When the doctrine of discovery became law

Steven Schwartzberg shows how the 19th-century arguments for Native American expulsion went against the intentions of the framers of the Constitution—and how they remain with us today.

Arguments over Genocide

The War of Words in the Congress and the Supreme Court over Cherokee Removal

“I was the witness of sufferings which I have not the power to portray,” wrote Alexis de Tocqueville in Democracy in America after seeing Choctaw nationals cross the Mississippi River into Arkansas on their way to the Indian Territory, now Oklahoma. The US government’s expulsion of Native American tribes from Georgia, Alabama, and Mississippi in the 1830s is among our gravest—and often misunderstood—national sins.

To be sure, generations of middle and high school students have learned about Andrew Jackson, the Indian Removal Act, and the Trail of Tears, including some sense of its brutality and death. However, these lessons frequently come from perspectives that focus on national expansion and manifest destiny, rather than on the experiences of Native Americans or even the legal and ethical obligations of the US government. For example, the state of Texas’s social studies standards merely require students to be able to “analyze the reasons for the removal and resettlement of Cherokee Indians during the Jacksonian era.”

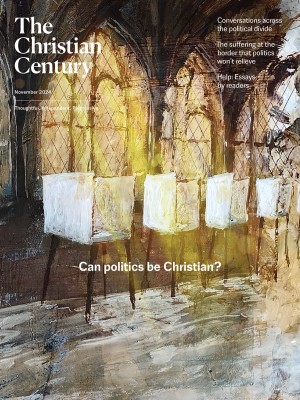

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Steven J. Schwartzberg steps into this dearth of understanding to examine how the reasons given for Native American expulsion were extensions of the doctrine of discovery drawn up in legalese. More vitally, he shows that these arguments, crafted in the 1820s and 1830s contrary to the intentions of the framers of the United States Constitution, are still with us and must be overcome before there can be a true reconciliation between our government and Native American nations.

Schwartzberg, an instructor in political science at DePaul University, writes on the intersection of law, theology, and public policy. He does not shy away from classifying the federal government’s past actions as genocidal under contemporary international law. But his greater contribution is in tracing, sometimes in painstaking detail, how the arguments and debates in Congress and the Supreme Court during the 1820s and 1830s broke from an earlier tradition—exemplified in Schwartzberg’s account by James Wilson, a Pennsylvania delegate to the Constitutional Convention and one of only six men to sign both the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence—of understanding the United States government’s treaties with Native American nations as binding promises.

To understand Schwartzberg’s argument, a little constitutional history is in order. Article VI, clause 2 of the Constitution states that federal laws and treaties made under the Constitution’s authority “shall be the supreme Law of the Land.” This clause, Wilson argued, “will show the world that we make the faith of treaties a constitutional part of the character of the United States.” In the decades after the Constitution’s adoption, the federal government negotiated, and the Senate ratified, hundreds of treaties with Native American tribes using the same process as treaties with European nations.

That approach changed as the young nation continued to expand. When the United States Supreme Court decided Johnson v. McIntosh (1823), it set the groundwork for forced expulsion by introducing the doctrine of discovery into federal law. In Johnson, Chief Justice John Marshall wrote on behalf of the Supreme Court that the “absolute ultimate title” to land in the United States “has been considered as acquired by discovery, subject only to the Indian title of occupancy, which title the discoverers possessed the exclusive right of acquiring.” Marshall also added that this right to occupancy could be acquired “either by purchase or by conquest.” Might literally makes right.

In the subsequent cases Cherokee Nation v. Georgia (1831) and Worcester v. Georgia (1832), the Supreme Court held that the federal government, not any one state, was to be the purchaser or conqueror of lands occupied by Native American tribes. By that time, Congress, at President Jackson’s urging, had adopted the Indian Removal Act to compel tribes to subject themselves to state laws or be expelled to the Indian Territory. This forced concession of tribal sovereignty could only happen with the legal structure that Marshall crafted and which still exists, albeit in a modified form, today. As recently as 2005, Supreme Court justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg cited the doctrine of discovery in City of Sherrill v. Oneida Indian Nation of New York, which held that lands reacquired by Native American tribes in the open market could not benefit from the same property tax exemptions as lands that had remained in tribal hands in perpetuity.

While Schwartzberg’s book is important, it assumes knowledge and facility with a historical narrative that too many people lack. Narrative histories like Claudio Saunt’s Unworthy Republic seem better suited for readers to develop a general understanding of Native American expulsion, though Saunt’s account lacks both Schwartzberg’s close readings of the policy’s foundational cases and debates and his legal and ethical analysis of those texts. Nonetheless, Schwartzberg would have been better served by a heavier editorial hand, in particular to reduce the number of block quotations of florid 19th-

century prose while maintaining or even strengthening the rhetorical import of the remaining quotations.

In the end, Schwartzberg’s argument is an important one for our country to grapple with. Schwartzberg refers to movements, such as Land Back, that aim to repatriate Native American tribes on their historic lands. He also suggests several theological resources, including Terry Wildman’s First Nations Version of the New Testament (reviewed in the May 18, 2022, issue), to understand the critique of power at the heart of Christianity that the doctrine of discovery perverted. Nonetheless, because we continue to live in the systems we live in, I also would have liked it if he had explored how the US government and, in particular, White Americans can engage in collective action to make reparations for these national sins.