Clarissa and her flowers

Reading The Hours in my husband’s hospital room, I was stunned by the novel’s incarnational imagery.

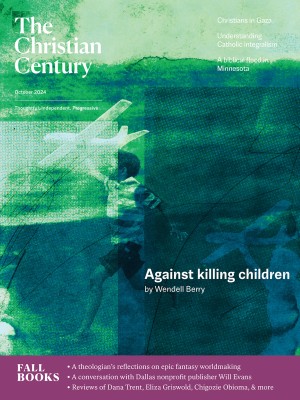

(Illustration by Isabel Seliger)

In June 2023, my husband, barely 52, was scheduled for surgery to repair a ruptured aorta. Staring down the prospect of spending hours upon hours in a hospital waiting room, I wanted a book that would absorb me. I picked up a battered paperback of Michael Cunningham’s novel The Hours from a Little Free Library in my green neighborhood park. It was the 25th anniversary of the novel’s publication, so it seemed a good time to revisit it.

“Are you sure you want to be reading that?” my older brother said. “That doesn’t sound like the kind of vibe you need right now.”

His doubt that The Hours would be a good hospital read stemmed from the very serious thematic spindle around which this lauded novel is wrapped. The book is famously an homage to, and evocation of, Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway, a novel documenting the one long day of the protagonist’s preparations for a party. Perhaps Cunningham’s most audacious turn is to make Woolf’s own life and suicide one narrative strand in its tripartite structure. There are still further echoes: another subplot focuses on an aging New York bohemian woman’s efforts to celebrate the triumph of her old friend and brief long-ago lover, who has just been awarded a major literary prize but is dying in the final stages of AIDS. The third snaps back to 1950s Los Angeles, tracking over the course of a day the advancing anxiety of a suburban housewife, who is uncertain about sexuality, marriage, motherhood—and just wants to find a little time to read.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Three separate days, linked. It was one of those three narrative strands, in fact, that I was thinking of when I saw the book poking off the shelf in the park that June afternoon, midway through a run with the dog.

When I saw the book I immediately recalled the 2002 film adaptation, in which Julianne Moore plays the LA housewife crawling bleakly through a sunlit day. But it was Clarissa, the New York publisher and bohemian, who had won me. Played by a lanky and vibrant Meryl Streep, Clarissa charges through a gorgeous New York, determined to ensure that the party for Richard is the tribute to his talent, his very being, that their poignant personal history deserves.

There’s a moment when Streep’s Clarissa bears down hard on the pavement, a sheaf of flowers in hand, off to visit her dying friend, an image of joyous unstoppable force. That was the moment I was thinking of when I took the book in my hand.

In 2002, when I first saw the film, I was still a newlywed, living in a rented townhouse in Northern Virginia, before gentrification pushed us into Maryland. My husband regularly played in a heavy metal band in an archipelago of working-class Baltimore bars, loud places I hated, so on Saturday nights I pulled out my post-9/11 hobby—knitting—and stayed home, watching movies that I rented from the mom-and-pop video store around the corner.

The image of Meryl Streep charging down New York streets with her flowers stayed with me. It was an icon, even, something that, whenever I faced a hard task or a dark hour, I called upon in myself. In those early years before children, I suddenly had to face the revelation of my mother’s dementia, and after years of our family’s denial, the unavoidable evidence of her rapidly advancing decline. Clarissa and her flowers spoke to me of joyously resolute strength in the face of impending disaster.

Imagine, then, what it felt like to sit in the windowless basement waiting room at Suburban Hospital and see the words lift from the page and enflesh that image of Clarissa in a way that a mere film never could. Here’s how that sidewalk image of her appears in the book, framed by the perspective of an acquaintance who sees her on the street:

She still has a certain sexiness; a certain bohemian, good-witch sort of charm; and yet this morning she makes a tragic sight, standing so straight in her big shirt and exotic shoes, resisting the pull of gravity, a female mammoth already up to its knees in the tar, taking a rest between efforts, standing bulky and proud, almost nonchalant, pretending to contemplate the tender grasses waiting on the far bank when it is beginning to know for certain that it will remain here, trapped and alone, after dark, when the jackals come out.

An exuberance tinted with dread. And that was about to be a lot more relevant to me within hours, when the surgeon called while I was driving home on the Capital Beltway to tell me that there were a few things he found “troubling.” There would be transfusions; my husband would be ventilated, intubated, and on a continuous renal therapy machine. Ultimately, the surgery that saved his life had caused a stroke to his spinal cord, leaving him paralyzed below the waist—something he would not even be awake enough to know for another month.

