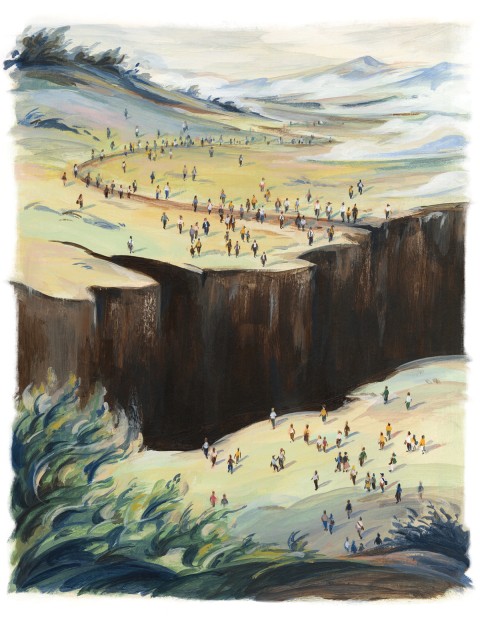

Bridging the ideological divide

It isn’t easy to lower the temperature of our political discourse. But there are people working to help us have better conversations.

(Illustration by Sally Deng)

Last fall, I heard an unforgettable talk by Dan Leger, a survivor of the 2018 mass shooting at the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh. He spoke of the ways he has sought to maintain his faith in God and humanity since that horrific day when 11 of his fellow congregants lost their lives—and he nearly lost his own. He has drawn strength from devoting his life to two things: lobbying for gun control and urging Americans to become less polarized in our political and civil discourse. “We need to have better conversations,” he said.

Many of us have seen the unfortunate effects of polarization and political discord within our churches, both at the wider institutional level and within individual congregations. Like others, I can also relate to these challenges personally. As an only child of two octogenarian parents whose political views are firmly opposed to mine—parents whom I love deeply and whose care is my responsibility—I must contend with divisive, challenging conversations constantly. The same holds true in my workplace, a Benedictine Catholic liberal arts college where I encounter ideological diversity in the classroom every day.

Lowering the temperature of our discourse is not easy. Over the past several years, however, I have encountered people in both the religious and secular realms who are working to encourage us to have better conversations.