The wisdom of dreamwork

“I don’t interpret dreams,” says poet and spiritual director Rodger Kamenetz. “I bring them to life.”

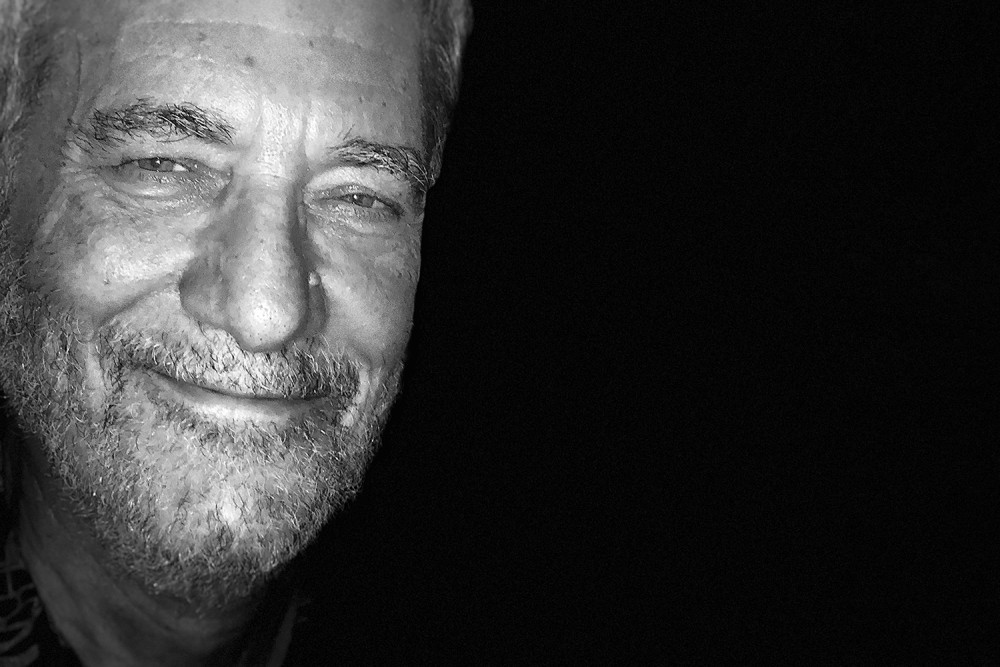

Poet and spiritual director Rodger Kamenetz (Photo by Moira Crone)

Rodger Kamenetz is an award-winning poet, teacher, and dreamworker. His books include The Jew in the Lotus, Terra Infirma, The History of Last Night’s Dream, and Burnt Books. He pioneered the creative writing department at Louisiana State University and now lives in New Orleans, doing spiritual direction and dreamwork. A version of this interview originally appeared in season 2 of the century podcast In Search Of.

Tell us how you became interested in dreamwork.

As a kid, I had repeated, scary falling dreams. When I was in college, I thought to start writing down my dreams because they might be fodder for poetry. I had a very utilitarian attitude: “What is the use of something?” That’s an infection of our culture. Everything is about its use.