The consolation of studying theology

Theological education is precarious, inconvenient, and uncomfortable. So why do students keep enrolling?

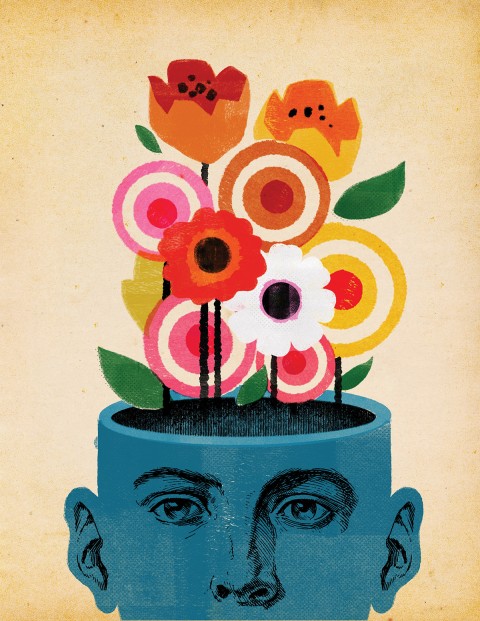

Illustration by Jay Vollmar

What does it mean to be a seminary student in times like this?

This is the question I pose to students as they reach the conclusion of their formal theological studies, the MDiv capstone seminar. Classes like this appear in seminaries across the North American landscape and have since the earliest days of American theological education. Those early capstones were often taught by the seminary president, providing one last opportunity to impress the school’s most treasured convictions on the hearts and minds of its students. In the 20th century, the model of a sage conferring wisdom gave way to a more bureaucratic model, one that tracked with changes in American religious life. Charged with preparing pastors for the denominations that provided these schools with both students and resources, the aspirations of the final class became linked to ordination requirements, their “statements of ministry,” and quite often an orientation toward practical competencies.

Readers of this magazine won’t need much convincing that we are living in different times. Seminary presidents are usually tasked not with teaching students but with raising the funds that make such teaching possible. The links tethering seminaries and their founding denominations have also changed. Professors tend to be hired without concern for denominational allegiance. The number of students sent to seminary by congregations—and certainly those whose tuition is paid by congregations—also appears to be declining. And there is a dampened interest in serving local parishes, with various forms of chaplaincy emerging as the preferred career path.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

For all these reasons, the meaning and purpose of seminary in times like these is an open question. In the classroom, rather than pretending like I know the answer, I pose the question to the students who’ve chosen to spend all this time reading, writing, thinking, conversing, and training in the practical arts of ministry. What has it all meant for us as spiritual creatures?

This course offers me a research opportunity, and I’m learning so much from them. In one recent class, a student uttered a phrase that crystallized an insight about seminary that I’ve been pondering ever since. They said, “I’ve received a lot of things by coming to seminary. But comfort is not among them.”

In this case, the discomfort concerned our felt sense of belonging. I teach in a liberal, increasingly multireligious seminary, and while most of our students embrace these commitments in principle, tensions emerge in living them out. Christian students with more traditional convictions sometimes feel uncomfortable with the more progressive politics and activist orientation of other students. Jewish, Buddhist, and pagan students sometimes feel uncomfortable being at a Christian seminary, no matter how pluralistic it aspires to be. Add to these all the other intersectional identities that students and professors bring into our classrooms, and it’s no wonder that theological study here doesn’t exactly feel like warm bathwater to any of us.

This was the insight that slowly emerged in our capstone class. As one student after another confessed their discomfort, it became clear that while the identities and convictions that accompany each of us are often quite different, the sense of discomfort we feel is shared.

This led me to wonder: What is it about studying theology here and now that generates such discomfort? And if the study of theology is so uncomfortable, what keeps students coming back to these classrooms? Is there perhaps a deeper consolation lying just below the surface of these discomforts?

