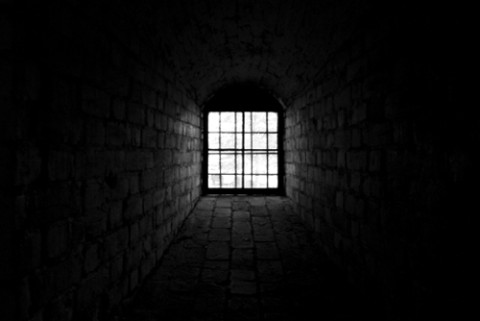

Put away: Solitary confinement

Prisoners at California's Pelican Bay State Prison caught the nation's attention in July with their three-week hunger strike. Their protest originated in the half of the prison that's called the Security Housing Unit, where some 6,600 inmates spend 23 out of 24 hours a day for years on end in small, windowless cells. In its editorial "Cruel Isolation" (August 2), the New York Times spoke out against Pelican Bay and the excessive use of solitary confinement in U.S. state and federal prisons.

While the U.S. persists in using confinement as punishment, the Geneva Convention forbids excessive use of the practice. Even at Abu Ghraib in Iraq, where acts of sexual humiliation and physical abuse were officially approved, a decision to keep a prisoner in isolation for over 30 days required special permission from the commanding general. This is because, as University of California psychologist Craig Haney observed, many prisoners in solitary confinement "begin to lose the ability to initiate behavior of any kind, sinking into chronic apathy, lethargy, depression and despair . . . sometimes even to the point of becoming catatonic."

In the New Yorker article "Hellhole" (March 30, 2009), Atul Gawande reported on a study of 150 naval aviators who had been imprisoned in Vietnam. The men told of having found "social isolation to be as torturous and agonizing as any physical abuse they suffered." Senator John McCain has concurred. "It's an awful thing, solitary! It crushes your spirit."