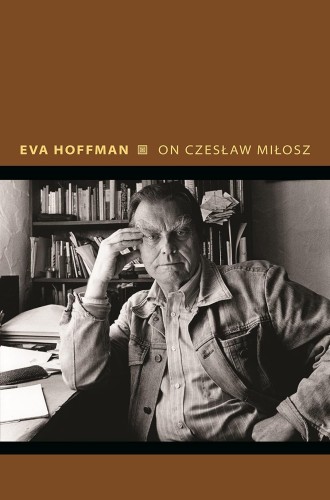

Understanding Czesław Miłosz

Eva Hoffman, a fellow exile from Poland, writes about the Nobel-winning author like no one else could.

On Czesław Miłosz

Visions from the Other Europe

This illuminating study by novelist, historian, and critic Eva Hoffman is a literary biography of the Polish Nobel laureate Czesław Miłosz. One of the greatest writers of our time, Miłosz captures in much of his writing the intensities of a violent century of war and the terrors of authoritarian regimes. A Catholic who helped to shelter Jews, he writes about the Holocaust, but he also writes about the loneliness and longing of exile, reaching back into memory of the particulars of his early life. “It is possible,” he mused in his 1980 Nobel lecture, “that there is no other memory than the memory of wounds.”

Hoffman, who grew up in Kraków, knows well the life of exile. She emigrated to Canada and now teaches in London. This biography of Miłosz contains many of her own personal reminiscences. She knew Miłosz as only another Polish writer could know him, as she has known other Polish Nobel laureates. That makes this book, written from a fresh new angle, both distinctive and trustworthy. She summarizes Miłosz’s complexities this way: “From an obscure Lithuanian hamlet to San Francisco Bay, from historical past to the hypertechnological future, from the Bible to pop culture—Miłosz’s range was enormous, and his need to grasp it all came close to a kind of torment.”

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Hoffman juxtaposes Miłosz’s experiences of the world into which he was born (the “other Europe” of the book’s subtitle) with his life at Berkeley and trips through Middle America, where he found both Bohemians and evangelicals and refused to choose between them. Hoffman cites his account of meeting with a “young simpleton” who asked “how life in Sacramento differed from life in a concentration camp.” Miłosz insisted that America was not a comfortable place for him, but he showed both admiration and compassion for Americans. Poland was “all past,” he observed, and America “all future,” which meant that, predictably, America lacked historical perspective.

In his essay “A Certain Illness Difficult to Name,” Miłosz identifies the plight of the immigrant and names it “ontological anemia,” caused by the vast spaces of America, unimaginable to those who emigrate from small towns in Eastern Europe. Hoffman explains how this disease results from the sense of unlimited space combined with the “frontier individualism” imbuing the American ethos. As an immigrant, Hoffman identifies with the alienation she finds in much of Miłosz’s writing. In fact, her asides, in which she recounts her experiences, give this study the depth afforded by the similar angles of vision in writer and subject. At one point she insists that “the sharpest angle of vision is often oblique.”

While Miłosz wrote in many genres—essays, fiction, memoir—he is best known for his poetry. Hoffman quotes a few lines from his book-length poem, A Treatise on Poetry:

Novels and essays serve but will not last.

One clear stanza can take more weight

Than a whole wagon of elaborate prose.

She notes that his two best-known poems, “Campo del Fiori” and “A Poor Christian Looks at the Ghetto,” were quite possibly the earliest meditations on the Holocaust by one who did not have direct experience of the camps or the Warsaw Ghetto. The memory of extermination, he insists in the latter, will be present even in “the ashes of each man.”

I was present when Miłosz received a lifetime achievement award from the Conference on Christianity and Literature at the 1998 Modern Language Association annual meeting. The organization was aware that its little award could not compare to the other awards he had received, but he was deeply appreciative. Being recognized as a significant voice in the world of Christianity and literature, he said, meant more to him than any other award he had received.

In many of Miłosz’s poems in the last years of his life, Hoffman writes, he expressed a strong desire for faith. She cites a poem he wrote after the untimely death of his second wife, Carol Thigpen, in which he steps into the shoes of Orpheus mourning Eurydice’s death:

Under his faith a doubt sprang up

And entwined him like cold bindweed.

Unable to weep, he wept at the loss

Of the human hope for the resurrection of the dead.

Because he was, now, like every other mortal.

His lyre was silent, yet he dreamed, defenseless.

He knew he must have faith and he could not have faith.

Miłosz eventually moved back to Kraków, where he lived until his death in 2004. Hoffman quotes his poem “And Yet the Books” to show that Miłosz realized he would indeed find life after death through the work he left behind:

I imagine the earth when I am no more:

Nothing happens, no loss, it’s still a strange pageant,

Women’s dresses, dewy lilacs, a song in the valley.

Yet the books will be there on the shelves, well born,

Derived from people, but also from radiance, heights.

Only Eva Hoffman could have written this biography, a rare thing springing from Hoffman’s and Miłosz’s similar lived experiences of exile and suffering, revealing a shared understanding of what freedom from tyranny means while anchored in the tentative position of the immigrant.