Sanctuary in houses of worship has always been tenuous

It’s a practice marked by promise and difficulty—both in the Bible and today.

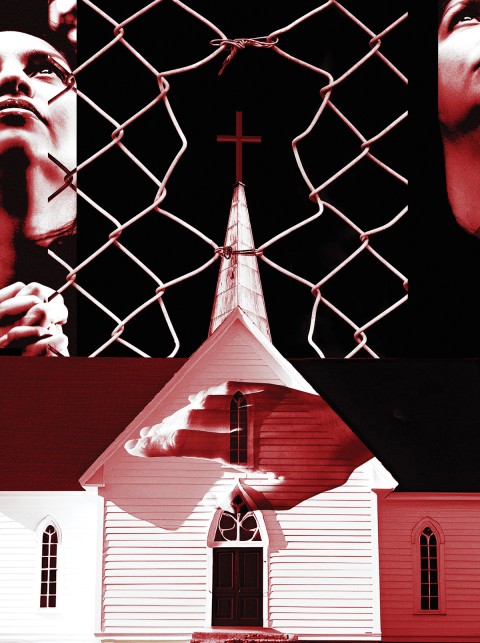

Century illustration (Source images: Getty)

On Inauguration Day, the Trump administration altered existing Immigration and Customs Enforcement policy to allow arrests to be made in “sensitive locations” such as houses of worship. Since that change, much attention has been given to an ancient practice with modern impact: sanctuary.

Two distinct practices of sanctuary took root in American religious life in the last few decades, each as a form of protest. The first was in the 1980s, when the Reagan administration denied asylum claims for people from countries ruled by US-backed regimes. The second, which I’m part of, emerged about a decade ago in protest of US immigration policy. They were unequivocally successful, changing the legal landscape with ABC v Thornburgh and establishing a legacy of sanctuary cities and campuses that continues today.

Both the sanctuary movement of the 1980s and the new sanctuary movement of the 2010s housed people in houses of worship and gave them a platform to speak about their situation—a strategy they derived from the Hebrew Bible. Mosaic law prescribes sanctuary cities for those guilty of accidental manslaughter as a sort of forbearance of revenge. But the biblical tradition most directly connected to present-day practice is altar sanctuary. Looking at this tradition in the Hebrew Bible can tell us something about the strengths and weaknesses of sanctuary today.