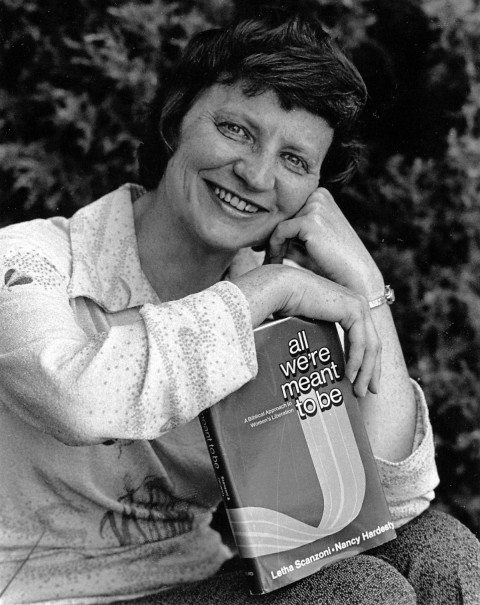

My evangelical feminist friend Letha

There is no greater evidence of how much Letha Dawson Scanzoni valued relationships than her letters.

When I first walked into Letha Dawson Scanzoni’s apartment—which was, principally, a working office—I was astounded by how many books she’d packed into the floor-to-ceiling bookcases that lined all four walls of her small living room. I had traveled from Texas to her home in Norfolk, Virginia, to become better acquainted with the influential evangelical writer. While letting me peruse some of her files one summer afternoon, she also seemed to be interested in getting to know me, something I found unfathomable.

Over time I found out how much being in the company of these books meant to her. But she had another treasure. “I love letters!” she said to me, surrounded by papers scattered across her floor. In the closet were several large binders, bulging with letters she had received and copies of her replies, including correspondence with her co-authors Nancy Hardesty (All We’re Meant to Be) and Virginia Ramey Mollenkott (Is the Homosexual my Neighbor?). More letters were hidden away in her numerous filing cabinets, volumes upon volumes of correspondence with readers, unknown to most everyone. They speak to the intimacy she valued with her readers. Perhaps there is no greater evidence of how much she valued relationships than her letters.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Scanzoni, who died early this year at age 88, was born in 1935 in Pittsburgh. When she was a young girl, her parents encouraged her to dream big: “There isn’t anything you can’t do,” they told her. She took them at their word. At 12, she chose to play the trombone, an instrument that, at the time, only men played. Her father cheered her on, inviting her to practice in his gas station garage as he worked.

Her young confidence is evident in the letters she wrote to well-known musicians, asking for advice. When she was 15, she wrote to trombonist Robert Isele to ask for a lesson as she prepared for an upcoming contest. She assured him of her dedication: “I’ve written all this so you don’t think I’m just a beginner and so you won’t think that because I’m a girl, I’m not interested.”

Meanwhile, Scanzoni’s mother instilled in her an awareness of the burdens other people carry. She told her daughter to remember that she always had the potential to be “a sun ray” and that this was preferable to being “wind in their face.”

These twin attributes of self-confidence and compassion are what drove Scanzoni’s life-long passion for communicating. She once told me that readers were her sole motivation for writing. It wasn’t some specific idea or topic that inspired her but rather the potential of personal connection and the hope that her insight might make a difference for someone.

In fact, it was through a letter that her freelance writing career became focused on what later came to be called biblical feminism. Incensed by an article in Eternity magazine—it claimed that women were incapable of working in the church in the same way that men were incapable of working in the home—she took to her manual typewriter to fire off a letter to the editor. Before long she realized her letter was really an article; she sent “Woman’s Place—Silence or Service?” to Eternity, and it was published.

Later, she wrote a letter to Hardesty to invite her to co-write a book about “woman’s ‘place’ in the home, society, and church.” By the time they completed the manuscript for All We’re Meant to Be, which the New York Times later described as “a manifesto of evangelical feminism,” they were close friends, though they lived in different places. Scanzoni wrote to Hardesty in 1972, “I miss you very much. I wish right now you could join me for this cup of coffee. We’d have so much to talk about.” Later she remarked that she’d just heard “Lean on Me,” a song that reminded them both of the depth of their friendship.

