Hebrew Bible purchased for $38.1 million on display at Jewish museum

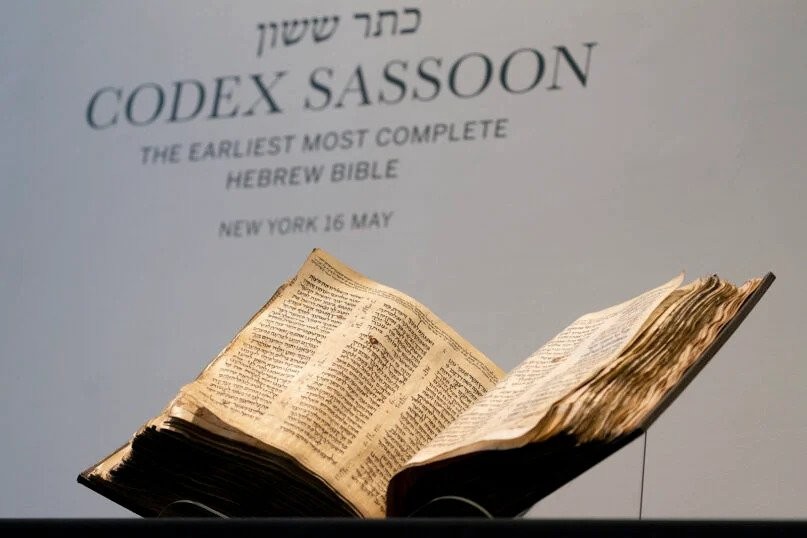

Sotheby's unveils the Codex Sassoon for auction on February 15 in New York. (AP Photo/John Minchillo)

The Codex Sassoon, a late ninth- or early 10th-century book Sotheby’s has dubbed the “earliest, most complete copy of the Hebrew Bible,” was sold for $38.1 million Wednesday afternoon to American Friends of the ANU, Museum of the Jewish People. It will become part of the museum’s core exhibition and permanent collection in Tel Aviv, Israel, according to Sotheby’s.

The purchase of the Codex Sassoon was made possible through a donation of Alfred H. Moses, a former US ambassador to Romania, and his family. It’s one of the most expensive historical documents ever sold at auction, clocking in just below the $43.2 million US Constitution sold in November 2021 to art collector Ken Griffin.

“The Hebrew Bible is the most influential book in history and constitutes the bedrock of Western civilization. I rejoice in knowing that it belongs to the Jewish People. It was my mission, realizing the historic significance of Codex Sassoon, to see that it resides in a place with global access to all people,” Moses said in a press release. “In my heart and mind that place was the land of Israel, the cradle of Judaism, where the Hebrew Bible was originated.”

The codex doesn’t derive its value from the hundreds of sheepskins required for the parchment of the 26-pound book, the labor required to hand-write the 24 books of the Hebrew Bible, or even necessarily the precision of the text itself—the Aleppo Codex, a Hebrew Bible manuscript created around 930, is known for its unparalleled quality.

Instead, as Tzvi Novick, who holds the Abrams Chair of Jewish Thought and Culture at the University of Notre Dame, Indiana, said in an interview, “The claim to fame of the Codex Sassoon lies in its combination of earliness and comprehensiveness.” And, Aaron Koller, professor of Near Eastern and biblical studies at Yeshiva University, added, there was simply nothing else like it on the market, with other codices from that era already secured by museum collections.

“The carbon dating was really important for them because they had initially thought to offer it for a bit less until the carbon dating came back, plausibly around 900CE, which would make it as early as or even a little earlier than the Aleppo Codex,” said Koller.

Though specifics about Codex Sassoon’s origins are murky, experts date the biblical copy to roughly 1,100 years ago in Syria or Israel. In the 13th century, the codex was dedicated to a synagogue in present-day Syria that was later destroyed. It then vanished for roughly 600 years before resurfacing in 1929, when it was purchased for 350 pounds by British collector and Hebrew manuscript enthusiast David Solomon Sassoon.

Eventually, Swiss financier Jacqui Safra purchased it for $4.2 million in 1989.

For centuries, the codex has been largely obscured from public view. But a global tour earlier this year brought the book to London, Tel Aviv, Dallas, Los Angeles, and New York City. Currently researching at Cambridge, Koller was invited to view the codex outside of its display case while it was being exhibited at Sotheby’s in London.

“We have names and places of this sort of trail of cultural patrimony as it’s going around different communities, moving from country to country. It’s gone on quite a journey,” said Koller. “So to get to your hands, I find that very moving in terms of the artifact itself.”

The codex is inscribed with ownership records as well as commentary for preserving the proper recitation and inscription of the text.

“It’s not written for liturgical performance, it’s written for study, and it also could have been written as a model for scribes when scribes were writing scrolls of the Torah,” said Novick. “It’s one of these texts that preserved the Masorah, literally ‘the tradition.’“

In the codex, Novick explained, the Masorah takes the form of notes in the margins and an annotation system that indicates the correct pronunciation and vocalization of the text.

“Hebrew was written only consonantally, so the project of preserving the vocalization of the text is a real challenge,” Novick noted.

According to Koller, the text of Codex Sassoon would have emerged in an Islamic cultural context. He said that because Arabic, like Hebrew, is written with consonants, Muslims “invented a system of dots to mark vowels and to transmit to a reader everything you need to know to read accurately.”

It was only around the ninth century, Koller said, that Jewish communities began writing whole Bibles using a similar system. He added that exposure to the artistic and sacred Arabic script used throughout the Muslim world may have also informed the scribe who authored Codex Sassoon.

“The aesthetic sensibility is, first of all it’s new, and I think it’s also the effect of Islam in the world of biblical manuscripts,” said Koller, who pointed to the beautiful writing, the high quality parchment and the way many of the pages are framed by notes in the margins. “This is a new way of thinking about a text as something that’s not just pragmatic, but can actually be artistic.”

In interviews before the auction, both Koller and Novick expressed hopes that the codex would be able to be viewed by the public after it was sold. According to Irina Nevzlin, chair of ANU’s board of directors, that wish is being granted.

“We will be eternally grateful to Ambassador Moses and his family for ensuring that the most treasured, historic and complete Bible in existence will be permanently displayed at the world’s largest Jewish Museum,” she said in a statement. —Religion News Service