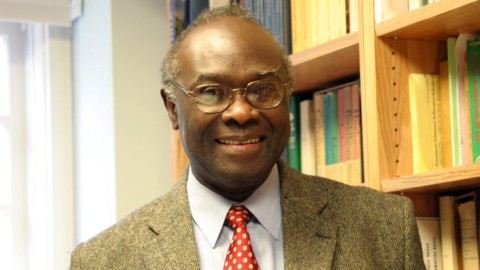

Honoring the memory of world Christianity expert Lamin Sanneh

Sanneh was a rigorous polymath who cared about not only theoretical work but the everyday lives of those who believe.

(RNS) — Lamin Sanneh, D. Willis James Professor of Missions and World Christianity at Yale Divinity School, died unexpectedly from a stroke on Sunday (Jan. 6). He was 76.

In the words of Simeon llesanmi, “An African Academic Elephant has indeed fallen”— meaning that a great individual has died.

Sanneh’s scholarly contributions spanned more than 20 books as author and editor, and over 200 scholarly articles through the course of 40-plus years of academic scholarship on four continents. He represents a particular kind of scholar that is hard to come by in today’s academy: a rigorous polymath who cared about not only the theoretical work of theology and history but the everyday lives of those who believe.

Born in Gambia to a royal lineage, Sanneh grew up as a Muslim but later converted to Christianity. Earning his graduate degrees from the University of Birmingham (M.A.) and the University of London (Ph.D.), Sanneh would go on to teach at the University of Ghana, the University of Aberdeen, Harvard Divinity School and, since 1989, at Yale Divinity School. He worked with Andrew Walls setting up World Christianity Conferences and was a member of the board at the Overseas Ministries Study Center at Yale Divinity School. He has served with extraordinary distinction in many areas, including holding a lifetime appointment at the University of Cambridge’s Clare Hall and holding the John Kluge Chair in Countries and Cultures of the South at the Library of Congress.

In September 2018, the University of Ghana established the Lamin Sanneh Institute, which will promote scholarly research on religion and society in Africa, emphasizing the areas of Sanneh’s expertise, Islam and Christianity.

Many of us know Sanneh’s work as a pioneer in the field of world Christianity. His writings on African Christianity and Islam in Africa are important works for theologians and religious studies scholars alike. Among his many writings and books, two particularly stand out for their impact on the field of study: Translating the Message: The Missionary Impact on Culture and Whose Religion Is Christianity?: The Gospel Beyond the West.

In “Translating the Message,” Sanneh upends the argument that Christianity — as a missionary religion — wipes out the cultures it enters. Rather, Sanneh asserts that Christianity is unique as a missionary religion because it is translated without the language of the founder (Jesus) and invests itself in every language by forsaking the language of Jesus (Aramaic). Christianity is, according to Sanneh, a preserver rather than a destroyer of indigenous languages and cultures. In “Whose Religion Is Christianity,” Sanneh answers questions about Christianity not from a Western perspective, but from the perspective of, as he puts it, “the movement of Christianity in societies that were previously not Christian and societies that had no bureaucratic tradition in which to domesticate the gospel.”

Here lies the crux of Sanneh’s scholarship.

About 15 years ago, several of us were working on a project about the history of world Christianity. At that time, there was an academic debate over what term to use: world Christianities, global Christianity or Christianity in the non-Western/majority world.

None of those fit, Sanneh told Dale Irvin, president of New York Theological Seminary, in an email. Christians outside the West had an equal claim to the word “Christianity.” They are not from a different faith.

“(T)he fight about what name to give to the subject is really a fight of the west and its surrogates to contest the right of Christians elsewhere to consider themselves as equals in the religion,” he wrote. “The countermove with the inclusive title ‘World Christianity’ is intended to force a reckoning with ‘tribal’ view of the west.”

For myself and many other students and scholars, this emphasis on world Christianity opened the doors to scholarship that was not simply focused on Western ideas and theologies. It opened the doors to new ways of thinking about the historical and present-day impact of Christianity in cultures around the world, as well as Islam and other indigenous religions.

I remember when, as a graduate student, I stumbled onto Sanneh’s book “West African Christianity.” Years later, I was delighted to meet Sanneh while I was a junior professor on a project working with world Christianity for Orbis Press. He was cordial, distinguished and welcoming to me, as well as many others.

Sanneh’s loss is deeply felt among his colleagues.

“Africa has lost a great scholar and a public intellectual, whose foundational works on Islam and Christianity vividly capture the religious identities of millions of Africans,” wrote Jacob K. Olupona, professor of African religious traditions at Harvard Divinity School. “Sanneh’s scholarship transverses the two dominant religious traditions on the continent, Islam and Christianity, and has provided significant insight into how they define contemporary politics, identities and civil society.”

Olupona, writing from Nigeria, also expressed his own grief at Sanneh’s passing.

“I have lost a dear friend, a senior colleague and a fellow sojourner in the common quest for African religious space in the global religious community,” he said.

Irvin, who also serves as professor of world Christianity at New York Theological Seminary and as editor of the Journal of World Christianity, called Sanneh “one of the most effective and insightful interpreters of world Christianity in the past century.”

“He was a persistent critic of the entrenched territorial Christendom of the West and the accompanying tendency to reduce Christianity to its Western tribal forms,” Irvin said. “He never tired of asking why should he as an African be considered accountable for the failures of Western colonial Christianity. His brilliance was to see beyond the arrogance of the West to uncover a deeper spiritual truth about the faith he so deeply embodied. We have lost a major prophetic figure.”

Dana Robert, Truman Collins Professor of World Christianity and History of Mission at Boston University, spoke of Sanneh as a “giant in the field of world Christianity.”

“His loss sends a tidal wave across multiple fields, institutions and continents,” Robert said. “He will be sorely missed by those of us who worked with him and called him a friend, as well as by people who knew him only from his powerful writings.”

Greg Sterling, dean of Yale Divinity School, said he recently gave Sanneh’s autobiography, “Summoned From the Margin,” as a gift to the school’s major donors.

“He had no idea that the gift would become the final testament of his life,” wrote Sterling.

In his autobiography, Sanneh wrote: “When someone dies, people say he or she has run out of rains. Life ends when we run dry.”

The rains may have run out for Sanneh, but his memory and scholarship will continue to refresh us for many years to come.

May he rest in peace.