Describing her friendships to me, Scanzoni used the image of a train. Some people get on and ride for a while, but at some point they get off. But there are others who get on the train, find a seat, and stay for the entire journey. Among her papers, I found notes on friendship for an adult education class at Indiana University in 1974, for a lecture at Shenandoah University in 1991, and in an outline for a future book. It’s too bad she didn’t get a chance to write it.

Scanzoni wanted people to know that even though we have “feelings of insecurity, apprehension, and alienation,” the “intense longing for human connection” is perfectly natural, a result of being made in the image of God. It is not enough to find intimacy with God alone; we also need to experience it with others.

She employed the biblical story of Jonathan and David to illustrate the depth of friendship she thought possible. She coined the term “one-soul relating,” drawn from 1 Samuel 18:1: “the soul of Jonathan was bound to the soul of David, and Jonathan loved him as his own soul.” For Scanzoni this illustrated intimacy, “relating at the deepest level of one’s being.” She believed this depth of unity is also evident in Jesus’ farewell prayer in John: “I in them and you in me, that they may become completely one” (John 17:23).

Scanzoni’s knowledge of sociology—early in her career she wrote sociology textbooks—helped her to reflect on the stages of friendship, elaborating on how profound connections require cultivation as well as sustained determination. The initial period of rapport, where there is a feeling of being on the same wavelength, is the easy part, she noted. The harder work of friendship is what follows. This is the development of self-disclosure and mutual dependency. In a lecture at Shenandoah University, she observed that the way out of loneliness is to open ourselves to another and not hold back.

Perhaps there is no better illustration of this than the experience Scanzoni and Mollenkott share in their preface to the revised and updated edition of Is the Homosexual My Neighbor? They write candidly about how Mollenkott, who was a lesbian, opened up to Scanzoni regarding her sexuality, how the revelation affected their relationship, and how Scanzoni came to terms with what her own public stance on sexuality would mean.

In a letter to Mollenkott, Scanzoni describes a time when the presence of God was palpable to her:

There, flashed through my mind the challenge you had presented, the burden you had shared, and I said, “But Lord, why should I? The costs would be so great and what reward would I have?” Immediately, I heard in my heart, “Well done, thou good and faithful servant; inasmuch as ye have done it unto one of these the least of my brethren you have done it unto Me.”

She knew she was called to carry this burden for her friend. She never looked back.

Scanzoni believed that one-soul relating friendships are the ones that enable us to reach our fullest potential. I imagine this may have been one reason she reached out to missionary and writer Elisabeth Elliot. She says she wrote to Elliot because she was concerned by the negative attention Elliot’s first novel, No Graven Image, was receiving. It wasn’t until her third letter to Elliot, however, that she confided that as a writer, she too knew “how lonely this work can be at times—particularly if one isn’t afraid to ‘rock the boat’ a little and speak out on controversial issues.”

Scanzoni and Elliot corresponded for about ten years—until, as Scanzoni put it, their differences became too great. I suspect their parting might have had something to do with a difference of opinion on the benefits of friendship. Scanzoni thought “enhanced creativity” was one of the benefits of intimate friendship, keeping us “from stopping short of our best, of getting discouraged, of giving up, of fearing to risk new things”—but Elliot did not. In one of her last letters to Scanzoni, Elliot wrote that she had all but “expunged the word” creativity from her vocabulary, preferring instead “authenticity.”

But Scanzoni knew from experience—and from her reading of published letters between friends—that one-soul relating bonds inspired creative breakthroughs. She was particularly impressed by the friendship between Eberhard Bethge and Dietrich Bonhoeffer, noting that they drew both spiritual strength and intellectual stimulation from each other. In her notes, Scanzoni refers to The Life and Death of Dietrich Bonhoeffer, by Mary Bosanquet. Later, she purchased John W. De Gruchy’s Daring, Trusting Spirit: Bonhoeffer’s Friend Eberhard Bethge, which she mentioned several times during our conversations. I can imagine Scanzoni responding to a treasured letter she received in much the same manner as Bethge, who wrote that one of Bonhoeffer’s letters was “a declaration of love from a friend, who rejoices in noting the shape of the relationship and takes pleasure in communicating it in the nocturnal letter to his partner.” Such open and honest love, he noted, was as a “wonderful reassurance.”

