Moving forward always requires rigorous internal criticism of ourselves and the traditions we love. This applies not only to liberal Christians who congratulate themselves for not being like those conservative Christians who support Trump; this applies to people like me who call themselves liberationists and see continued relevance in the tradition of liberation theology that sprang from Latin America. That is why I find it fitting that one of the strongest criticisms of Latin American liberation theology would come from one of its brightest students: Marcella Althaus-Reid, a queer theologian who experienced poverty on the streets of Buenos Aires and who later landed an academic post in Scotland before succumbing to sickness at a relatively young age.

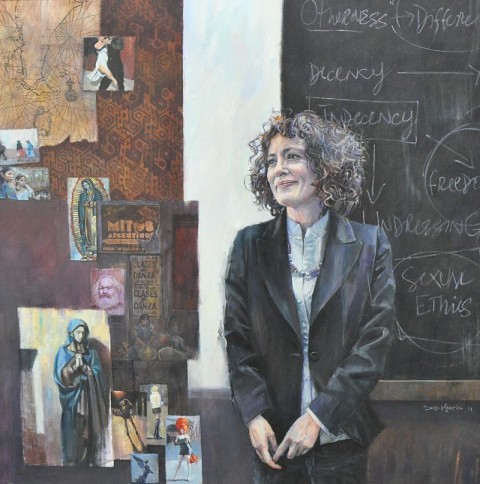

I read Althaus-Reid’s Indecent Theology: Theological Perversions in Sex, Gender and Politics (2000) last year and it blew open my romanticized notions of liberation theology frozen in time, with its early figures like Gustavo Gutierrez and Leonardo Boff, as I had been taught in North American academic settings. In fact, Althaus-Reid helped illuminate the material relations between liberation theology and the ways in which it came to be consumed by or interpreted by “the North Atlantic production line of theology.” All theologies and God-talk operate in economic markets with varying power dynamics. Marcella taught me that.

I was particularly struck by Althaus-Reid’s criticisms of liberation theology on the ground, on its own terms of praxis and solidarity. She recounts with great pain how important liberation theologians did not take sexual oppression seriously:

When some years ago, the Metropolitan Community Church in Argentina sent a letter to a selected group amongst the main liberation theologians in Argentina, Peru and other countries of the Southern Cone, asking them to sign an open letter repudiating the killings of homosexuals in Argentina by a right-wing group, none of them agreed to do so. They were not being asked to sign a letter declaring their support for lesbigay issues, but one declaring that the Bible did not support the killing of homosexuals. However, the theologians of solidarity did not want to show solidarity with victims of sexual persecution, some of them saying that homosexuality was not their issue. The lesbigay Christian community, which was at the time working on the lines of liberation theology, manifested textually that those famous Liberation Theologians had stopped walking in the path (of liberation) years ago. I was impressed by the young man who told me that the liberationists did not walk with the people anymore. And why? Simply because they exercise solidarity on their own lusty grounds only, as their heterosexual drive for power leads them. Solidarity as the expression of a relationship with someone else also reflects a way to relate sexually, in hegemonic dominions, or in a welcoming community of free people and beyond sexual acts. It refers to the understanding of hierarchies and binarism in economics and in theology too.

Many early liberation theologians did not think gender or sexuality was their issue. Yet, Althaus-Reid argues that it was their issue. Christianity and the church introduced a gender system into the Americas and continued to replay colonial notions of virginity and decency. Liberation theology did not challenge decency. Althaus-Reid writes: “Decency is the theory of the proper in Latin America, which is a theological concept inherited from the disruption of the Conquista. The Conquista is, first of all, a theological disruption and hegemonic theological statement.” Liberation theology reinforced the colonial notions of decency and did not challenge patriarchal gender norms. When LGBTQ people were being killed in Argentina, the liberationists had nothing to offer.

To be sure, this tradition which was initially silent on issues of gender and sexuality (and race, and indigeneity) would eventually include or impact voices like Beatriz Melano Couch, María Pilar Aquino, Elsa Tamez, María Clara Bingemer, Ivone Gebara, Ana María Trepedino, Consuelo del Prado, and Ada María Isasi-Díaz. Nevertheless, I think it’s important to remember early liberation theology’s failures.

Ernesto Cardenal said, “Solidarity is the tenderness of peoples.” What happens when we have the rhetoric about liberation and social justice but lack the tenderness? How is our tenderness short-circuited by nationalism, heteronormativity, neoliberalism? What is the meaning of any theology without resistance, without active solidarity with all the marginalized? We are still confronted with these issues.

Subscribe to Practicing Liberation Updates in order to receive periodic alerts about new posts on this blog. This is the best way to stay connected.