The Obama campaign, fictionalized

Vinson Cunningham’s debut novel focuses on a campaign staffer’s indeterminate views, using them to shed light on the rise of a political star.

Great Expectations

A Novel

To paraphrase an online saying: you’re not nostalgic for Obama’s first campaign, you’re nostalgic for the age you were during Obama’s first campaign. From the very beginning, it was disorienting to watch his sudden rise from unknown to inevitable. With hindsight, it can seem as though he was uniquely positioned to claim the central, near universalizing place in American politics for almost a decade: the son of one Black and one White parent, one native-born and the other an immigrant; an adoptive son of the Midwest, the crucial confluence of New England Puritanism, the Great Migration, and pan-European immigration and the onetime stronghold of small farming, unionized industry, and land grant universities; Protestant, but of a rhetorical rather than a confessional flavor; someone who walked the halls of elite institutions but only as a newcomer. He could not merely code-switch; he could speak in different registers to different people using the same words. He made space for belief, although in what and for whom were always left open to interpretation.

When he ran for US Senate in Illinois in 2004, I was worried that his name and his liberal profile would make him hard to elect. He won 70 percent of the vote. Still, it all looked like a roll of the dice as his national profile rose during the second Bush term. For many people, it was the first time they engaged in politics. For progressives who came of age during the Bush years, it was the first time they engaged in politics out of anything other than fear, anger, or hostility. For many, young and old, it was probably the last.

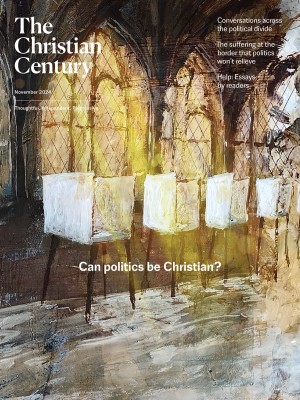

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Vinson Cunningham’s debut novel Great Expectations, a bildungsroman-cum-campaign memoir, begins at the very moment Obama launches his presidential campaign. The narrator, David Hammond, sees him on television making his announcement in Springfield with a rhetorical flourish straight out of the Black church tradition: “Giving all praise and honor to God for bringing us together here today.” David is, and remains, something of an ironist throughout the action of the book (at least where politics are concerned), but he feels “almost flattered” to be pandered to in this way by a politician who wants something from him. It makes him feel “bright, disconnected, and experimental.” He imagines Obama’s speech as the “melody” developed from the original theme of John Winthrop, who, speaking to the Puritan arrivals, became a “paganizer” and secularizer of Christianity by making it literally political.

Hammond—a name he shares, as he eventually points out, with the electric organ that is virtually synonymous with Black church music in the middle of the last century—wanders onto the staff of the nascent campaign’s New York fundraising office through a connection from a tutoring gig. He has recently fathered a child he parents part-time, he has dropped out of college, and he seems to be sojourning on the unstable frontier of his religious identity. But while he evinces no passion for the work and no particular eye for its details, he usually agrees with the people around him, complies with their requests, and keeps the donors happy.

Obama himself (usually typified simply as “the candidate”) turns up in person only a few times. David clocks his affect, his moods, his careful modulation of speech and physical bearing. He has an ear for verbal tics and what they say or avoid saying. (Obama uses the word look to “stud the pauses between his well-worn phrases.”) But the candidate mostly ends up serving as a mirror, or at most a catalyst, for the young staffers, middle-aged super-donors, and occasional celebrities and party hacks who flow through and around his campaign. David’s picaresque encounters with the campaign’s ancillary figures lead him into reminiscences and reflections on faith, music, education, and his family history. He’s the sort of person who, while everyone at the party is talking about current events or the campaign or anything else, will spend ten minutes looking at a piece of art on the host’s wall.

In his own obscure way, David shares his distant boss’s ability to serve as a canvas for the expectations of others. Henry Louis Gates Jr., in a funny early scene, is convinced he knows David. Peter Yarrow (of Peter, Paul, and Mary) gives him an unsolicited hug at a campaign event because David is the first person of color Yarrow has seen working on the campaign. He has, it is said in different ways, potential, and in the striving world of the Black bourgeoisie that proved so central to Obama’s early viability as a candidate, potential weighs heavily.

Through his genius for indeterminacy, Obama was able to defer the inevitability of disappointment.

The episodic structure and campaign setting of Great Expectations could have been exploited for a poison-pen satire of Obama-era liberalism. Or it could have skewered the upper-class Black milieu in which it begins and mostly remains. Cunningham, who worked on the Obama campaign and in the administration and now writes for the New Yorker, turns the story instead toward his narrator’s own preoccupations. The great benefit of being an ironist is that it keeps options open. Politics, money, art, parenthood, God: David spends most of the story having the wherewithal neither to foreclose nor settle upon any of them.

And this, we obliquely understand as the story builds toward election day and David’s return to Chicago and the church where his family once centered its life, is the great gift of the candidate as well. America did not know what it wanted or needed; or perhaps it needed and wanted too many things. Obama was able to defer the inevitability of disappointment through his genius for indeterminacy. He could flatter and admonish, burrow into the particular and escape into abstraction, in the same phrase. But only campaigning, as the saying goes, is poetry. Governing, like living, is prose. And usually not the fun kind.

Cunningham’s novel charms, digresses, penetrates, and startles, circling around a landing that often seems as though it isn’t going to happen. His narrator is erudite and conversational at the same time, equally eloquent on choral music and on the basketball play of late-career Paul Pierce. Like Saul Bellow’s Augie March (another reference that crops up in the novel’s expansive but lightly held manner), David is a serviceable American everyman with a library card, to whom things just seem to happen. Great Expectations doesn’t build any drama outside the narrator’s head—that’s one blessing and hindrance of using a frame from recent history—but it does, in a way, arrive somewhere. The make-believe world of the campaign has to end for the staffer no less than for the candidate.

As I finished Great Expectations, I found myself thinking back to Obama’s first inaugural address, in which he reached past his habitual references to Abraham Lincoln and the civil rights era to George Washington and the revolutionary generation. “We remain a young nation. But in the words of scripture, the time has come to set aside childish things.” I marvel—with the benefit of hindsight (as Cunningham’s narrator is fond of saying)—at the sternness of tone. Obama liked to tell us to grow up, and I don’t know if we or he ever believed it was possible. He’s used his post-presidency to collaborate with Bruce Springsteen and raise money for his presidential center, so perhaps he’s no better at taking his own exhortations than the rest of us. But if he, no less than Winthrop and Lincoln before him, ultimately failed to transcend the distinction between the City of God and the City of Man, the fault is with those of us who wanted to avoid the choice between the two. A politician, no matter how gifted, can’t make us grow up.