There are certainly ample reasons for discomfort. Students are navigating a wider array of differences than perhaps any cohort of seminarians ever has. In addition, theological education is undergoing vast changes in the modes of teaching and learning—the shift from predominantly in-person, residential education to classrooms that now span space and time. This has exponentially increased access to theological education, but it also means that more traditional ways of relating to one another, of forging the ties that bind us together as a community, are being reimagined on the fly. And that’s uncomfortable.

There are discomforting forces at play beyond our walls, too. The religious landscape in North America is changing rapidly, and that means the kind of careers seminary students hope for when they graduate are increasingly precarious. Can local congregations support a full-time minister? Will hospitals continue to fund their spiritual care departments?

And even if they do, will anyone listen to what spiritual leaders have to say? To my mind, this concern is even more fundamental than the very real economic worries. It captures what I think we all implicitly know: that religion and theology have become broadly illegible in a world that increasingly conflates value with price, that reduces the pursuit of goodness into a polarized political struggle between us and them, that thinks of truth—if it thinks at all of truth—merely as bits of information algorithmically delivered to ideological echo chambers designed to constrain our attention, confirm our uninterrogated presuppositions, and soothe us into a self-

satisfied conformity and spiritual numbness.

These signs of spiritual regression are, unfortunately but also unsurprisingly, evident within religious and educational institutions themselves. Valparaiso University, a Lutheran school in Indiana with a long history of leadership in theological education, recently announced a proposal to discontinue its theology major, along with more than a dozen other programs with diminished enrollments. Denominations and chaplaincy accrediting bodies are questioning the value of theological study, in some cases arguing that religious leaders are being overeducated in traditional MDiv programs. They recommend that the vigorous study of ancient religious texts, of history, and of contemporary constructive theologies should be replaced by more practical, skill- and competency-based models of formation. The contention is that most of what happens in a 72-credit MDiv degree—all that reading, thinking, writing, conversing, and contemplating—is superfluous to the concrete tasks of caring for souls and leading religious communities.

It’s no wonder that students—not to mention professors—are feeling some discomfort. These are discomforting times. To feel this means we’re viscerally in touch with the spiritual dynamics pulsing through our world at this moment.

Theological study, if we’re doing it right, doesn’t avoid the crises of our world. It interrogates them at the deepest level.

So why on earth are students signing up to endure the discomforts of the classroom, the precarity of their job markets, and the less-than-subtle suggestions—even from other religious leaders—that the intensive study of theology is an unpleasant, arcane, impractical waste of time? Is there some hidden consolation for studying theology?

To frame the question this way is already to treat theological study—all this reading, thinking, writing, conversing, and contemplating—as a spiritual practice.

In the early sixth century, amid the ruins of the Roman Empire, Boethius wrote The Consolation of Philosophy while imprisoned and awaiting execution. Boethius found spiritual nourishment from reading, thinking, writing, conversing, and contemplating philosophy. In his book, he personifies this through the character of Lady Philosophy, who—through a long dialogue in his prison cell—reminds him that philosophy, the love of wisdom, promises more than just to guide human beings through the vicissitudes of what Shakespeare’s Hamlet would later call “the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune.” The act of philosophizing can even help one flourish amid that tumult. It can make one happy, even in the worst of times.

A thousand years later, the Spanish mystic Ignatius of Loyola invoked the notion of consolation in the Spiritual Exercises. This comes amid his instructions on the discernment of spirits, in which he tells us that the key to discerning the difference between a temptation from the evil spirit and an edification by the Holy Spirit is to look closely at how the soul is being affected. If a movement in the soul increases hope, faith, and charity, it is a consolation from the Spirit of God. If a movement in the soul “moves one toward lack of faith and leave[s] one without hope and love,” it is, by contrast, a desolation with roots in that which opposes God.

As our capstone seminar reflected on the nature of our collective discomfort in studying theology here and now, the spirit I discerned was not at all lacking in faith, hope, or charity. Quite the opposite. I heard students grappling with all the realities facing seminarians, religious leaders, and human beings of good will in this turbulent moment in American religious life and the life of our world. Their discomfort—our discomfort—stems from a profound commitment not to look away from these realities, not to avoid the unpleasantness and precarity, not to take false comfort in fantasies that soothe us into an unresponsive slumber. Friedrich Schleiermacher calls this stance a “holy sadness,” one rooted in a deep faith and hope that taking a good, hard look at reality, even its troubling bits, puts us in touch with the infinite living God.

