The puzzle at the heart of Mormonism

Historian Richard Lyman Bushman investigates his own tradition’s most mysterious miracle.

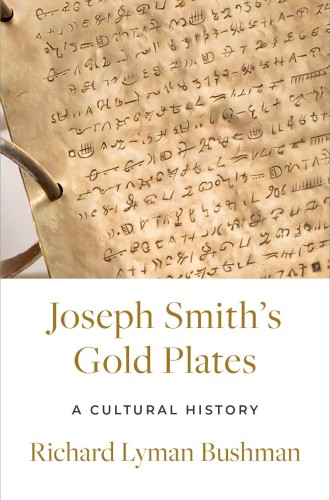

Joseph Smith’s Gold Plates

A Cultural History

Most creation stories are shrouded in mists of ambiguity and sometimes bitter controversy. Not this one. With remarkable unanimity, members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints trace their origin to a cluster of supernatural events that took place in the 1820s in or near Palmyra, New York. Today, just two centuries later, they claim 7 million followers in the United States and Canada, another 10 million around the world, and 100,000 short- and long-term missionaries everywhere.

Figuring out how and why this movement, once fiercely countercultural, grew so fast and spread so widely invites multiple explanations. But one of them is believers’ unwavering conviction that divine interventions manifested themselves right from the start. Richard Lyman Bushman, a Latter-day Saint and professor emeritus of history at Columbia University, tells this story with both the warm heart of an insider and the cool eye of an outsider. Putting the two perspectives together, as he does, is a remarkable feat, brilliantly executed.

Insiders’ creation narrative runs like this: in the spring of 1820, in the “First Vision,” God the Father and Jesus Christ the Son informed 14-year-old Joseph Smith Jr. that all existing sects were wrong. He should join none and await further instructions. Those came soon enough.