Can we save democracy in the United States?

I grew up in Taiwan and Argentina. Here’s what I know about authoritarianism.

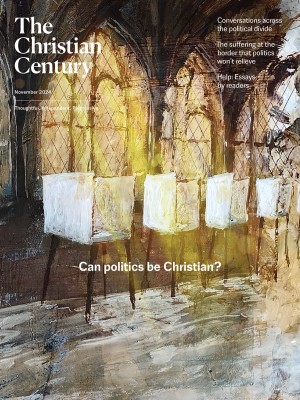

(Century illustration)

Editor's note: A Spanish translation of this article is available here.

My father was born in a Japanese colony that ceased to exist by his fourth birthday. My mother was born on an island that was surrendered to a neighboring authoritarian state by its colonizers. I was born in a country under martial law. All of us were born in Taiwan.

We are embodied survivors of authoritarianism. We know what it’s like to live under totalitarian rule. We remember the fear of saying what you really believe. We know what it’s like to be paranoid that our neighbors might snitch on us. We have seen how a mistake could destroy our reputations or our lives. We know what it felt like to live in a homeland that didn’t feel like home. So we became Americans: we are Americans today because of what happened in our homeland.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Many of my fellow Americans claim that the United States feels more and more like the nations we left behind. They are scared to say the wrong things; they don’t know who to trust; they feel like their government is against them. Some even think the US has entered an age of authoritarianism. We—immigrants, refugees—know that it has not. We also know we cannot allow it to.

Portuguese sailors in the 1500s called Taiwan “Ilha Formosa,” “beautiful island.” In the 1600s, it was a colonial trading outpost for the Spanish and Dutch. According to family lore, my uncles’ pointy noses and curly hair may be the genetic legacy of the Dutch. In 1895, Japan colonized the island as part of its conquest throughout Asia, which reached as far west as Burma and as far south as the Solomon Islands. My grandparents and some of my uncles were fluent in Japanese. In the only surviving picture I’ve seen of the grandmother I never met, she is wearing a Japanese kimono.

My mother was born just after World War II, when Japan surrendered the island to the Republic of China. Some Taiwanese citizens claim it was surrendered to the wrong country. Fifty years earlier—just before Japan took over the island—Taiwan had declared independence, naming itself the Republic of Formosa. For the five months this republic existed, it went unrecognized by other nations. Still, this was a step toward independence. China, of course, claims it recovered Taiwan, a recovery not of its own merit.

The Republic of China, under the rule of Chiang Kai-Shek’s Kuomintang (KMT), took the island from the Japanese and reigned with brutal force. In 1949, the KMT was defeated by Mao Zedong’s Chinese Communist Party and fled to Taiwan, declaring it the official Republic of China. The KMT would rule Taiwan with the full might of a right-wing authoritarian military force. I was born in the era known as the White Terror, 40 years of martial law filled with political assassinations, murders, and kidnappings. Thousands of Taiwanese citizens were killed—between 18,000 and 28,000 in the February 28, 1947, massacre alone. An additional 140,000 were arrested and tortured. That meant every Taiwanese citizen, including my family, knew or was related to a victim or a perpetrator.

My mother’s father was one of the few native Taiwanese sent to receive graduate education in Japan during colonial times. He was considered an elite before that label was associated with wealth. He returned to Taiwan to be the dean of a seminary and the pastor of a local church.

On the morning of January 6, 1960, he dropped my mother off at school on his bicycle and continued on toward a pastoral visit. A vehicle struck and killed him before he got there. The death was recorded as an accident. The driver was a government official: the vehicle was part of President Kai-Shek’s fleet of cars.

My mother was only 14 years old. She remembers the driver coming to their house with a stack of cash, asking my grandmother to drop the charges against him. The amount was equivalent to three months’ wages. Though they desperately needed the money, my grandmother refused.

Why would the government want to kill a beloved pastor? Under martial law, asking questions only leads to more accidents. The family forced itself to accept the official account.

Decades later, under the safety of distance and the freedoms of the United States, my grandfather’s friends told my mother what many suspected: it was no accident. KMT officials monitored their Presbyterian church weekly. They came two at a time, always carrying trench coats. They sat through worship and never spoke to anyone. Church gatherings were monitored throughout the island. Those were the norms under the White Terror. My grandfather was targeted not for what he said but for his leadership. Moral leaders are a threat to authoritarians.

