Microbes in the manger

God is humbly present in every living creature. Maybe closer than we’ve imagined.

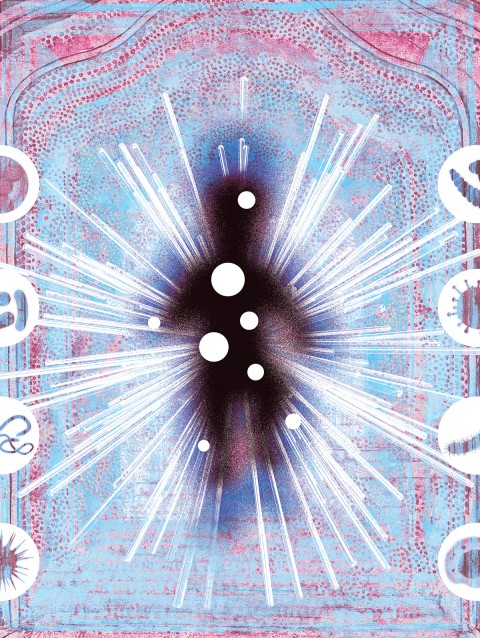

Century illustration by Daniel Richardson

When I was a child, a few weeks before Christmas each year my family would gather with friends and neighbors at a nearby barn. The barn was home to gentle trail-ride horses, a Shetland pony known for its bite, and a scattering of sheep, goats, and rabbits that made up a petting zoo. On the floor of the barn, hay bales would be arranged as seats, centered around a wooden rack. Us children would don towels on our heads cinched with neckties, along with bathrobes cut to fit our small frames. As an adult read from Luke’s Gospel, we would act out the story of Christ’s birth, a narrative made real by the smell of hay, the bleating of sheep, and the fermented scent of ruminant manure.

I doubt anyone in that barn knew it then, but our gathering was in line with a tradition that began nearly 800 years earlier, in the Italian hill town of Greccio. It was there that St. Francis of Assisi was inspired to celebrate a remembrance of the birth of Christ in a living tableau: a hay-filled crib with a donkey and ox beside it. The event is considered the first living nativity, and as St. Bonaventure describes the scene in his biography of Francis, “the saint stood before the crib and his heart overflowed with tender compassion; he was bathed in tears but overcome with joy.” Elated from this experience of Christ come near, Francis preached to the crowds that gathered about the “Babe of Bethlehem” who was born a “poor King.”

For Francis that crib was a place where God’s humility poured forth in radical connection, the Creator of all things coming to dwell among his creatures. To set a vision of the Christ Child among animals was not simply a nice medieval morality play, a faith-filled entertainment based on a historically dubious rendering of Christ’s birth. Francis’s imagination followed the implications of Christ’s birth to include the animals that, though not mentioned in the scriptural accounts, were inevitably there, perhaps too obvious to even mention. To make them visible was to broaden the view of Christ’s coming into the world, an Immanuel moment that extended God’s being-with beyond the bounds of the human.