It was then that I came to pay attention to the novel’s themes of the ever-presence of entropy, the ways it captures the gulf between the instant, crystalline conception of thought and the slow plunging of time in which a life is actually lived. In the narrative strand that takes place from Woolf’s perspective, we see her struggling efforts to begin writing the novel that becomes Mrs. Dalloway, to land the images she sees in her head, while fighting the re-encroachment of her own mental illness. Laura Brown, the LA housewife, deliberates on the baking of a birthday cake, destroys her efforts as insufficient, then later re-creates it, more perfect this time.

Clarissa, Richard, and Louis, the original triad of friends who hark back to their college summer in Wellfleet, their recollections in light-touched flashes, now move through their days from moment to creeping moment. Illness and time are the combined weights that bear down upon each of them.

It is the kingdom of illness, mental and physical, and how it stretches on and on, that the novel exposes so viscerally. And this was the world where, suddenly, my husband and I came to live as he sought to come to terms with his new, broken body and I had to learn the most unpleasant and intimate ways of caring for him. I can’t think of a novel that better documents both the physical minutiae and the boredom of what these hours involve. I’m amazed at just how apt is the following description of the chair where dying Richard daily sits:

Richard’s chair, particularly, is insane; or, rather, it is the chair of someone who, if not actually insane, has let things slide so far, has gone such a long way toward the exhausted relinquishment of ordinary caretaking—simple hygiene, regular nourishment—that the difference between insanity and hopelessness is difficult to pinpoint. . . . The chair smells fetid and deeply damp, unclean; it smells of irreversible rot. If it were hauled out into the street (when it is hauled out into the street), no one would pick it up. Richard will not hear of its being replaced.

The great shock, for me, of reading this book in 2023 was how vividly it brought back memories of the AIDS crisis. I was (and am) a fairly traditional Christian, but I was never sheltered, and my 20s were full of nightclubs and urban neighborhoods and friends-not-like-me where the illness’s reach was haunting and unmistakable.

The landscape of the crisis seems now to have vanished from the public imagination. That is both a blessing and a miracle, of course—though the disease persists mightily in places like Washington, DC, and my native Mississippi. But even as it has become a ghost, an afterimage in history, I’m struck once again by how those recollections of the AIDS crisis now read to me as deeply Christian. And not just in plodding, workaday terms of caretaking or mercy or even that now-freighted goal of social justice. What strikes me now is not ideology but simply the imagery—the hands offering so much love amid so much suffering.

Death and life are closely, essentially twinned—both ultimately and within the heart of each hour.

While The Hours is a book that in theory has no explicit Christian aspirations whatsoever, it is hard not to read its inextricable intertwining of the physical and the spiritual as essentially Christian, because incarnational.

What is Christlike about Clarissa is her ability to recognize the enduring human (and thus, the divine) within the decay and her continued accompaniment of Richard: “Clarissa, Richard’s oldest friend, his first reader—Clarissa who sees him every day, when even some of his more recent friends have come to imagine he’s already died.”

The suffering here is transformative, even when it can feel meaningless. Death and life are closely, essentially twinned, the book reminds us. This is true both ultimately and also within the heart of every one of those hours, as we ourselves experience them along with Clarissa, Richard, Laura, and Virginia. From hour to hour, from moment to moment. The book’s shimmering idea is also embedded in its substratum.

In a novel replete with incarnational moments, I keep coming back to that establishing image of Clarissa on the streets of New York with her sheaf of flowers. When I first came to love it, I saw the floral spray as gift and tribute, her desire to honor Richard. Then when I reread the book as my husband hovered between life and death, I at last saw the funerary imagery embedded in the offering. For Richard is, in fact, dying, and in the course of the novel he dies on the page.

I am now living many deaths—my marriage as I knew it, but also my husband’s personality, even if its outlines and essence remain. And I am mourning my own expectations amid all the caretaking and worry, missing my own shimmering days with him on the dunes at Wellfleet. (For us it was Martha’s Vineyard.)

But there are still the flowers! And this is where I will draw on a somewhat more explicit Christianity: I will be Clarissa and continue to bear my flowers forward. For flowers are not solely heralds of death. We also place them at altars, and I am living at one now. We Orthodox also leave them at the altar sometimes—after the Paschal passage, it takes some time to live into the resurrection, and I have seen those altar flowers linger until long after their dewy bloom is gone and their heady fragrance is a touch past sweetness.

For most of us, in fact, we begin at the resurrection, and once again we wait—until that moment of Pentecost when the Spirit that gives life is more generally shed upon us all.

Like my husband, like Richard, I too am waiting.