Kindled in the wild

Many young people love going to church camp. How does it shape their spiritual lives after they return home?

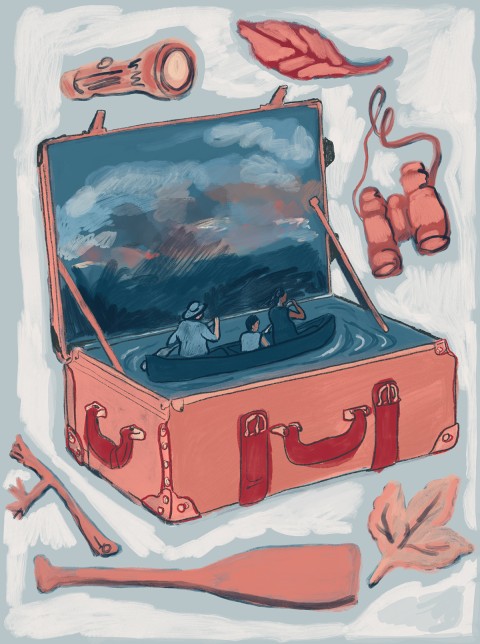

illustration by Martha Park

My teenage summers were spent at camp, exploring the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness in northern Minnesota and Quetico Provincial Park in Ontario. I remember the moment I realized I was the only person of faith among a group of 16-year-old girls and our counselor. I had no judgment, only gratitude for all the people and experiences who had fostered that faith deep in me. I was able to make theological connections and continue practicing my faith out there in the north woods because my parents and myriad other saints had handed down the faith to me for years.

I’ve wondered about the connections between church, camp, and home for most of my life. Youth ministry scholars tend to dismiss camp as mere fun and games and critique it for being theologically shallow, as do many of my pastoral colleagues. But what if we envisioned camp as a space to train young people in the language of faith and to spark faith conversations, along with other practices, in the home? This is exactly what the Rhythms of Faith Project seeks to do: to use camp as a catalyst for family faith formation.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

When I was in graduate school, I wrote theological papers about outdoor ministries. I tried to cite quantitative data on the impacts of Christian camps, but no one seemed to have any. Camp shaped me, as it did the children and youth I have helped send to camp, so I am elated to see that serious research is now being done on the power of camp to influence young people, their families, and the church.

For many years we had little data on the impact of camps generally, let alone Christian camps. That has changed dramatically in the last 25 years, and there is now a growing body of peer-reviewed research. The American Camp Association has led the way, exploring the lasting impacts of camp and the way camp experiences prepare young people for life. These studies demonstrate that overnight camp experiences have significant and lasting effects on multiple youth development outcomes, including affinity for nature, independence, self-confidence, and spirituality. They also conclude that summer camp is one piece of a larger developmental ecosystem—a finding with great implications for church camps. Though it may offer unique benefits compared to other settings, camp is best understood as a setting that can complement young people’s other life experiences.

The leading scholar of Christian camps is Jacob Sorenson, director of the Effective Camp Research Project and author of Sacred Playgrounds: Christian Summer Camp in Theological Perspective. His research is based on qualitative interviews and survey data from more than 20,000 campers and 9,000 parents from more than 80 Christian camps across the United States and Canada. Sorenson has uncovered what he calls the five fundamental characteristics of Christian summer camp: safe space, participatory, relational, unplugged from home, and faith-centered.

Christian camps share some of the same outcomes that ACA uncovered across the industry, such as independence and self-confidence, but participants also consistently show significant and lasting growth in Christian belief, spiritual practices, connection to Christian community, and—perhaps most importantly—an understanding that faith matters in their lives.

The Rhythms of Faith Project builds on this research. Sorenson codirects the project with Rob Ribbe, longtime director of Wheaton College’s HoneyRock Center for Leadership Development and a recognized leader in researching evangelical camps. The project thus brings together the two leading scholars in Christian camps for a five-year, nationwide, ecumenical initiative that partners with Lutheran Outdoor Ministries, United Methodist Camp and Retreat Ministries, and the Christian Camp and Conference Association. It is funded by Lilly Endowment Inc. (I serve on the project’s advisory team.)

