Wild Grass

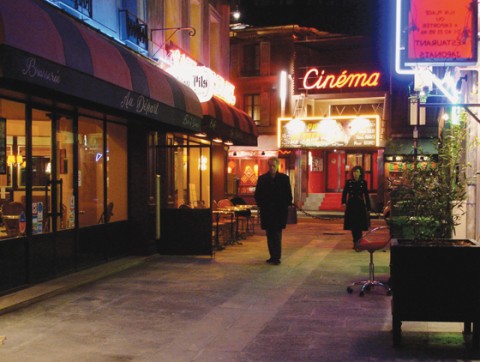

What is most startling about the iconic French director Alain Resnais is not that he is still making movies at the age of 88, but that his films still demonstrate such an unbridled love of cinema and its power.

Though best known for his groundbreaking movies of the 1950s and 1960s, Resnais has never stopped directing. Artistic naysayers have criticized his later work for lacking the philosophical import and intellectual gravity of his early classics, but this misses the point. Resnais is all about emotion—happy, sad and everything in between—and whatever it takes to squeeze that emotion out of his audience he is willing and eager to do. This includes his joyous use of artifice, light and shadow, contrasting color schemes and jumpy editing, along with his manipulation of familiar cinematic conventions, from voiceover narration to flashback and superimposition.

All of these techniques are on display in Wild Grass, a primer for how style and content can work together to create emotion. Based on the 1996 novel The Incident, by Christian Gailly (the first book adaptation Resnais has done), the tale's setup is deceptively simple. A single, red-haired, middle-aged dentist named Marguerite Muir (played by Resnais's wife and muse, Sabine Azéma) has her purse stolen after shopping for shoes. (You know you're in Resnais territory right off the bat when the narrator spends time before the robbery debating the pros and cons of purchasing new shoes.) Later, the purse's wallet is discovered in a parking garage by 60-something husband and father Georges Palet (André Dussollier, another Resnais regular).

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Georges is something of an enigma—either he has a shady past or he likes to believe he has, which is why the simple act of returning a wallet proves to be taxing. First, Marguerite's ID photo reminds him of a famous aviator from the 1930s, which is curious since Marguerite owns a small plane. Also, his sense of adventure is piqued, and he can't help imagining what twists and turns his life may take when he returns the wallet—which is why he is so angry when Marguerite, over the phone, simply thanks him for his kind act. He brazenly proclaims his disappointment at her feeble thank you, she is shocked at his crust, and the process of trying to find a balance between civil politeness and thwarted passion becomes the engine that drives the story.

Along the way, Resnais introduces us—with the help of a witty and often smug narrator—to the other players in this warped love story, including Georges's younger and more patient wife, Suzanne (Anne Consigny), Marguerite's friend and co-worker Josépha (Emmanuelle Devos) and a pair of police officers (Mathieu Amalric and Michel Vuillermoz) right out of a Monty Python skit. Together, they wring more emotion out of a lost-and-found story than most directors can squeeze out of a series of deathbed scenes.

Resnais has said that part of the reason he finally agreed to do an adaptation of a novel is that he loved the "musicality" of Gailly's language. This language keeps the movie alert and helps with characters who are a bit over the top when it comes to speaking and reacting. This features brings to mind Jacques Demy's 1964 film The Umbrellas of Cherbourg, in which the characters sing their dialogue instead of speaking it. Despite the dramatic musical score by Mark Snow, there is no actual singing in Wild Grass, but the setups and emotions are so pronounced that it wouldn't seem out of place if a character were to throw open his or her arms and burst into song about the vagaries of life and its disappointments.

The other key difference between Cherbourg and Wild Grass is that while the former deals with young love, the latter is focused on last chances. The more serious subtext to the film—easily lost amid the gaiety of the filmmaking—is that Marguerite and Georges are not content with their lives. Though they are urged to move on—he to his family, she to her patients—the randomness of the encounter has opened up possibilities that they never knew existed. Should they go home and tend to their own gardens? Or should they allow their emotions, like wild grass, to grow wherever they please?