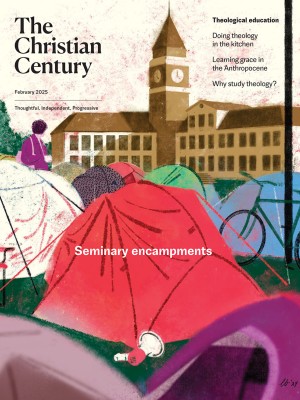

From seminary classroom to encampment

Students protesting the war in Gaza are asking deep questions about colonialism, antisemitism, and Christian Zionism.

Illustration by Leonie Bos

Last April, when students at Emory University began their encampment to protest the war in Gaza and demand divestment, I showed up as a faith leader to support and witness students at Candler School of Theology and Emory’s Graduate Division of Religion protesting alongside them. This multiracial, mostly Christian group of students had occupied a Candler academic building, transforming its lobby into a zone of support and solidarity.

I was struck by the contrast between the clarity and forthrightness of their activism and the response of the broader church. I knew similar things were happening at other seminaries and divinity schools. What did it mean for students to belong to these institutions—historically and presently associated with the Protestant mainline, housing various sorts of progressive Christianity—and also to respond decisively to what was happening in Gaza?

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

There are significant variations in student organizing for Palestine at seminaries and divinity schools, from the number of students involved to the strategies they engage. At Union Theological Seminary more than 50 students have been involved in organizing for Palestine. Dozens have engaged at Yale Divinity School, and smaller numbers at Duke Divinity School, Garrett-Evangelical Theological Seminary, and Princeton Theological Seminary. Broadly speaking, the students are young, racially diverse, and mostly (but not entirely) Christian. Many of them were present at encampments on affiliated or nearby university campuses last spring.

This fall, I interviewed ten mostly Christian-identified students at these five schools about their activism and experiences in university encampments. We discussed how their advocacy for Palestine connects to other commitments, including combating antisemitism, what they want from their institutions, and what all of it has to do with their faith.

On the first day of Princeton University’s encampment, students from Princeton Theological Seminary made hundreds of burritos in one of their dorms across the road to feed students in the encampment. They worked with local community members and pastors to provide supplies and blankets. They did laundry for students. One seminary student was there every day helping coordinate food distribution and nightly cleanup.

Yale Divinity students spent time in the Yale encampment as witnesses, providing care for students being released from detainment, and remaining, as one student explained to me, “in constant prayer.” Many students organically assumed the role of chaplains in the encampment, where news and footage of continued bombings produced a steady stream of grief. “We were putting our education to use,” said Angel Nalubega, a Black Episcopalian fourth-year seminary student at Princeton. “We were using the pastoral skills that we have been trained with and applying them to serve our community, and through that trying to uplift and care for the Palestinian community more broadly.”

Students pointed out that care provision within the encampments was mutual. Nalubega recalled having some of the “cruelest, most horrific things” she’s ever heard screamed at her by counterprotesters at Princeton’s encampment. At one point, a Jewish student stepped in to protect her from someone shouting epithets—a personal example of the broader spirit of solidarity she said permeated the space.

Various students described people making art together and ensuring everyone had what they needed, including medical care, social worker support, spiritual support, and food—so much food. Students described an abundance in the midst of shared grief and vulnerability.

Yarilynne Esther Regalado spent time in the Columbia University encampment last year as a third-year MDiv student at Union. She identifies as Christian and is the child of immigrant parents from the Caribbean. “I haven’t been the same person after having been a part of such rich, communal sharing and learning,” she said. “Seeing all that was happening—the art section, food, medicine, blankets . . . it was all defined by such profound care.”

Logan Crews, a second-year MDiv student at Berkeley Divinity School at Yale and a White Episcopalian, is one of the student leaders of Yale Divinity Students for Palestine and was arrested for protesting last year. She felt “like the Holy Spirit was moving and shaking things up,” she said about her time in the Yale encampment:

“It felt like an event outside of time and space. It was a beautiful act of imagination. Those of us who showed up to the encampment felt called there the same way we were called to YDS. A lot of us were wondering if this was why we were called to the seminary, especially those of us who were first-year students . . . whether it was for this very historic moment.”

Peter Tanaka is a fourth-year student at Union and cochair of its student senate. He identifies as half Japanese and half White and as both Christian and Buddhist. Reflecting on his experience in the Columbia encampment, he shared the following:

“One of the moments that stands out for me the most was the first encampment when police did come in. Hundreds of students were surrounding the lawn and marching around it. We sat in two circles: we had people on the outside and people on the inside, and our arms were linked. We were singing songs, and some of them were scripture, like the Song of Ruth—Where you go, I will go, my friend, your people are my people and my people are your people, and our struggles align. I was seeing these undergraduate and graduate students—many who are now suspended or expelled—singing this song and starting to cry as people started to get taken. It was such a powerful moment. It felt like a collective prayer for liberation.”

