There’s no such thing as a Bonhoeffer moment

Dietrich Bonhoeffer didn’t choose to be a martyr. He simply tried, as many others did, to be decent in the face of evil.

In almost every lecture I have ever given on Dietrich Bonhoeffer, someone has asked this question: Are we in a Bonhoeffer moment?

It is usually a question about some current issue of moral urgency, a “here I stand” moment that demands that we speak out as Christians: an election. Racial justice. Israel/Palestine. Abortion. The future of Christian faith. The challenges of American culture. LGBTQ issues. Denominational tensions. Over the years the question has been posed by progressive Christians, evangelicals, “nones,” and everyone in between.

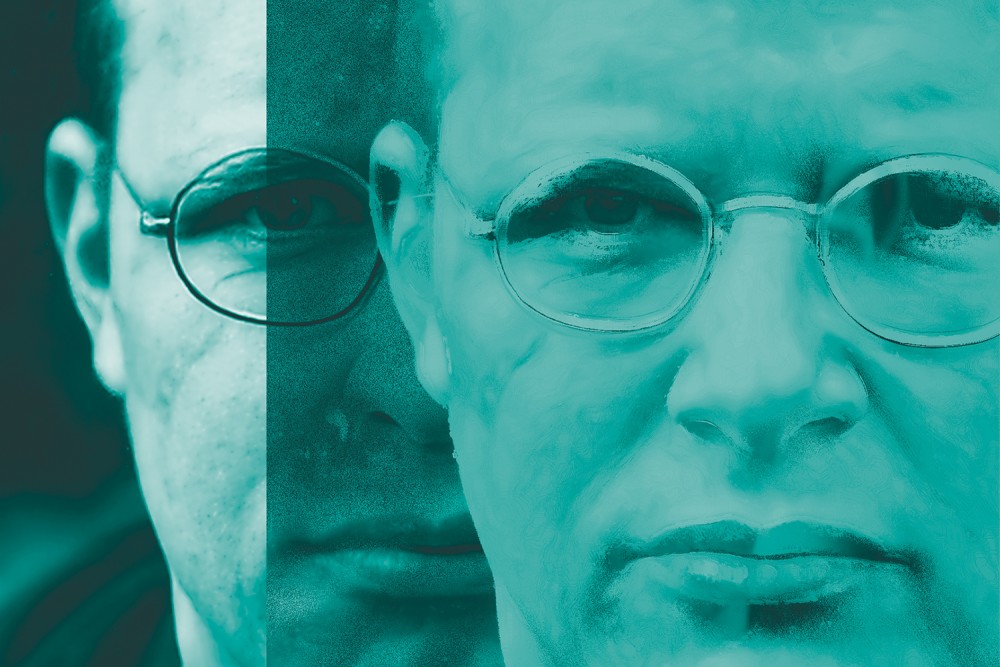

I have my own strong views about all these things, but there’s a bigger problem here. The very notion of a “Bonhoeffer moment” is based upon the widespread, overly simplistic image of Dietrich Bonhoeffer as a Christian activist and hero, moved by conscience and faithfulness to his Lord, who singlehandedly led his church in its fight against Hitler and was ultimately executed for rescuing Jews and trying to overthrow the Nazi regime. Most American versions of Bonhoeffer (particularly in popular books and films) draw on that heroic image, tweaked over the years to conform to certain sensibilities: Bonhoeffer as feminist, as countercultural evangelical, as progressive Christian, as Christian nationalist.