Such faith and hope are also evident in the fact that each of these students is continuing to study theology and to preserve the possibility that others long after us might go on to study theology—despite the discomforts of doing so, the apparent uselessness of doing so, the illegibility of doing so for a world intoxicated with costs, benefits, and productivity. It is here, in this mysterious conviction that we all tacitly share by virtue of being here and doing what we do, that I think my students and I find the consolation of theology.

Abraham Joshua Heschel tells a story of a band of reckless, novice mountain climbers who suddenly lost their footing and fell into a snake-infested pit. “Every crevice became alive with fanged, hissing things,” he writes. The men started to kill the snakes, one after another, but for each one they killed, “ten more seemed to lash out in its place.”

Amid this chaos, “one man seemed to stand aside from the fight.” The others reproached him for not doing his part. What he was doing seemed impractical to them; it seemed to be avoiding the real and present dangers that beset them all. It seemed like he was staring off into the clouds.

It seemed this way because what he was actually doing was illegible to them. All the social and material pressures were driving him not to think but to get back to the more pressing business of killing snakes. But rather than succumb to this temptation, the man who no one else understood sought to make himself and his purposes legible: “If we remain here, we shall be dead before the snakes. I am searching for a way to escape from the pit for all of us.”

Could contemporary seminarians, those who study theology intensively in this time, be like this man?

The reading, thinking, writing, conversing, and contemplating that we do in theological schools can seem to many in our world—even to other religious leaders, even to ourselves sometimes—like foolishness. Or even worse, like an irresponsible diversion from the more pressing task of growing churches, of organizing social movements, of defending democracy, of protecting the environment. Of killing snakes.

But if we’re doing it right, then all this reading, thinking, writing, conversing, and contemplating is not a way of avoiding the multiplying crises of our world. It’s rather a way of interrogating them at the deepest and most capacious level, of looking for ways to remain human and humane as we navigate them. And God willing, it reveals new ways to escape from the fearsome pits in which we find ourselves, new paths that would never even appear to us if we weren’t formed by thinking alongside Job and Paul Tillich, Monica Coleman and Boethius, Linn Marie Tonstad and St. Thomas Aquinas, Teresa of Ávila and James Cone. The Buddha, the Bhagavad Gita, and the Bible.

These treasures confer upon students of theology powers of perception that we then bring into the hospital rooms, prison cells, church board meetings, community organizing strategy sessions, classrooms, and art practices where we do our work. And this changes our work. Instead of simply hacking away at the snakes, the student of theology reads, thinks, writes, and contemplates about what’s really going on here and wonders whether there might be other ways out. And they do all of this with a vast chorus of voices that help them to see more than first meets the eye.

This might sound superfluous to the concrete, practical tasks of ministry and activism. But I don’t know how we could approach any of these tasks responsibly in this moment without the wisdom of our most perceptive spiritual and religious ancestors.

This study of theology thus offers guidance in turbulent times. But it also changes us. To study theology is a reminder that we humans are more than comfort seekers. We are more than utility maximizers, more than doers of good deeds and builders of just societies, more than makers of beautiful or scandalous or politically charged art objects. Of course, humans are blessedly all those things. And we are also spiritual creatures who can perceive the movements of the living God in our midst and can, miraculously, even respond to those movements.

The point of all this theological study, I think, is to remind us of this truth. Better yet, it is to put us in touch with a way of life that is elevated by the sustained attention to this truth. This counts as a consolation because it points us to that deeper wellspring of life and wisdom that, throughout the ages, promises to orient our consciences, to enflame our religious imaginations, and most of all to provide occasions for flourishing and joy amid the tumult.

Perhaps this is why students keep coming to seminary, despite all the discomforts. It certainly keeps this professor in the game. And while there is no quick fix for dealing with all the menacing snakes, theological study might keep us human as we face them.