Moltmann the teacher

Studying theology with him offered me new possibilities for justice and abundant life.

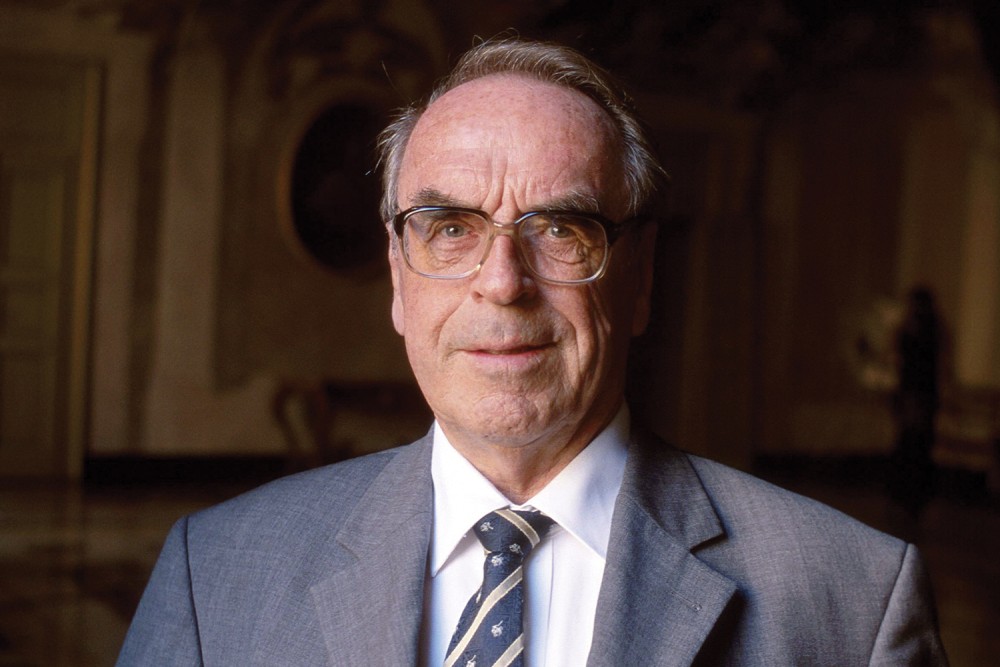

Theologian Jürgen Moltmann (Basso Cannarsa / Agence Opale / Alamy)

After finishing my master of divinity, I returned to my home province of Córdoba, in Argentina, to live with my parents while figuring out my next steps. I taught in a small Bible institute in Córdoba City and helped out at a local church. I felt called to be a theologian, and one option was to pursue a doctorate in Buenos Aires, at the Protestant Faculty of Theology (ISEDET). But the theology of Jürgen Moltmann would not let me go.

I had first encountered the German theologian, who died in June, in his sermons collected in The Power of the Powerless. I found them thrilling. Here was a theology that took the triune God seriously in a way that could be preached and lived. I had devoured his early works, Theology of Hope and The Crucified God. In them I discovered a hope against hope that was very different from blind optimism: it was hope based in the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus Christ, and it opened up new possibilities for justice and abundant life, starting now. At the same time, his attentiveness to the cross functioned—much as the theology of the cross in Martin Luther’s Heidelberg Disputation does—as a way of discerning the structure of reality more clearly, in the midst of many distractions.

I consulted with my former professors: Did they think it was possible for somebody like me to study with Moltmann? They replied that it doesn’t hurt to try. So I found a way to write him a letter.