Dress and redress

In a blend of memoir and scholarly inquiry, Megan Sweeney challenges readers to take clothing seriously.

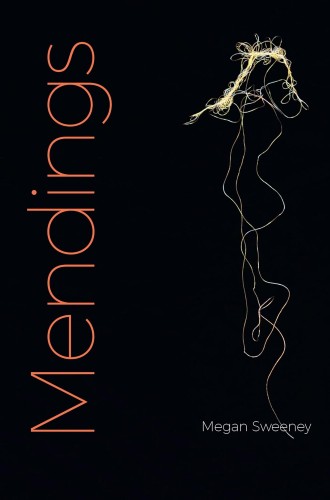

Mendings

Mendings opens on a familiar scene: tasked with cleaning house after the death of her parents, Megan Sweeney and her sisters sift through a lifetime of stuff. While her sisters are enthused to depart with familial excesses, Sweeney hesitates. She admits, “I need time to listen for the stories that objects tell, to dwell with my memories, to contemplate the pain next to equally powerful experiences of joy and bone-deep belonging.” Sweeney, professor of English at the University of Michigan, takes the stories among her familial debris seriously, and she approaches cloth and clothing as worthy objects of interpersonal exploration and reflection.

The result is a text bursting with stories of familial wear, tear, and repair writ large on keepsakes, or, as Sweeney calls them, “all-too-easily-discarded bits and pieces.” Across five chapters, Sweeney examines how her family’s stories reflect sartorial tasks, from salvaging to threading to mending. Throughout the book, Sweeney draws from prose and pictures to unravel the connections forged through textiles. Nearly every page intersperses personal anecdotes and theoretical reflection with pictures—of family photo collages, quilt squares, paintings, threads, and other relational fragments.

Word and image provide a sensorial feast for readers, who are invited to accompany Sweeney in her keepsake rummaging. In one chapter, she shares a paternal quilt, fashioned from garments and textiles rich with meaning to her father. Through text and textile, she displays how her “father is a quilt of many colors”—a parent who, like his own father, was alcoholic, withdrawn, and complicated through and through. In another chapter, Sweeney revisits childhood letters written to her mother, which make tangible the frays wrought through parent-child role reversal.