Tanaka was arrested that day, and again on April 30 when the NYPD raided Hamilton Hall, which Union students had occupied and renamed “Hind’s Hall” in honor of Hind Rajab, a six-year-old Palestinian girl killed by the Israeli military in Gaza in January. Hind’s family was fleeing Gaza City by car when the Israeli military fired on them, killing everyone inside but the girl. When two paramedics arrived to rescue Hind, military forces proceeded to kill them as well. Their bodies were recovered at the site two weeks later along with those of Hind and her family.

At Yale, a group of Berkeley students brought morning prayer services to the encampment, and other student groups followed suit. At Princeton, a procession of about 25 seminary students walked several blocks from the seminary to the encampment, accompanied by a few faculty, and later held a communion service. At Northwestern University, Garrett seminary students led a service of song and prayer. Union students held two open table communion services at different iterations of Columbia’s encampment. At the first one in April, service leaders distributing communion walked to the gates of campus, flanked by lines of police, to offer bread and wine through bars to community members there to show support. Students explained that this was a deliberate liturgical reference to the militarized checkpoints that restrict Palestinian movement in the West Bank and Gaza.

Multiple services led by students referred to statements or ideas from Palestinian Christian theologians Munther Isaac and Mitri Raheb, and one quoted a prayer by Palestinian American Episcopal priest Leyla King. In their own formation and activism, students named an intention to center the voices of Palestinians and especially Palestinian Christians, who have called on Western churches to repent of their participation in their oppression.

Like many of my clergy peers, the student organizers with whom I spoke were concerned about antisemitism and its relationship to their pro-Palestinian organizing. They spoke of collaborating with anti-Zionist Jewish university students, modeling an ecumenism that is spontaneous, organic, and founded on shared values. They report learning from these colleagues how to engage the struggle for Palestinian liberation in a way that is sensitive and responsive to the realities of antisemitism, one that presupposes and insists upon a distinction—which others contest—between the religion of Judaism and the political ideology of Zionism. Several of them made a point of noting fellow organizers’ swiftness to address antisemitism among students when it did emerge.

Hima Bindu Thota, a second-year Indian American Christian student at Duke, explained that she’s learning from anti-Zionist Jewish organizers how to carefully disentangle an ancient, venerable religious tradition from nationalism. Through her time with anti-Zionist Jewish colleagues on campus, she has learned to challenge Christians to extricate their own tradition from its colonial and nationalist impulses, past and present.

Another Duke student, Joe Meinholz, a White candidate for ordination in the United Methodist Church, said this:

“The question that’s been posed to me by the local rabbi that I really want to stick with is, ‘Why are you speaking up and from where are you speaking when speaking against the modern nation-state of Israel?’ Speaking against the modern state of Israel is something we need to do when they enact genocidal policies, but it’s not in any way because it’s the Jewish state, and given the Christian legacy of antisemitism, we have to combat these tropes when they arise.”

Meinholz added, “In the end, who shares responsibility to make sure Jews are safe as our neighbors? All of us, but especially Christians as a part of institutions that have historically excluded them.”

This is a tense line to walk, particularly for White Christians whose tradition bears responsibility for the need for Jewish safety and the spread of colonial practices and ideologies. Tanaka names this tension, referring to his school, Union:

“As a historically White, Anglo-Saxon Protestant institution with a history of antisemitism, how do we address this? We have to be aware of our history, but I don’t think that means we don’t speak or that we shy away from these conversations, because there is a genocide happening right now. We need to be aware of the complicated histories we have, and still, we should speak.”

While student activism for Palestine has been characterized as hospitable to antisemitism, the students I talked to criticized their institutions for not addressing antisemitism more thoroughly. In an October 2023 statement from Princeton’s organizers, signed by 70 students, the first demand was “an audit, at a minimum an inquiry, into the history and development of dispensationalist and millennial theologies at the seminary.”

A Yale student who wished to remain anonymous agrees with some of the arguments made by former student Esther Levy in an April op-ed for the Yale Daily News titled “Yale Divinity School Has an Antisemitism Problem,” namely, that the school provides a superficial treatment of antisemitism and supersessionism in its courses and little education on Jewish history or the vast and varied richness of Jewish tradition. The student said that, unfortunately, antisemitism is too often treated cursorily “as something that has already been fixed instead of something that’s alive and growing.”

Fellow Yale student Crews observed, “I think the movement for Palestine on a lot of campuses has been a scapegoat—look at how we’re dealing with antisemitism because we’re dealing with this movement—instead of looking inward at what’s been there rotting underneath the surface of our academics and our community life.” All the students I spoke with agreed that this work must include a critique of the anti-Jewish theology embedded in Christian Zionism—a conversation they said their schools have been reluctant to have. In their view, the conservative version of Christian Zionism—in which Jews’ return to Israel (and en masse conversion to Christianity) is a celebrated chapter in the Christian drama of salvation—is manifestly anti-Jewish and should be challenged directly.

Abby Holcombe, a White UMC pastor who graduated from Garrett last year, said this of her school: “We should be calling out antisemitism and Christian Zionism in the same way we talk about racism and homophobia. We won’t talk about Zionism at all because we’re scared to say anything antisemitic, or anything deemed antisemitic. Unfortunately, we’ve forsaken the whole conversation.”

