False gods of war

In Trump’s Situation Room, as on the fields of Ilium, those who wage war seem unable to experience the violence they inflict as real violence.

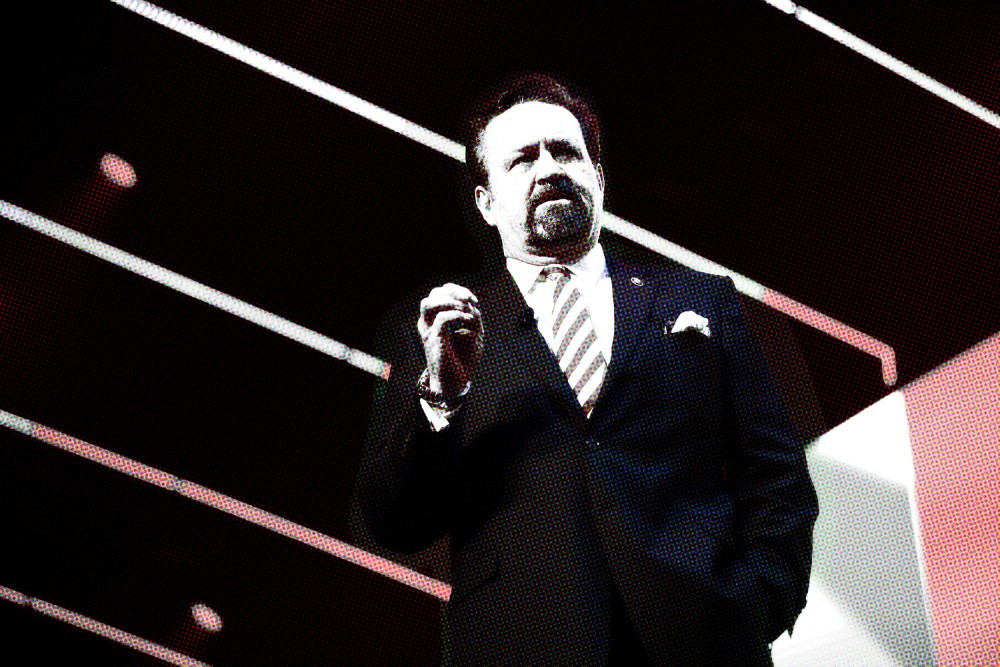

Sebastian Gorka (Source image: Gage Skidmore / Creative Commons)

Sebastian Gorka, the senior director for counterterrorism for the White House National Security Council, is regaling a sparse audience at February’s Conservative Political Action Conference with a story of what it’s really like to work for President Trump. His signature goatee and booming Mitteleuropean accent punctuate his performance as the pompous blowhard; his we’re-all-in-on-the-joke tone makes him one of the few Trump surrogates to truly follow the master.

“Smile every day,” he shouts like he’s bringing an arena to its feet, channeling the mood of Trumpism’s triumph. “Revel, revel, revel in what you have done!”

He launches into a story about a top-secret meeting—“everything has been declassified,” he reassures the rapt audience, drawing them into Trump’s inner circle—in which the President was informed of what Gorka calls an “ISIS terrorist enclave” in Somalia.

“President Trump looked up from the Resolute Desk and said”—here Gorka pauses for effect—“‘Kill them.’” The crowd laughs and cheers. Next he describes a pivotal scene: he sits with the generals in the Situation Room, eyes glued to the big screen to watch the killings Trump has ordered. “It’s like I’m in an episode of 24,” he gushes. “Or a Jason Bourne movie!”

The story slides further into fantasy—we’ve all gone from being with Gorka as he watches a drone strike to being with Gorka as he pretends to be a TV character watching a drone strike—and moves quickly into the grotesque. A video plays on two screens behind him. Grainy drone footage in black and white. A figure walking alone on a scrubby hillside. “Remember this is not a movie,” Gorka has to remind us, “this is real life.” But he sounds just like a character on 24 or The Bourne Identity, and it’s no longer clear what the difference between real life and a movie would even be.

“This is what President Trump did to him.” The screen flashes white. Then we see the same hillside, the scrub flattened. The figure is gone. The crowd cheers, whistles, claps.

We’ve just watched a snuff film, but Gorka has invited us not to see the terrible things before our eyes, but to pretend we were sitting with him in the Situation Room, proud, clean, and in fine clothes. Watching on my own screen at home, a woman’s arms, draped in red, white, and blue sequins, shake with glee in front of the camera.

“Smile and be happy,” Gorka says, and the room obeys. “You won.”

Sebastian Gorka is no epic hero, but he offered, in his clownish way, a Homeric lesson in force’s self-veiling logic. In book V of the Iliad, Ares, the god of war, is wounded by a human warrior, prompting him to rush home to Mount Olympus. It turns out “the god whose thirst for war is never sated” is unable to bear this brief glimpse at the reality of war. His wound—a scratch, really—has opened his eyes for an instant to what war really is. “Terrible things,” he groans to the other gods, “gruesome corpses.” Ares prefers war to be spectacle, entertainment, shrouded in fantasies of handsome heroes clashing for eternal glory. So he flees the battlefield for the hazy paradise of Olympus. “After all,” the narrator tells us, “he was not mortal.” His servants bandage and bathe him, and now safe from having to see the gruesome corpses, the god of war is back to his old self. “Impetuous Ares” reclines clean and in fine clothes, “feeling proud of his magnificence.”

The philosopher and theologian Simone Weil thought the Iliad was a kind of pre-Christian revelation of divine truth, specifically the truth that war is not glorious or good but senseless, stupid, ugly, and dull. Homer’s famous similes, in which advancing and retreating troops are likened to the tide, or storm clouds rolling in, or an avalanche, are for Weil illustrations of how the force of war reduces both victor and vanquished to unthinking matter, mindlessly obedient to the law of the stronger. The Iliad depicts war not as an arena where men are made and glory is won, but as a dehumanizing, meaningless waste of human life. The poem is an early glimpse of Christian truth, according to Weil, because it so clearly depicts what she calls “force,” that which God utterly refused by becoming incarnate as a helpless infant and a murdered victim.

Weil doesn’t mention the moment when Ares flees the battlefield, but the scene reveals an even deeper truth of war: how war’s violence has a way of veiling itself, how those who kill and destroy seem to experience the violence they inflict as something other than violence. Even Ares, the lord and master of war, flees the truth of war—that it is nothing but a senseless heap of gruesome corpses—to dwell in his childish fantasy of war as entertainment.

In the Situation Room, as on the fields of Ilium, those who wage war seem unable to experience the violence they inflict as real violence. This is why Homer depicts the god of war as the character least able to bear the sight of gruesome corpses, the one who, more than anyone, shrouds his eyes in childish fantasies. War veils itself in fantasies of glory, honor, strength, or mere entertainment. The point of the Iliad is to tear down these veils with a sickening monotony of spilled organs and severed limbs. Real strength, the epic suggests, lies in the ability to look through the glorious veil and see the gruesome corpses lying beneath.

This is why Simone Weil saw the epic as a precursor of the Christian gospels. Like the Iliad, the gospels impel us to disbelieve the lies war tells about itself. They impose on us the nearly impossible demand to see the terrible things right in front of our faces.

In the book of Acts, Paul stands on a hill dedicated to Ares and preaches the good news of an unknown god: a god so unlike the god of war as to be unknowable on his hill. This god is found not by marveling with the crowd at Caesar’s victory marches but by looking squarely at war’s real work: a shivering infant clutched by a homeless refugee, a gruesome corpse nailed to a tree on the side of the road.