Through action research, the team is exploring how camps can partner with parents and churches in faith formation. What conversations about scripture, prayer, and faith that start at camp could families continue back home? In what ways could camps support parents and grandparents in partnering with their youngsters in faith formation throughout the year? And what could congregations, also vital parts of the ecosystem, learn from the camps?

I’ve also wondered if parents even want help from camps in handing down their faith. Isn’t this their own responsibility, or possibly that of pastors and Sunday school teachers? Sorenson explained to me that “increasingly, camps are taking a leading role in faith formation, moving from parachurch ministries where Christian leaders send children for fun and fellowship to training centers that influence the home and the church, oftentimes serving as entry points for faith formation.” The team’s research suggests that parents are eager to receive resources and training from camps. In a survey of more than 1,200 camper parents reflecting on summer camp experiences a year later, 63 percent indicated that they were highly important factors in influencing their family’s faith practices. In parent focus groups, parents consistently expressed an interest in receiving help from the camp to continue the positive impacts in their home. Parents also reported that camp had a significant impact on their families’ “conversations about God,” a key factor in forming long-term faith.

The parent survey was just one part of a robust exploratory phase of research designed to identify the most promising strategies of overnight Christian summer camps to influence faith formation in the home. The team also surveyed camp directors from across the networks of LOM, UMCRM, and CCCA, following up with 20 interviews to explore some of the most unique and promising strategies. Researchers then visited 11 camps during summer 2024 to see the strategies in action and engage campers, parents, church leaders, and summer staff in focus groups. Having identified the most promising strategies, the team will spend the next few years testing and refining them at selected camps, while sharing the findings with practitioners.

One of the most important observations from the Rhythms of Faith Project is that “Christian summer camps are broadly effective at impacting the personal faith and practices of participants, but they frequently lack a holistic approach to faith formation aimed at influencing faith beyond the camp experience.” This is something the team seeks to address by sharing the most promising strategies. As codirector Ribbe said, “camps cannot serve as the sole source of faith formation or an outright replacement for the permanent spaces of home and church. They have the opportunity to be training centers for young people and catalysts for faith formation in the home.”

The strategies begin with a consistent philosophy of ministry: faith is not compartmentalized from other programs but rather is integrated into all aspects of camp. An LOM director said, “We try to incorporate faith throughout everything. We say faith development is part of the day 24/7.” The campers also recognized it as a faith immersion experience, as if faith were in the very air they breathed. At Camp Glisson, a UMCRM camp in Georgia, a camper said, “It feels like God is all around us, like with us wherever we are.” These camps focused on creating a culture of leadership development and lifelong discipleship. They sought to facilitate leadership experiences that transferred back home.

Camp also must be recognized as a temporary community functioning in partnership with a larger ecology of faith formation that includes the home and local church. Here again, the notion of an ecosystem is important. One of the common critiques of camp is that it is not part of an ecosystem so much as a stand-alone “mountaintop experience.” In their conversations, the researchers heard camp professionals wrestle with this concept. One CCCA respondent talked about how they intentionally “lowball” the mountaintop aspect of camp because they do not want their campers overidealizing the “huge God moments” of a camp experience.

The most robust models that incorporate camp into family faith formation include strategies focused on three audiences: campers, parents, and church leaders. They also consider more than just the camp experience, including strategies to prepare the participants before camp, equip them during it, and follow up afterward.

One CCCA camp restructured mealtime prayers from a playful, camp-centric approach to family-style prayers in individual camper groups at their tables in order to teach a transferable practice. At a UMCRM camp, after each activity campers gather in groups to debrief the experience, asking questions like, What did we just experience? Where was God in the experience? How will you carry this with you?” This helps the group process the experience and connect it to their faith and life away from camp. With a nod to the unplugged component of camp, very few activities took place indoors, intentionally facilitating interaction with the outdoors and disconnection from electronic devices. The campers gave glowing reviews of the tech-free environment, saying that they “like it better” than when everyone is on their phones and noting that “people look me in the eyes.”

