Constitution thumpers

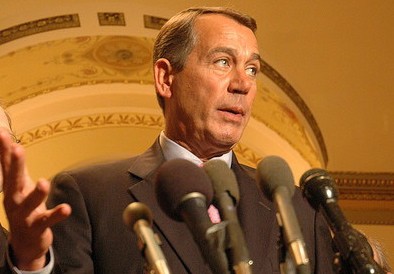

Today, U.S. Chief Justice John Roberts will swear in Rep. John Boehner (R.-Ohio) as the Speaker of the House. That's a routine gig for a Supreme Court chief justice, but yesterday's was unprecedented: on Boehner's request, Roberts also swore in the new Speaker's staff.

The staff oath began, "I do solemnly swear that I will support and defend the Constitution of the United States," and one of Boehner's aides told Politico's Richard E. Cohen that the move would "underscore our commitment to listen to the American people and honor the Constitution." He also characterized the event as private, low-key and press-free.

In other words, it wasn't a big deal and it wasn't about PR--presumably the aide just ran into Cohen on the street and happened to mention this quiet little thing Boehner's staff would have done even if no one knew about it. As Cohen points out, employment forms for House aides already include a commitment to support the Constitution. So swearing an oath is redundant.

As a PR stunt, however, it fits rights into the larger Republican narrative of being the party that, unlike some people, is committed to the Constitution. For only the third time in history, the whole document will be read in the House chamber tomorrow. And as promised this fall in its "Pledge to America," the GOP leadership plans to require that every bill "cite its specific Constitutional Authority."

Capitalization abuse and all, this is great red meat for Tea Partiers, who are constitutionally obsessed with the Constitution--or more precisely, with the ideological position that the document's main purpose is to limit congressional power. That's about all this "the Constitution is back, and it's badass" approach (Garrett Epps's phrase) amounts to, because of course laws have to be constitutional. But how to interpret the Constitution? If the document were consistently straightforward, clear and specific, then we'd have far fewer 5-4 Supreme Court decisions.

Epps observes that when the Constitution is read aloud tomorrow, almost no one will be there to hear all of it; "instead, [members] are parceling it out among themselves clause by clause" to make the most of the photo ops. All oaths aside, politicians are generally less interested in the Constitution as a whole than in individual clauses or fragments, typically those that buttress specific arguments they want to make.

In the new Congress, two diametrically opposed bills might meet the new requirement by including the same conveniently vague part of the Constitution, or they might use different, more specifically relevant snippets--much like an action alert from a religious right group and one from a religious left group might each lead with a Bible verse but make the opposite argument. When sacred text is used as message icing on a substance cake that's already baked, we learn little about the text itself.

That's okay; not every conversation needs to be about the text. But to pretend that it's the subject at hand when it isn't is just silly pandering. So is implying that we'd all be clear as to what needs to be done if only we remembered to consult chapter and verse.