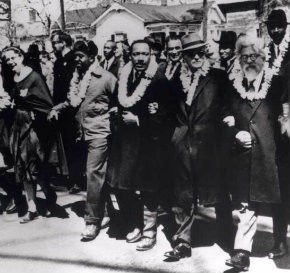

Remembering the march to Montgomery

In 1965, Martin Luther King Jr. sent a telegram to religious leaders asking them to come to Alabama to lend their support to the civil rights movement. It was the first time King had appealed directly to the conscience of the broader, mainly white, religious community. Describing the events of March 7, when dozens of black protesters were beat by white law enforcement officers, King wrote the following:

In the vicious maltreatment of defenseless citizens of Selma, where old women and young children were gassed and clubbed at random, we have witnessed an eruption of the disease of racism which seeks to destroy all America. No American is without responsibility....I call, therefore, on clergy of all faiths to join me in Selma for a ministers march to Montgomery.

The National Council of Churches issued an appeal of its own. Thousands of religious leaders and laypeople began to arrive in Selma to express their solidarity with the cause. John E. Hines, then the Episcopal presiding bishop, joined 500 other Episcopalians in making the trek—despite the objections of Alabama’s diocesan bishop, Charles C.J. Carpenter, who called the Selma protests “a foolish business and sad waste of time.” Carpenter urged his fellow Episcopalians to go home, but they did not.

Now, nearly a half century later, plans are taking shape in Montgomery to honor those who participated in what would become a historic five-day march from Selma to Montgomery—considered by many to be the most important such march in U.S. history, because it mobilized a nation and led to the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Current plans call for the new civil rights complex to be built on the grounds of the City of St. Jude, a Catholic-run social services center on the outskirts of Montgomery where thousands of marchers were allowed to camp on the final night of the march. It will include a 5,000-square-foot museum aimed at honoring the risks and sacrifices of the march participants.

Douglas Watson, executive director of the City of St. Jude, says that, along with the museum, a focal point of the $5 million complex will be an amphitheater built to represent the stage where many of the country’s best-known entertainers put on a spectacular show for the weary marchers on March 24. The “Stars for Freedom” rally—which featured Sammy Davis Jr., Tony Bennett, Leonard Bernstein, Mahalia Jackson and Peter, Paul and Mary—was organized and paid for in large part by Harry Belafonte.

“In all, that evening would cost me $10,000,” Belafonte, who was at the peak of his career as a singer and actor, later wrote. “I could handle that.”

Watson says that plans for the complex—which is being called the “Campsite 4 Experience”—are moving along “slowly but surely.” About $70,000 has been raised so far, plus another $25,000 in pledges. There may also be an opportunity to obtain some state, local and federal funding. “We are exploring all avenues,” says Watson, adding that they hope to sell 10,000 or more commemorative pavers to the public, representing the thousands of march participants and bringing in another $1 million or more.

According to Watson, plans call for breaking ground by March 2013—in time for completion by late 2014 and “most definitely” by the 50th anniversary of the march in 2015. “Expectations are high,” he says, “but so are the hurdles. Like everything else in life, it will take time and lots of prayer.”