Of Gods and Men

Although the French film Of Gods and Men is set in Algeria in 1996, it could just as easily be set in any Middle Eastern or African country that is struggling with the rise of Islamic extremism. You can see the film playing out in any number of dangerous locales over the centuries—anywhere where people of Christian, Muslim or another faith have to make difficult choices that involve their beliefs in a higher power.

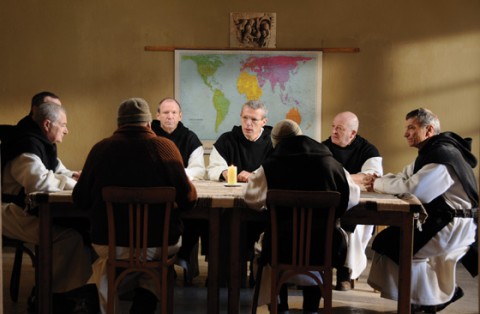

This thematic universality is the strength of a well-crafted and beautifully photographed film, one that's light on action but heavy on ideas. The story involves eight Cistercian Trappist monks who are living a pious life of service in an old abbey in the Algerian countryside. Their peaceful days revolve around praying, chanting, reading, farming, raising bees and serving the small community of Muslims who live down the hill in the village. The monks provide practical help (medicine, clothing, food) as well as emotional support, evidenced in a lovely scene in which aging Brother Luc (the great French actor Michael Lonsdale) gives advice on the vagaries of love to a quiet Muslim girl.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

But the monks' bucolic existence is threatened when an Islamic revolution challenges the corrupt government, and acts of brutality become commonplace in the region, from the ritualized execution of an immodest young woman to the murder of a team of foreign workers. It doesn't take long for those in power to sense that the Christian monks might be next and to warn the monks that it's time for them to pack their robes and serve elsewhere.

But like the warriors in The Seven Samurai, the monks refuse to run, choosing instead to stay and support the village and the villagers they love. The discussions among the monks as they debate the merits of leaving versus staying are riveting; we learn bits and pieces about their personal lives and the reasons they became monks in the first place.

Leading the discussion is Brother Christian (Lambert Wilson), the learned head monk who has become an expert on the Qur'an and who, like the old philosopher in Eugene O'Neill's The Iceman Cometh, is cursed to always see both sides of every question. While he fears for his life and the lives of his brothers, he seems to understand the reasons behind the extremists' anger. He believes that if the monks stay, they may be able to make a difference.

This dilemma is well illustrated in one tense scene. On Christmas Eve, extremists break into the abbey looking for medicine for a wounded comrade. Brother Christian not only convinces them that the monks need all their medicine for the children of the village but also uses his knowledge of the Qur'an, with its reverence for Jesus, to chide them for interrupting a worship service. Though the scene ends with a handshake of mutual respect, we sense that things are only going to get worse.

From this point on, the film walks a fine line as it shows off one of its greatest strengths while confronting its main weakness. On the plus side, Caroline Champetier's cinematography is magnificent. Her static shots of the monks conjure up Renaissance paintings, complete with soft light falling through windows and across the monks' faces. On the minus side, the film seems to end both cinematically and spiritually at the 100-minute mark, then drags on for another 20 minutes. When the ending arrives, the viewer may feel less a sense of catharsis and more a sense of relief.

In spite of this, Of Gods and Men is thought-provoking; it forces us to debate questions of vocation and commitment as seen through the prism of our religious convictions. Though it never reaches the holy heights of celebrated "crisis of faith" movies like Ingmar Bergman's Winter Light or Robert Bresson's Diary of a Country Priest, Of Gods and Men is gazing up at the same peak.