The humanity of human smugglers

Anthropologist Jason De León charts the desperation, grief, and friendships of the Central American guías who bring migrants across borders.

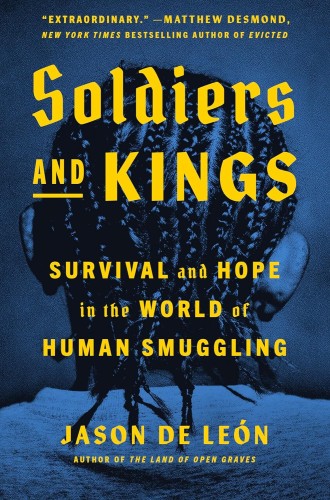

Soldiers and Kings

Survival and Hope in the World of Human Smuggling

Not every migrant is a criminal, I think to myself. This is my liberal conceit. My air of moral superiority. It is also my history. My grandparents are Mexican migrant farmers from the border of Texas and Mexico. My father migrated to the United States from the Philippines. When people accuse migrants of being criminals, I feel slighted and take aim with a well-worn defense.

But this conceit hides naïveté, shallow solidarity, a mistaken binary. I forget that appeals to “not every migrant is a criminal” can slight those migrants who, stuck between not wanting to return home and being unable to get to the United States, turn to the illicit work of smuggling to make a living. In an immersive and deeply personal work of ethnography and journalism, anthropologist Jason De León follows the lives and work of the Central American guías, smugglers who guide migrants across the wilderness and through the cities of Mexico to the southern border of the United States. What emerges is a haunting and humane portrait of those surviving amid harsh immigration policies that have exacerbated the precarity of migrant life.

In many ways, Soldiers and Kings can be seen as a sequel to De León’s The Land of Open Graves: Living and Dying on the Migrant Trail, in which he documented how US immigration policies such as prevention through deterrence weaponized the desert landscape of the southwest border to prevent people from migrating to the United States. Soldiers and Kings follows several guides in the aftermath of the Mexican enforcement project called Programa Frontera Sur, which was launched in 2014 to help immigration security forces apprehend and deport Central American migrants at Mexico’s southern border. The program’s deterrent policies, De León shows, force migrants to turn to guides who can find safe and secure routes to the United States.