and there is little point in trying to reclaim it. What Biden can do is work to rebuild networks of cooperation, trust, and mutual respect.

Reinforce the missions of federal agencies. Public health officials are not the only career government employees who have been marginalized by political appointees. It’s happened across the executive branch—and while a new president might be tempted to quietly embrace this trend and shape it to his own ends, Biden can and should reverse it instead.

Some of these efforts will depend on executive orders, which the last two presidents relied on heavily. No doubt Biden’s opponents will criticize him for doing the same. It isn’t democratic, they’ll say; it has no checks and balances.

In theory they’re correct. Policy should be enacted by Congress, with the president’s input and eventual signature. But that system has been rendered dysfunctional, overwhelmed by its structural weaknesses and by the powerful incentives of partisanship. Gridlock now reigns until one party wins the White House, a majority of the House of Representatives, and a supermajority of the Senate—or until democratic reforms are enacted to change this bleak status quo.

In the meantime, executive action is often the only viable action. In a time of great crisis, it would be irresponsible for Biden not to use it.

A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “A to-do list for Biden.”