God became flesh, but he never had breast cancer

I was diagnosed just after Christmas. It changed my perspective on the incarnation.

On the second day of Christmas, during a painful biopsy on my left breast, I realized that I wasn’t fully on board with the incarnation. In the Episcopal Church’s lectionary, the Gospel reading on the first Sunday in Christmas is John’s prologue: “the Word became flesh and lived among us.” It’s one of the most beautiful doctrines of the church: God became one of us, with a body. I preached on that reading, about God becoming flesh and living among us, but I didn’t want my parishioners to know that I have flesh—specifically, breasts.

Clergy wear long, flowing robes over our clothes so people won’t focus on our bodies. The only thing harder to contemplate than telling my congregation that I might have cancer was that it was breast cancer. When God became flesh and lived among us, God didn’t have breasts.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

I’m not the only female pastor who doesn’t want my congregation to think about my body. My friend Samantha has a rule that parishioners can’t ever see her in a swimsuit. But Samantha thinks I take this to extremes: I went years and years without even owning a swimsuit. My husband, Gary, and I belong to a gym with a pool and a hot tub that I won’t use. What if a random parishioner comes by? Or really, anyone—I don’t want anyone to see me in a swimsuit.

The Bible doesn’t say what Jesus wore to his baptism, but I imagine him wading into the river in a robe. He became flesh and lived among us, but he wore a robe, until Roman soldiers stripped him and hung him on a cross. Finally I found a bathing suit that looks like a shirt and shorts, but I still won’t wear it at the gym.

I don’t even want people to see me in a skirt. I have a closet full of adorable skirts: striped, polka dot, pencil. When I buy them, usually with Samantha, she asks, “Are you actually going to wear it this time?” I almost never do, and when I do, for Easter or a biannual bishop visitation, my parishioners comment that I rarely wear skirts—and I remember how, when I was a lector at a small church in Chuckatuck, Virginia, a woman told me in an icy drawl that her husband loved it when I read because he enjoyed looking at my legs. The skirts look lovely in my closet.

Do not worry about your body, what you will wear, Jesus said. To me, that sounds like a man. Women are judged by what we wear. I doubt this was different in Jesus’ day.

I didn’t wear a skirt to the biopsy. The tech pointed to a dingy bathrobe on a stark chair next to a desk surrounded by monitors. On the other side of the room lurked something that looked like a dentist chair facing a mammogram machine. After I put on the robe, which was nothing like the robes I wear on Sundays, the tech said, “I need to ask you these questions. What are we doing today?”

When people address me using the first person plural, I want to punch them. We weren’t doing anything. They were going to stick needles in me.

“Biopsy,” I replied, hoping my tone sounded withering, not terrified.

“Actually two biopsies,” she corrected me, then explained that I would be “compressed” in the scary chair the entire time. She said it shouldn’t take more than an hour.

She marked my breast with an ink pen. When a stranger touches my breast, I don’t think about God being like me. God became flesh, but not a woman. Jesus did not have breasts, judged for their size and firmness. Jesus looks pretty muscular in most depictions of him on the cross, but imagine if it were a woman hanging there topless. How big would her breasts be? Would they be firm breasts that had never nursed? Jesus said that the days are coming when some will say blessed are the breasts that never nursed, but since my breasts never nursed, I am at higher risk for breast cancer.

I knew the biopsy—biopsies—would involve needles, but I didn’t know I would be “compressed” the whole time. “Compressed” meant I had to slightly arch my back so that my entire breast was painfully pinned between two heavy, cool, clear plates, which were slowly brought together so that my sensitive breast was smashed lower, lower, lower, the skin of my chest pulled tighter and tighter, my nipple thrust farther and farther to the front of the machine. I bit the area below my lower lip until I tasted blood. “You won’t feel the needles,” the tech said.

Before they stuck the needle in, they photographed my flattened breast several times, repositioning and frowning. As the doctor, tech, and nurse took more photos, they kept telling me to lean back. “Farther.” “Farther.”

I could barely feel the big needle going in. Perhaps if I could have felt it I would have thought about Jesus being pierced, about Mary hearing that her own soul would be pierced. In any case, whatever it was that numbed my breast and prevented piercing pain could not cover up the fact that my breast was being smashed.

When they were finally finished, my blood stained the dingy robe. I was swaying when they released me from the machine. “Are you OK?” the tech kept asking.

