Kingdom-sized desire

I fell desperately in love at the age of 17. I'd run to the window overlooking the street, hoping "he" would arrive unexpectedly. Even when I knew he was far away at college, I flew like a trapped bird toward that window in a kind of irrational frenzy, not knowing what to do with the energies of my desire to see him. Long after he found another girl, and I, chastened, settled into an unhappy first marriage, I noticed that the longing I once associated with love formed the landscapes of my soul. Longing formed a permanent crater from which all paths led. Atmosphere, scenery, the byways, scents, moods, silences—all unfolded from the moment of conscious longing. Longing opened my soul to infinite exploration, providing the passport, the vehicle, horizons and destination. Even the nourishment offered along the way tasted like longing.

As the mystic John of Ruysbroeck said, "The inward stirring and touching of God makes us hungry and yearning; for the Spirit of God hunts our spirit; and the more it touches it, the greater our hunger and our craving. And this is the life of love in its highest working, above reason and above understanding; for reason can here neither give nor take away from love, for our love is touched by the Divine Love." I suppose my lover did me a big favor. Fortunately, through the series of coincidences that often takes place around the time of religious conversion, I found a literature of longing—biblical, spiritual and mystical.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

I found relief praying the Psalms: "My soul thirsts for you, my flesh faints for you, as in a barren and dry land where there is no water" (Ps. 63:1). "As the deer longs for the water-brooks, so longs my soul for you, O God" (Ps. 42:1). In addition to Christian mystics, I found that mystical literature of every religion uses erotic imagery without shame or apology. We're all longing for love. Wherever we look we find the language of longing at the heart of the quest for God. Are we made for love? This perpetual longing, the unquenchable thirst for intimacy, the gargantuan appetite for love, seems to me the most natural state of being.

Fortunate are the ones who realize early enough that another human being can't possibly respond to this unrequitable need for love! (Fortunate, too, the would-be lovers who can't fulfill our desires.) Even more fortunate are men and women of prayer who realize that peace comes by embracing the longing itself. Addictions and loneliness can mask this deeper longing for God. Our material culture exploits these natural longings. Screaming advertisements dupe us into believing that a product, a gadget or some glittering things will satisfy our unformulated, nonspecific desires. It all comes at us so fast! We can't allow ourselves to reflect, to feel foolish about it before we buy more stuff like an addict no longer in touch with his conscience.

In his book The End of Overeating, David Kessler shows that food engineers concoct the perfect combinations of salt, sugar and fat to trigger a chemical craving in the brain so that we will addictively buy a food product or revisit a particular restaurant. Manufacturers of foods manipulate our brain chemistry just as big tobacco companies did with additives to cigarettes. The poor are particularly vulnerable to addictive, nonnutritious foods and "food-like substances." In urban areas sometimes the only access to anything like a grocery store is a small bodega full of unhealthy snacks and sodas.

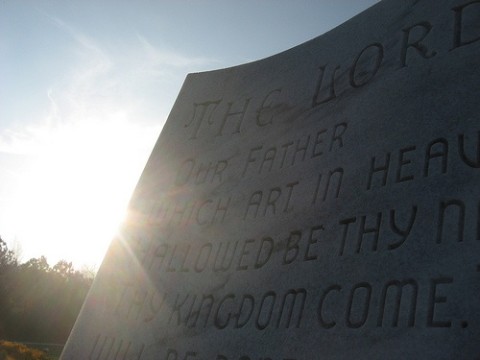

The prayer that Jesus taught acknowledges the longing embedded within us. Thy kingdom come! We beg the kingdom come to satisfy our kingdom-sized desire. We beg for union of heaven and earth, for bread, for healing of our sins and for relief from suffering and evil. Jesus acknowledges our needs, our inborn desires—the sense of unrequited love, the knowing that our love can't be fulfilled temporally. To sit with the Lord's Prayer is to sit with longing.

As many people throughout the centuries have confessed, this prayer brings peace and completion. The benediction sweeps us up along with it toward the sphere of God: for thine is the kingdom, the power, the glory. . . . I in Thee and Thee in me. So it is good to have learned along the way that my very capacities for intimacy, the landscapes of my longing, equip me for a life of prayer. For what is prayer, really? Prayer is longing for that which cannot be satisfied. We are created for love, a love unbounded by time and space. Within a culture of approved addictions and frantic quests for the satisfaction of appetites, longing becomes prayer itself: a charism of paradoxical calm.

Perhaps the longing in us is God's primal longing, just as our very corporeality on the quantum level consists of primal star matter. Perhaps it is as Job hoped: "You would call, and I would answer you; you would long for the work of your hands" (14:15).