Hidden Acres, an Evangelical Free Church of America camp in Iowa, taught a simple but unique method for personal devotions, using the acronym CAMP: choose a passage, ask questions, make it personal, and pray. Campers were trained at camp and encouraged to use the CAMP method on their own after they returned home. To emphasize this, the staff included a second week of devotions in the devotional booklet given to each camper, to be used after camp. After hearing the initial findings of the Rhythms of Faith Project, the camp added an additional resource in 2024. When parents arrived to pick up their children at the end of the week, the camp director handed them each a family devotional book and encouraged them to continue the practices learned at camp in the home.

This was one of many strategies these camps adopted to engage, partner with, and provide resources for parents in supporting the faith lives of their children. At Caroline Furnace, a Lutheran camp in Virginia, parents learned the evening devotional method that campers used at camp (based on Rich Melheim’s Faith5), even practicing it on-site with their children to prepare them for evening devotions in the home. The most robust closing program was an all-day parent training session at HoneyRock in Wisconsin. The parent experience includes a ten-minute, one-on-one session with the child’s cabin leaders, who share a report on what the camp session was like for their child, everything from highs and lows to growth and lessons learned. At Chestnut Ridge, a UMCRM camp in North Carolina, parents receive an invitation to participate in a family program called Seeds of Faith. Designed to build on the camp experience, this program provides a weekly dinner for families while empowering them in family faith formation.

When it comes to partnering with churches, the research indicates that the partnership must be reciprocal. At Rainbow Trail, a Lutheran camp in Colorado, each day a different group of campers takes a leadership role. They establish a fun theme for the day, make creative connections to the Bible study, and plan and lead two worship services. These campers learn leadership skills in a way that is designed to carry over into their home church. One visiting youth minister marveled, “Now I understand where it comes from,” referring to how, after attending camp, the young people in her congregation are always willing to step up and lead programs and worship services at church.

Several camps directly engaged church groups and their programs at camp, such as confirmation camp programs in the Lutheran and Methodist traditions. Camps held church retreats for youth, adult groups, or church leadership groups. One camp had partner congregations hold Sunday worship at camp instead of in their church buildings. Finally, camps provided churches with devotional materials, discussion guides, and take-home resources, which helped reinforce the sense of a reciprocal partnership with their partner churches.

What if campers do not have a home church? A CCCA camp surveyed campers on the last day of camp to see if they were unchurched and wanted a relationship with a church. If they did, the camp prompted a church in the camper’s hometown to follow up with the family after camp. A denominational camp adopted a simplified version of this strategy: It provided campers with a list of local churches and dates for family events in the weeks after camp.

The camps with the most promising strategies practiced adaptive leadership, which is the crux of the matter. In camping, adaptive leadership looks like continually learning and evaluating. There was a humility and curiosity that set some camp leaders apart from others. They wanted to learn and grow, rather than continue doing things as they had always done them. Envisioning camps as training centers and doorways to church engagement rather than places to send kids is a paradigm shift for many, but it’s a necessary one, especially for coming generations.

It’s a timely coincidence that this camp research is being reported just when Jonathan Haidt’s The Anxious Generation has landed on the desks of so many of us who care about childhood and youth development. “My central claim in this book,” writes the social psychologist, “is that these two trends—overprotection in the real world and underprotection in the virtual world—are the major reasons why children born after 1995 became the anxious generation.”

One of Haidt’s antidotes is to “draw on wisdom from ancient traditions and modern psychology to try to make sense of how the phone-based life affects people spiritually by blocking or counteracting six spiritual practices: shared sacredness; embodiment; stillness, silence, and focus; self-transcendence; being slow to anger, quick to forgive; and finding awe in nature.” When I read this I wanted to exclaim, “This is what churches and church camps have been doing forever!” As Sorenson is fond of saying, “camp is one of the last places in existence where young people put down their devices for more than a few hours at a time, and they are excited to do so!”

Camps are great at fostering organic conversations that go below the surface. Whether on a hiking trail, paddling a canoe, stirring embers of a campfire, or lying in bunk beds when the lights have gone off, the settings and relationships lend themselves to asking and discussing the big questions. Research shows that parents and other primary caregivers take the lead role in faith formation, but there are other key players as well. Both camps and churches can help train youth and young adults to speak the language of Christian faith, language that can then be spoken among family members. Faith formation happens throughout an entire ecosystem.