Cecil Williams kept his ear to the ground

The longtime pastor of Glide Memorial Church was involved in nearly every major social justice movement in the Bay Area for 60 years.

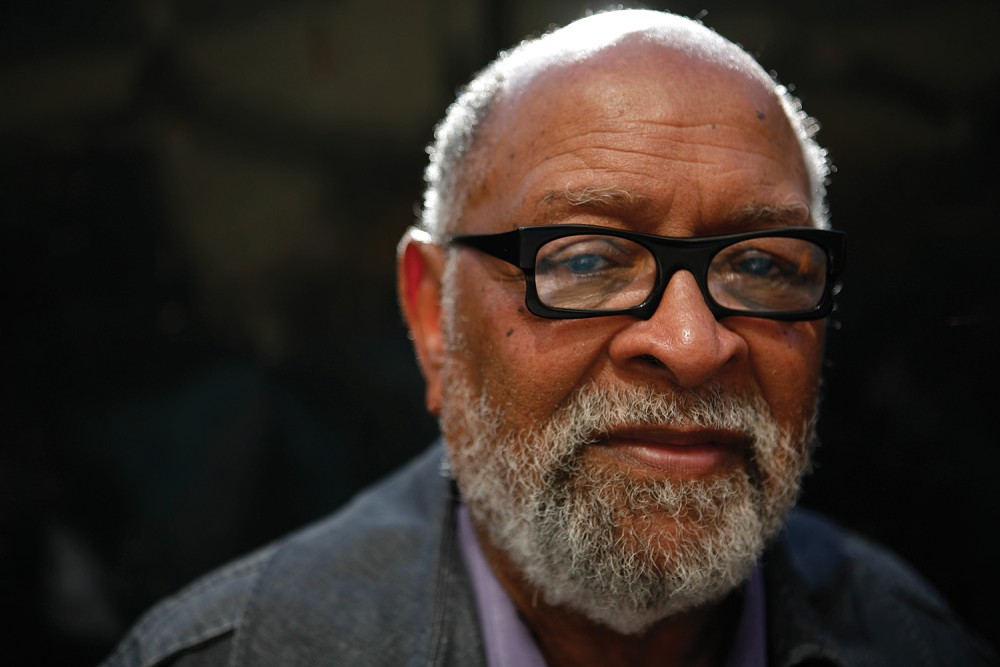

Pastor and activist Cecil Williams (San Francisco Chronicle / Hearst Newspapers via Getty Images)

In the movie The Pursuit of Happyness, which is based on a true story, Will Smith portrays Chris Gardner—an unhoused, Black, single father in San Francisco. In one scene, he and his young son go to Glide Memorial Church, where they’ve been told they can get a hot meal and secure a bed for the night. While they are waiting in line, the pastor comes outside to announce that there are only a few beds left. Gardner and his son will get the last one. Those familiar with San Francisco may recognize the pastor in these scenes as Cecil Williams, Glide’s real-life longtime pastor.

Williams, who served in various pastoral roles at Glide for nearly six decades, died this April. He spent many of those years regularly greeting folks in line for Glide’s free hot meals, and he leaves behind an enormous legacy of ministry and activism in San Francisco—one that inspires leaders today to work for liberation and to reimagine what the church can be.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

I first met Williams in 2017 through Glide’s Emerging Leaders Internship program for college students, where I worked on a history project to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the Summer of Love in San Francisco and at Glide. My project led me to the Glide archives and gave me the chance to interview Williams and his wife, Janice Mirikitani, the former Glide Foundation executive director who died in 2021. As the summer wore on, I became obsessed with chronicling Williams’s legacy: he had been a massively important figure in the religious landscape of San Francisco, and yet most people in my generation didn’t know who he was.

Seven years later, Williams is gone and I am a young clergyperson in San Francisco, desperate for hopeful examples of what ministry can be at its best. In Williams, I see someone who revived and transformed what had been a dying church—something many pastors of my generation will be tasked with at some point. Though he was surrounded by tremendous pain and suffering in the Tenderloin neighborhood, he cast a vision for a liberated world that drew crowds of people in and demonstrated that the church could be a real ally in combating dehumanizing forces of oppression.

Williams was raised in segregated San Angelo, Texas. His maternal grandfather, Papa Jack, had been enslaved and migrated to the Southwest once freed. Toward the end of his life, Papa Jack sat all his grandchildren down and said to them, “Papa’s an ex-slave. Now you all be ex-slaves, too.” In that lesson, Papa Jack planted the seed for young Williams to begin to understand liberation, which eventually became the guiding force of his life and ministry. He felt called to the ministry from childhood and eventually became one of five black seminarians who together integrated Southern Methodist University. After a few other pastoral appointments, Williams arrived at what was then called Glide Memorial Methodist Church in 1964.

When he first visited the previous year, he found a church that was financially stable—buoyed by the cattle fortune of the Glide family—but mostly empty. There were 35 White people “intent on keeping services conservative and starchy,” as Williams wrote in Beyond the Possible. All that quickly began to change when he took over as the pastor. He began preaching a message of inclusion and welcome to all people, inspired by nuns and priests in South America who described a vision of the kingdom of God that would later be called liberation theology. He changed the music from traditional hymnody to a rousing gospel choir. He welcomed those in the Tenderloin who had been implicitly or explicitly denied entry.

Throughout his 60 years at Glide, Williams was involved in nearly every major social justice movement in the Bay Area. Huey Newton called him from the hospital after he was shot by the Oakland police in 1968. In 1974, Williams offered city sex workers space to host a “Hookers Convention” to advocate for decriminalization. In 1982, he was arrested while protesting the development of nuclear weapons at the Lawrence Livermore Laboratory in Berkeley. During the 1990s, he was called on to consult with multiple presidents and Congress on the crack cocaine epidemic. The list goes on.