Most of the students I spoke with described learning about Palestine for the first time in the context of other movements for justice. For Meinholz, it was working with Indigenous people in the Great Lakes region and, through that work, learning more about his position “as a descendant of settlers in this land.” After October 7, he heard Indigenous leaders speaking out against Israeli aggression in Gaza and—without drawing one-to-one comparisons, he was careful to note—he began to draw connections between Palestinian and Indigenous struggles within the framework of settler colonialism. “That drew me in,” he explained. “I don’t want the settler way of being, in which some people secure land by dispossessing others, to keep spreading.”

Meinholz, Nalubega, and Tanaka all learned about Palestine for the first time through their involvement in the Black Lives Matter movement. For Nalubega it was during the Ferguson uprising, which coincided with the six-week Gaza war in the summer of 2014. Many have written about the bonds of solidarity between BLM and Palestinian activists, who used social media to teach Ferguson protesters how to treat tear-gassed eyes. Crews, who’s from St. Louis, connected with BLM organizing there in 2020 and first learned about the Palestinian struggle from that community. The same year, Tanaka was in Detroit and began going to BLM marches. He described a strong coalition between Black and Palestinian organizers in the city and remembers marching for Palestine with BLM organizers in nearby Dearborn, Michigan. Those were his first experiences of community organizing and activism, and the lesson that no one issue stands on its own was deeply formative.

In 2014, Thota visited Palestine, and the systemic discrimination she witnessed there was a gateway to deeper understanding of racism and anti-Blackness at home. While there, she saw images of Palestinians holding up “Free Ferguson” signs. “Palestinians have been linking these movements for a long time—we are following them,” she said.

Connections made in the streets are deepened in the classroom, where students study civil rights icons like Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X, and Abraham Heschel and freedom fighters like Óscar Romero, Nelson Mandela, and Rigoberta Menchú. They described everyday classroom conversations about empire, colonialism, racism, justice, and what it means to be human. And they read liberation theologies: Latin American, Black, womanist, queer. Several students mentioned James Cone’s work as especially influential. As Crews put it, Cone taught her “to see Jesus in oppressed peoples who are facing state violence.”

Nalubega argued that “to refuse to care about people in the very land in which our Savior was born and died, to refuse to participate in any real liberation movement, is a betrayal of my Christian values. My education is directly tied to community. I see all people as part of that community, especially marginalized people.”

Many students named the problem of living with a perplexing and painful dissonance between their studies, which encourage them to take their faith seriously and to reflect theologically on injustice and oppression, and their schools’ unwillingness to name and denounce what the students believe is an ongoing genocide. Pragmatically, students are calling on their institutions to divest from weapons manufacturing, to call for a permanent ceasefire, to condemn the war in Gaza as genocide, to condemn Israeli policies as apartheid, and to provide better education on multiple facets of this crisis. Everyone I spoke to felt disappointed by how their schools have responded. Yet they continue to push, believing in their schools’ power and responsibility to contribute to positive social change—particularly those that claim their schools’ legacies as part of their own identities.

In pressuring their institutions in this way, students locate themselves in a long tradition of activism, some instances of which their schools now memorialize and celebrate. In his 2017 book We Demand: The University and Student Protests, Yale University professor Roderick Ferguson suggests that “we begin to see student protests not simply as disruptions to the normal order of things or as inconveniences to everyday life at universities.” He goes on,

Student protests are intellectual and political movements in their own right, expanding our definitions of what issues are socially and politically relevant, broadening our appreciation of those questions and ideas that should capture our intellectual interests: issues concerning state violence, environmental devastation, racism, transphobia, rape, and settler colonialism.

Might we consider seminary and divinity school activism for Palestine a theological movement in its own right, posing a challenge to institutions of theological education—and to progressive Christian institutions more broadly? What would it mean to grapple more thoroughly, as these students invite us to do, with colonialism, Christian Zionism, and perhaps nationalism, all as part of our institutions’ commitments to social justice?

Law professor Mari Matsuda, one of the founders of critical race theory, once poetically characterized it as “the refusal, ever, to ignore harm to human bodies.” Nalubega explained that, fundamentally, she and fellow students “were activated by the mass death we were seeing on our phones every day.” Students open social media apps to behold children blown up and shot, people buried or burned alive, babies dying of starvation. Their activism is a refusal to accept that this kind of harm is necessary or permissible in our world and a refusal to let the institutions they are a part of accept it either.

Feeling disappointed and marginalized, many of these students are questioning their investments in church institutions like my own. Whatever their future vocations, they have planted seeds of a Christian commitment to Palestinian liberation, one that is interwoven with a responsibility to counter antisemitism and dismantle White supremacy. They’ve demonstrated new configurations of interfaith solidarity and a readiness to upset the status quo. They are asking what God’s dream of life and liberation for all people means now and moving to realize it, working through questions and across difference as they go.