My grandfather’s friends encouraged my mother and her siblings to demand an investigation, but the trauma of the past prevented them from trying. Their generation waits for wounds to scar over, even if they never do. During reigns of terror, only God knows the truth. For many that is enough.

I was born 14 years after my mother lost her father. She named me after him. I am one of the many living legacies of the White Terror, a story I know only through a language I barely understand. Still, like every person of Taiwanese descent, my existence is defined by the horrors our ancestors lived through.

My family was one of the few fortunate ones to escape to another country—one also ruled by the fear of political assassinations and kidnappings. We traded the White Terror of Taiwan for the Dirty War in Argentina. Between 1974 and 1983, Argentina was ruled by a right-wing military junta supported by Henry Kissinger’s Operation Condor, a campaign of political repression that sought to wipe out left-wing sympathizers throughout South America. In Argentina, thousands of citizens disappeared, the true number lost in the ocean, where the bodies were thrown.

My uncle instructed us never to run in the streets. Keep your eyes down. Fear the police. Fear the secret police even more. I was a child; I didn’t understand what my first-grade classmate meant when he came to school crying, saying his brother was “taken” overnight. I thought Señorita Marta’s teenage son came to our second-grade classroom because he liked us, not because he was hiding.

I did not know until the military dictatorship collapsed and democracy was restored in 1983. There was joy in the streets. Everything changed. A shroud was lifted. People talked freely on the streets, in the stores, and in the parks. I was only a kid, but I felt the jubilation as people voted in that first election.

But democracies are unruly. Argentina suffered its first of many financial crises in 1989. My parents owned a small grocery store, and hyperinflation made it impossible to stay open. We were among the many families who left that year.

We emigrated again. This time by choice, not by force, to the oldest democracy, where my family found safety, prosperity, and peace. But as the United States nears its 250th year of existence, I recognize that the homeland we escaped all those years ago is now more free and equal than the one I escaped to.

Some people think the US has entered an age of authoritarianism. We immigrants and refugees know that it has not—and that we cannot allow it to.

In the most recent Democracy Index published by the Economist Group, Taiwan is categorized as a full democracy, while the United States is “flawed.” Even with a parliament that often resorts to physical fights, Taiwan is among the ten strongest democracies in the world, and it’s number one in Asia. The US ranks as the 29th most democratic nation in the world. Compared to the US, Taiwan has better health care, lower cost of living, less crime, and more human and personal freedoms. Some might read this and say, “Why don’t you go back where you come from? If Taiwan is so great, leave.” Some Taiwanese Americans have already done so. But the future of Taiwan is intertwined with the next US election.

Since its enactment by Congress in 1980, the Taiwan Relations Act has stabilized tensions between China and Taiwan. The act commits the United States to provide weapons for Taiwan to defend itself, without committing to direct US involvement. Since its inception, every US president has upheld the agreement. The navy has sent warships to the region when China has fired missiles into Taiwanese waters—as it did again this January, after the most recent election in Taiwan. China has antagonized neighboring countries and expanded its reach into the South China Sea, putting the Philippines on high alert.

If the United States elects a president who will not stand by its allies or honor its treaties, China will likely move in on Taiwan. This is not a threat to Taiwan alone. Authoritarian leaders around the world will pounce on the countries they’ve been longing to overtake. Freedom and independence in the countries many US immigrants come from are under threat. If we give up on our current country, it means the demise of the countries of our pasts.

The United States is far from perfect and is capable of much wrong. I’ve lived through the devastation of US foreign policy; many immigrants are here because of what the US did to our home countries. Many of our ancestors fought to win rights that the US founders did not believe were endowed to us by our Creator. We should not dishonor them by claiming our times are worse than theirs; they are not. We left our homelands because our hope was in a different land. Now we must keep that hope alive.

Immigrants and refugees have special gifts to give this country. We also have a special responsibility in the face of looming authoritarianism. We know what it’s like to live in countries that will not protect our existence. We escaped because there was nothing we could do and so much they could do to us. Yet even under those conditions we fought to make things better. Now we have freedom, rights, protection, and influence; we have a voice and a vote. We have to use them while we can.