I finally snapped, “Of course not. That hurt.”

We returned for the biopsy results on New Year’s Eve. I was sure I did not have cancer, because the nurse smiled at me in the waiting room. Then we were in the office, and the doctor was frowning and saying, “The calcifications were harmless, but the other spot of concern contains a cancerous tumor.” She kept talking, but I didn’t hear anything else.

Gary asked questions and nodded at certain points and looked smart and handsome while the nurse handed me a tissue. I would have skipped a mammogram that year, convinced that they were unnecessary screening procedures that led to false positives. I only went because he nagged me. If I had not gone and the cancer had progressed and I had died, he would have been even bossier with his next wife. I couldn’t hear anything they were saying; I just watched Gary’s face.

They didn’t have a trash can in the room. The nurse offered to take my tissue as we left, but I declined because that’s disgusting. When I was a chaplain intern in a hospital, we were taught, “If it’s wet and not yours, don’t touch it.” Nurses have to touch other people’s wet messes all the time. Chaplains just hold their hands and pray. Both involve touch. Flesh. Incarnation. But chaplains get to be cleaner.

I followed Gary to my car, and even though I had driven to the hospital, I got into the passenger seat. Gary told me I needed to call our insurance company to ensure that the surgeon to whom they had referred me was in network. We argued about this as he turned left from the right-turn lane leaving the hospital, the only indication that my diagnosis had affected him. I pointed out his error as cars honked at us, but he insisted that he had not been in the right-turn lane. I asked why he wouldn’t call the insurance company his damn self, seeing how his wife had cancer, and he told me, gently, that by doing it myself I would gain some control. “You need some control,” he said.

Pressing numbers to reach a person at the insurance company while hearing again and again on the recording that I should use their website, I thought, This is my life now. I would spend the rest of my life on the phone with insurance companies. No, with this insurance company, because no one else would ever offer me insurance again because I had cancer. I was no longer a healthy person.

I had to get my husband’s social security number because, even though I am the rector of a parish, to the insurance company I would only be the military member’s dependent. I would have to finally memorize his social security number, after 23 years of marriage, because I would have to give it again and again. I had to ask the woman on the phone to repeat things because I couldn’t understand what she was saying. She spoke in a bored monotone. This was what she did all day: talk to people about their insurance. Rather than becoming frustrated, I needed to be grateful that I had insurance. I should have felt privileged. I did not.

After finally confirming that the surgeon was in network, I was about to hang up when she said, “Ma’am?”

I was a ma’am now because I had cancer so I must be old. Being addressed as miss had always annoyed me, but now I did not like ma’am.

She was waiting for a response. “Yes?” I said, clipped. I’m skilled at sounding chilly.

“I am so sorry about your diagnosis,” she said. “But you are going to be fine. My mom and my aunt both had this, and they are fine now. You will be fine, too.”

My mouth fell open. I was not expecting kindness.

The next day, New Year’s Day, my friend Shirley took me to lunch. Shirley is also the rector of a parish and also had breast cancer. I told her how this whole situation happening during the Christmas season had me ruminating on the doctrine of the incarnation. Christ becoming one of us, with a body.

Shirley said, “Notice that Jesus didn’t come as a woman. Why didn’t he come as a woman? I’ll tell you why: periods and breasts.”

“That’s a really good point,” I said.

She added, “Also notice that he didn’t live long enough to have prostate issues like other men.”

I reflected on God becoming one of us but male, dying violently before experiencing the indignities of disease and old age. Some sneer that old age is a luxury. I wondered whether I would feel that way soon.

It was still the season of Christmas, and the proper preface for the eucharistic prayer that weekend would continue to include the words, “Jesus Christ . . . was made perfect man of the flesh of the Virgin Mary his mother.” I wondered if when I prayed these words again I would long for a less perfect man, one who had experienced disease and blemishes. If now that I had cancer, I would long for God to become, rather than a perfect man, an imperfect woman.

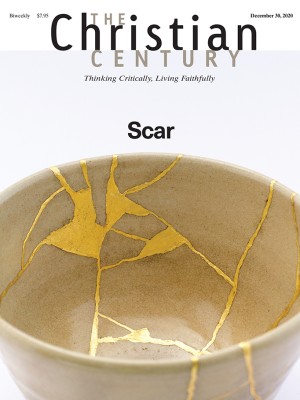

A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “Imperfect flesh.”