Scanzoni experienced a breakthrough in understanding for herself through an ongoing correspondence with a woman who, when working with LGBTQ people, had initially encouraged them to seek conversion therapy. When Scanzoni wrote to her years later, the woman (whose name Scanzoni withheld in her own writing) replied that she had changed her mind: new discoveries in biblical scholarship and further personal experiences led her in a different direction. Through their correspondence, Scanzoni also experienced what she called “a paradigm shift.”

I was late joining the Scanzoni train. I met her through the Evangelical & Ecumenical Women’s Caucus–Christian Feminism Today when she was the editor of their newsletter, Christian Feminism Today, and I submitted an article for publication. Before long, she was sending me books to review. Looking back many years later, I realized she had been nourishing my growth not just as a writer and scholar but as a person who, like her, worked at the margins, negotiating the in-between spaces of evangelical and mainline traditions. She connected me to voices who could speak my language and support my journey. When I moved from Oregon to Texas and was casting about for something or someone to help me stay afloat, I knew instinctively that she would understand.

I had sustained spiritual trauma that made it difficult for me to trust in or believe that God was good or loving, and I had mostly given up. Her faith had not suffered as mine had. The intimacy with God that she felt as a young girl when she explored nature, wandering among the trees in mountainous rural Pennsylvania, never abated. For her, God was a trustworthy friend. “In any true and deep friendship,” she said, “both friends change. Nothing can stay the same, because deep caring calls for responsiveness.” Even when she was exposed to fundamentalist churches and groups, places where she said she felt her wings had been clipped, she drew a distinction between those groups and her relationship with God. When events didn’t turn out as she hoped, she remembered something Corita Kent once wrote: “to believe in God is to know that all the rules will be fair and that there will be wonderful surprises.”

But Scanzoni never tried to convince me of her point of view—and we had some significant disagreements! She came alongside me and demonstrated faithfulness. In being present in my life each day, in not turning her back on me when I needed her, in sharing music that was meaningful to her (Kathryn Christian was one of her favorite artists) and that became a balm to me, she helped me to build back trust—slowly, over the course of years. If she could and would be there for me, it became possible to believe that God could be trustworthy as well.

She suggested I read Nelle Morton’s classic book The Journey is Home. What’s more, she put Morton’s idea of “hearing someone into speech” into action. She created the space I needed, and she listened. Now, reading from my journal at the time, I found where I wrote this: “Letha is leading me step-by-step back to a life that feels meaningful and joyful. It has been a long time since I’ve felt this satisfied with my life.” She urged me to write as another way of working through my loneliness.

We discussed several collections of letters, but one stood out: Letters from Max: A Book of Friendship. She thought I might resonate with the professor-student relationship between Sarah Ruhl and Max Ritvo, as I was a professor at the time and remained in contact with former students. I read it through a different lens, though, realizing that like Max, whose health was in rapid decline, Scanzoni was aging. While I cherished the friendship we were creating, I could feel the inevitable brevity of it pressing in on me.

When she died, I pulled Letters from Max off my shelf, flipping through the pages, recalling how it spurred some of our conversations. At one point Max writes that Sarah’s letter is “silver, in the sky,” and that she was so deep in him that his writing sometimes felt like her voice, her language coming out of him. Reading this now, I can almost hear my friend’s voice whispering in my ear, a beautiful example of one-soul relating.

People who visited Scanzoni in her home and shared a meal with her know that she liked to share a prayer or sing together before eating. During my visits we sang a song she wrote to the tune of “Morning Has Broken.” It illustrates how integral friendship was to her:

God of creation, life’s celebration,

Giver of friendship, author of love:

Come to our table, bless us, enable

Our lives to show fully your life from above.Moments to treasure, sorrow and pleasure,

The gift of each other to nurture and tend;

Love never greater, Christ, our example,

Life laid down freely to care for a friend.Thank you for guiding. Thanks for providing

Food for the body, strength for the day.

Sustain and nourish. Make our souls flourish

Through life together, God, lead the way.

People may assume Scanzoni thought her greatest achievements were co-writing All We’re Meant to Be and Is the Homosexual My Neighbor? They would be only partially right. What mattered most to her wasn’t what the accomplishments meant for herself but rather the difference her work made for others. Those bulging binders and files full of letters—which I hope someday will come to light—are a testament to her passion for life-changing connection: one-soul relating. “This,” she said and lived, “is the gift of our lives.”