Williams often said that the most important thing in social justice and liberation work is that you walk the walk—that people don’t just study society’s problems and talk about how important it is to fix them but follow through and do the work. “Put your body where your mouth is,” he would say.

Williams’s ministry was guided by the action-reflection cycle of liberation theology. He read and was influenced by Leonardo and Clodovis Boff, who describe liberation theology as operative “within the great dialectic of theory (faith) and practice (love)”: it must always consist of both action and reflection. For Williams, this meant acting—at Glide and in the community—in support of the poor and oppressed, along with writing and preaching about liberation.

The marginalia and highlighting in Williams’s personal copy of the Boffs’ Introducing Liberation Theology offer a glimpse into the way he understood himself as a theologian of liberation. The Boffs focus on three categories of liberation theologians: popular, pastoral, and professional. Williams’s work falls under the pastoral category, a middle ground between the professional and the popular, in which the work is grounded in a concrete community and is always related to practice yet also utilizes preaching to cast a vision of God’s preferential option for the poor.

In 1969, just as liberation theology was gaining popularity, Williams scandalized fellow Christians by removing the cross from the Glide worship space. While some liberation theologians understood the crucifixion as an act of solidarity with suffering and oppressed people, Williams saw it differently. He strongly condemned the church’s use of the cross as a “gentle” symbol. In 1971, after a newspaper reporter critically noted that Glide was “missing” a cross, he preached a sermon titled “Bring Your Own Cross,” in which he explained his intentions.

“If the cross says anything, it means that it’s in the midst of the people,” Williams proclaimed. Along with being a symbol of violence, Williams saw how a cross hanging in a church symbolically confined Jesus to that space.

“Did he stay in the synagogue?” Williams asked. “No, he went among the people and touched them and fought with them and . . . emoted with them, talked to them, worked with them, protested with them, led them in demonstrations. What a great revolutionary!” Williams called on the people of Glide to be active in the world and to join the marginalized in the fight for liberation:

Get out there where people are and change with people. . . . Let the world know that we believe in justice and mercy and liberation. Let the world know that we the people, as we come together, will not have dehumanizing forces impinge upon us without fighting them. And so, I say to you the liberators, you the messengers, bring your crosses and let them be lifted and move on in liberation for all the people. Move on!

Williams’s legacy lies in both the content of his liberation work and his strategy for getting there.

First, the strategy. After the majority of the existing 35 Glide members left upon Williams’s arrival, he turned to novel strategies to bring people in. He welcomed in the marginal people of the Tenderloin, including sex workers, drag queens, young runaways, hippies, Black radicals, drug users, survivors of police and domestic violence, and so many others. He included them in worship, but he also gave them office space and partnered with them in their own community-based efforts at liberation. This ragtag community, to Williams, reflected the kingdom of God.

I see this approach as an inspiring example. Countless churches today sit nearly empty, as Glide did in 1963. Williams’s strategy of flinging the doors open to mission-driven groups that serve the local community is essential. Not only did this bring people back into the pews, but it also brought vibrancy and immediacy to the community. For urban churches that have the gift of space, Williams’s legacy might inspire us to leverage our spaces for mission, trusting that this act of faith is also an act of evangelism.

Over time, under Williams’s leadership, Glide used its space to develop more of its own programs, which continued to reflect the needs of the neighborhood. The church began its first iteration of the now famous meals program during the Summer of Love. During the AIDS epidemic it began offering free HIV and STI testing, and during the crack cocaine crisis it responded by starting recovery groups and support groups for those still in active addiction, as well as by hosting conferences to call people of faith to action. The church eventually opened a childcare and family support center and invested in affordable, supportive housing. Finally, toward the end of Williams’s tenure, Glide began offering harm reduction services, which have grown massively since then to address the current opioid overdose epidemic.

Technically most of these services are provided by the Glide Foundation, which is separate from Glide Memorial Church. But the work of the church and the foundation are intertwined: people came to worship at the church because they connected with the work the foundation was doing in the community. The church became the spiritual beating heart of a much larger movement toward liberation for the marginalized of the Tenderloin and of San Francisco more broadly.

Second, the content of Williams’s work. It inspires me to reimagine what the fruits of liberation might look like today. Williams advocated for many marginalized groups that continue to need our support: migrant workers, Indigenous activists, mutual aid networks, impoverished children and families. There was not an issue that Williams was not willing to look in the face and tell the truth of the gospel. But most notable for ministers today are the people Williams included, the ones who earned him the title of “controversial preacher of the streets.” Williams brought in folks who were ostracized by the rest of society and whom many people outright feared—especially sex workers, drug users, and people with HIV and AIDS.

As young clergy like me seek to revitalize churches, we might imagine that healthy, housed, sober people will fill up our pews. We might imagine that the church will help drug users and sex workers and the unhoused, but not that they will be a part of our congregations. Williams’s message was exactly the opposite. He constantly preached that everyone is in need of liberation from something and that nobody can save anyone else. Instead, he offered a vision of a community of people who respond to the Spirit together and seek liberation side by side.

“To be set free is to be set free to give life,” Williams said from the pulpit in 1985. “We’re set free to give life, to give love. My God, isn’t it something to give love!” Seeking liberation was, for Williams, the great equalizer. It is the task at which God sets us, and the result is that we exude love.

Williams explained that he was able to do what he did because he always kept an “ear to the ground,” listening to folks around him and hearing God at work among the poor, gender and sexual minorities, and the racially diverse tapestry of neighbors that made up the Tenderloin. His legacy is a reminder to Christians today to not lose hope in the face of church decline. God’s vision for a liberated world has the power to transform any community, if only we are willing to keep our ears to the ground.